Ed Glaeser is perhaps the pre-eminent urban economist working today, and I’ve cited his work repeatedly when looking at land-use restrictions and burdens on new development.

So I was very interested to see he’s coauthored a recent paper investigating construction productivity.

The paper essentially asks whether land-use regulation for new housing affects the productivity of construction. It finds evidence that land-use regulations are restricting construction productivity, by reducing firms’ ability to exploit economies of scale.

Stricter land-use regulations force builders to spread their efforts over a large number of relatively small projects, limiting the number of homes they’re able to build. This, in turn, limits their ability to invest in better homebuilding technology or otherwise take advantage of economies of scale.

This theory neatly ties together a lot of issues we’ve looked at previously: construction’s poor productivity record, the rise and fall of Levittown-style construction, the problem of land-use regulation, the question of why there are so few economies of scale in construction, and so on.

I think the thesis here is broadly, directionally correct. But I have issues with some of the various measures the authors use to demonstrate it, and I think their use weakens the paper’s finding.

I also think the mechanics of their model need some refinement, particularly with regards to large-volume home builders like D.R. Horton or Lennar.

More generally, I think issues of construction productivity go beyond land-use restrictions (something I doubt the authors would disagree with). Nevertheless, I think this paper sheds light on an aspect of the construction productivity problem.

History of poor productivity

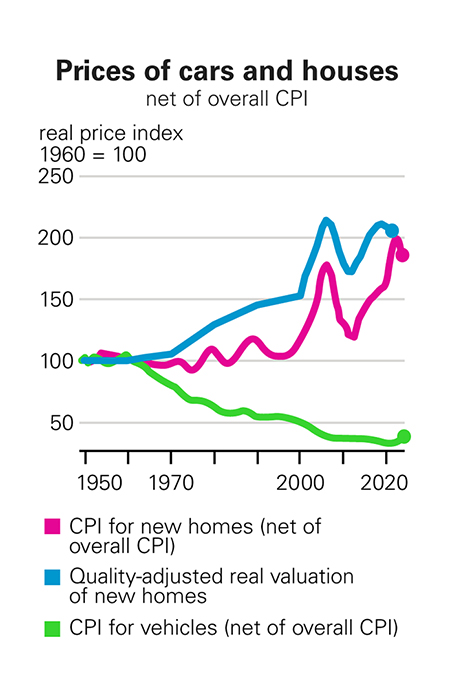

The paper starts by taking note of home building’s poor record of productivity improvement. In real terms, homes have steadily risen in cost over time, while things like cars have steadily gotten cheaper.

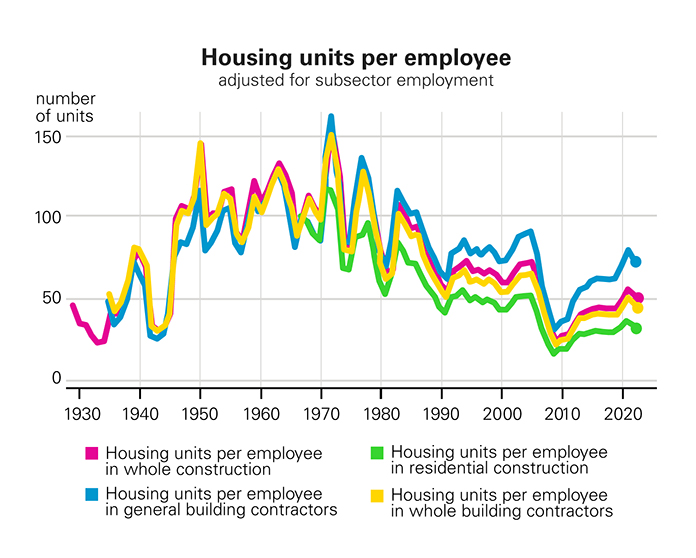

It then looks at a productivity measure—housing units produced per employee—and notes that while this improved from the 1930s to the 1960s (i.e., it took fewer and fewer workers to build a house), since then it has declined.

Today, the number of houses produced per employee is not far off what it was 90 years ago. Meanwhile, output per employee in the auto industry has increased 4x, and in manufacturing overall it has increased 10x.

Of course, I agree that construction’s record of productivity improvement has been incredibly poor, but nevertheless I have some issues here. My main one is that “housing units per employee” is an incredibly fraught measure. The data set for residential construction only goes back to approximately 1970, and before that the authors are extrapolating from employment in the entire construction sector and assuming that residential construction employment follows the same basic trend (which it does post-1970).

But even ignoring this, there are still major potential issues here: most notably, many things that would cause the number of “houses per employee” to fall have nothing to do with falling productivity.

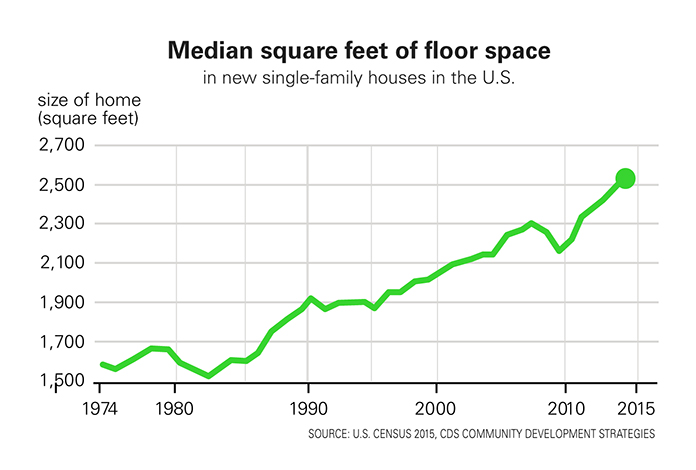

One obvious one is home size. If homes are getting larger over time, it would take more and more workers to build them, causing “houses per employee” to fall even if productivity wasn’t changing. And of course, we do see average home size increasing substantially over time.

Studies of construction productivity will often try to correct for this by using something like “square feet of home per employee” (for instance, the Goolsbee and Syverson paper we looked at a while ago used this metric), but as far as I can tell, this paper doesn’t.

