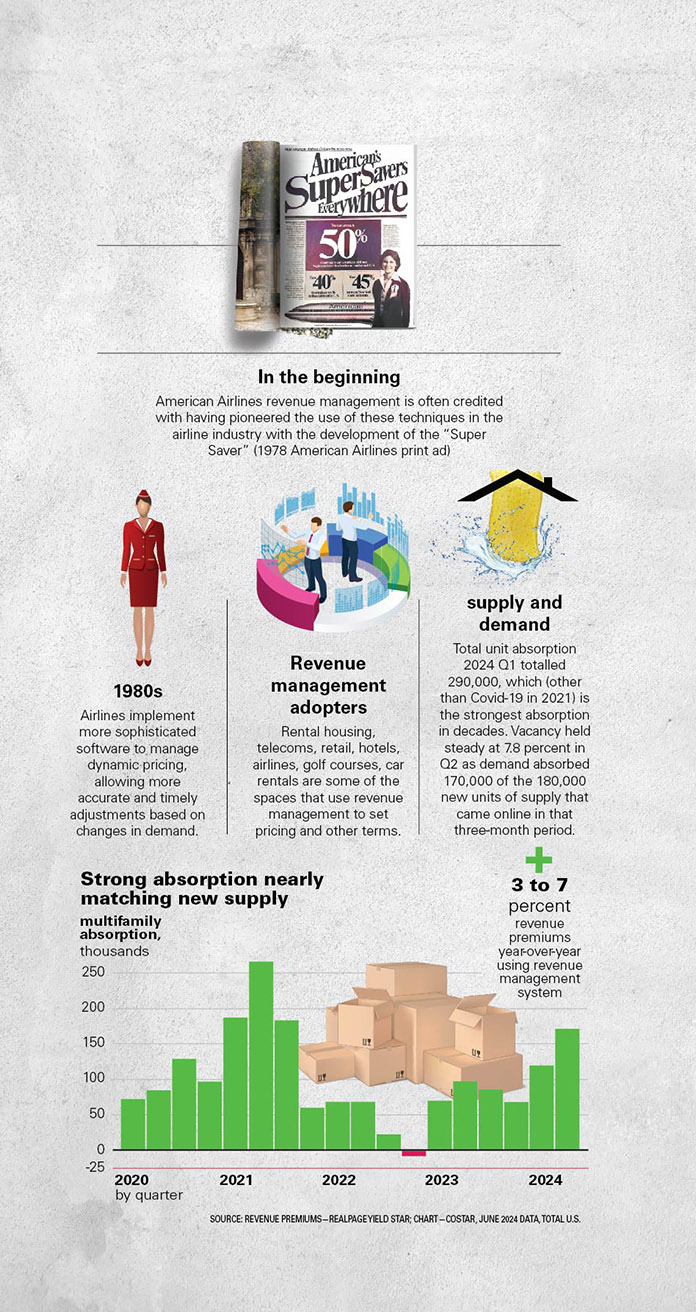

The first multifamily housing property went live on revenue management (RM) 23 years ago in February. That system was the first iteration of Lease Rent Optimizer (LRO), designed by Talus Solutions and later acquired and further developed by The Rainmaker Group in conjunction with Archstone, an apartment REIT that was purchased in 2012 by sister REITs Equity Residential and AvalonBay Communities.

Since RM systems became standard among the National Multifamily Housing Council’s (NMHC) top 50 and other large and professionally managed rental housing operators, the multifamily industry has seen higher occupancy and more stable and predictable rent growth than any time in the history of rental housing, Donald Davidoff, co-founder and CEO of Real Estate Business Analytics, Inc. (REBA) and former Sr. VP at Archstone, said in June.

“Occupancy after RM versus pre-RM is about a full point higher and users are getting better utilization of their supply. The systems react more incrementally and sooner than humans do to changes in demand.

Lastly, multiple A/B tests over several years showed LRO properties outperforming manually priced properties, so profitability has increased across the board, not just for early RM adopters,” he said.

Yet these rent recommendation tools currently are being blamed for everything from decades of rent increases, housing unaffordability, homelessness, bubbles in the multifamily investment market and even rapid inflation.

Texas-based property management software provider RealPage and California-based Yardi Systems and the clients who use their RM software are named as defendants in class-action lawsuits. The companies have drawn the additional scrutiny of the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, both of which are investigating for alleged price fixing in violation of antitrust laws. Some states are even attempting to outlaw the use of RM systems that have been trained on or use non-public competitor information, said Davidoff.

After an initial comment in its own defense, following accusatory stories in ProPublica, RealPage was silent until June 18, when it issued a statement to set the record straight.

Contrary to allegations that RealPage pressures operators to accept the recommendations of its software, RealPage explained that users decide their own rent prices and have complete discretion to accept or reject its suggestions in order to align with property-specific objectives of those using the software.

Other points made in the statement:

- Clients are never punished for declining recommendations.

- YieldStar RM never recommends that a customer withhold vacant units from the market.

- The software serves a much smaller portion of the rental market than has been falsely alleged.

- Properties using RealPage’s RM software consistently achieve vacancy rates below the national average.

The latter bullet point corresponds with the finding, based on comparison data from the U.S Census Bureau and the properties RealPage tracks, that professionally managed apartments, which are those most likely to use RM software, consistently have fewer vacancies than the broader market.

Yardi posted a similar response after a suit filed last September accused the company of violating antitrust laws with its Revenue IQ software (formerly RENT Maximizer) that is built in to Yardi’s property management programs.

Raising awareness

What can the industry do to help lawmakers and renters understand what actually drives rents and clear up misconceptions around RM?

Principal at multifamily consulting firm 20for20 Dom Beveridge, who previously held various positions at The Rainmaker Group and RealPage, responded.

“We must make legislators aware of the harmful effects of anti-RM legislation, because the intent behind them is, ‘We don’t like the sound of what the systems do, so we’re going to try and make them illegal,’ when the bills are based on a complete misunderstanding of how the technology works.”

“These laws are being written as if RM only makes rents go up, so the rationale is that if you turn RM off, rents will go down. The trouble is RM isn’t mostly what’s making rents go up and if you turned it off, rents would definitely go up further because you would completely remove the benefits that the software captures. That would mean that, on average, apartments would be less occupied and more expensive than they are now,” he said.

Rents are driven by supply and demand fluctuations. As a journalist noted in a recent Reason magazine article, landlords are in the business of maximizing profits, not rents, which, depending on market conditions, can include raising rents to meet demand or cutting rents to retain residents when demand flags.

Interest rates also drive rents—when they rise, the cost of financing increases. Add higher insurance prices, the increasing costs to maintain properties in good condition and remain compliant with regulations, along with rent control laws that make it harder to develop new properties in a nation faced with a severe housing shortage, and it’s no mystery landlords have little choice but to adjust rents upwards to maintain their investment’s viability.

No return

Despite the current issues RM is facing, no one in the multifamily industry is willing to return to the days when property managers and landlords relied on manual market research, rates of nearby properties and their own intuition to set rents, said Davidoff.

Before RM, even large owners depended on brokers to help them understand supply and demand trends, rental and vacancy rates and other economic indicators in the local markets.

While some smaller landlords still use manual spreadsheets and ledgers to determine rents, these methods are limited by available data and are difficult to scale, which can lead to longer-term vacancies from setting rents too high or leave potential income on the table from setting them too low.

Some industry pundits anticipate changes are coming to RM as a result of the scrutiny the software and its users are experiencing today and see an opportunity to fill a gap with their own products.

“Some of the largest RM providers and their clients have no choice but to reconsider how they conduct rent surveys and set market rents,” said Mark Rutzen in a piece he wrote early this year called, “What’s the problem with multifamily revenue management?”

Rutzen is co-founder and CEO of HelloData.AI, a multifamily analysis platform that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to identify similar rent and expense comps for any size apartment building in order to recommend pricing, value-adds and operational improvements aimed at maximizing NOI.

He believes transparency is being valued more highly by owners and managers and solutions that can provide the reasoning behind outputs will be favored over RM’s current “black-box” approach and opaque data sources.

“The problem isn’t the way these models work, it’s the private data they have access to. As firms seek to distance themselves from data sources that can get them sued, they’ll rely more and more on AI-driven approaches to create more transparent and fair pricing models. Models using more recent advancements in AI can now access a significantly broader range of data points on a much more frequent basis and achieve better results without relying on non-public information,” he said.

But a lack of transparency is one of the reasons Davidoff is skeptical of AI pricing solutions for multifamily housing.

“We lack the requisite volume of data for machine learning to work well, and even if it does, AI is the very definition of a ‘black box.’ Operators, rightly in my opinion, are anxious about black box solutions when they are on the line for results. It’s awfully hard for an operator to own financial results when they don’t have access to, or ability to control, pricing,” he said.

Davidoff is the designer of a new product called REBA Rent that aims to simplify the rental process and improve transparency. REBA Rent, launched last October, is touted as an all-encompassing data platform, not a point solution, that places all analytical functions, reporting, dashboards, budgeting and revenue management, on a single data model. The system does not aggregate private data.

Wrong and right

Meanwhile, Beveridge points out that, laws and litigation aside, private data’s role in multifamily RM is minimal.

“The wrong lessons are coming from those in the industry saying, ‘We need to get our data from public sources rather than private ones.’ The right lesson to learn is that it’s not about what your competitors do.

“You should use the software to make pricing decisions based on what the demand is for your property, or your unit specifically, and how much or how many units you have to sell. You’re figuring out the future supply and demand picture and that has to do with understanding things like traffic, making predictions and then understanding what your expirations are going to be over a period, because that’s what determines what your prices should be.

“If you have six different competing properties, they all have different expirations, different levels of availability and different available unit sizes. They don’t have the same demand and supply picture. We shouldn’t be saying, ‘Well, my six competitors are doing this, therefore I should do it too.’ That’s a really stupid way to make a pricing decision, which is why I think people pay too much attention to competitive pricing,” he said.

Another misconception about RM is that it only works for Class A and never for lease ups. But the portfolios of REITs like Camden Property Trust and Mid-America Apartments include both Class A and B assets.

Davidoff said, “The legacy RM systems have revenue-managed lease-ups. I myself have used them. It’s true they are a bit clunky for these uses, and therefore some RM system users have decided not to use them for lease-ups. When those systems were built, the focus was on same-store and, unfortunately, they never got around to making it easier to use on lease-ups.”

The black-box concern

While Beveridge previously explained the proper way to use competitor data in RM, Davidoff confirms that the legacy systems were designed to be dependent on competitor data.

“This made sense back then because rental housing is a fairly fungible product—one home can easily substitute for another, so competitor data can be an important metric for setting rents. Unfortunately, it turned out to be virtually impossible to collect accurate competitor rents,” said Davidoff.

Additionally, homes are not as mutually interchangeable as originally contemplated. “Location, size and unit amenity data create a larger range of rent comparisons than we expected when we initially designed and built those systems,” he said.

Because the sophisticated mathematical algorithms used by legacy RM was built by hospitality and travel people for rental housing, no one in the industry knows the actual details of how they work, said Davidoff. The result is that pricing recommendations look to most users as if they come from a black box.

This opacity of the system makes it easy for lawmakers and even operators to misunderstand how RM works, while the use of private data has opened RM software providers and their clients to scrutiny because of the misunderstanding, he said.

The courts have yet to decide the outcome of the lawsuits and some newer bills are still pending, but Davidoff thinks if any of the anti-RM bills currently being pushed through the legislature pass, based on how they are written, they would only limit the use of non-public data in recommending and setting rents.

He suggests owners who use the legacy systems educate themselves on the actual legal boundaries and not let fear create mythological boundaries.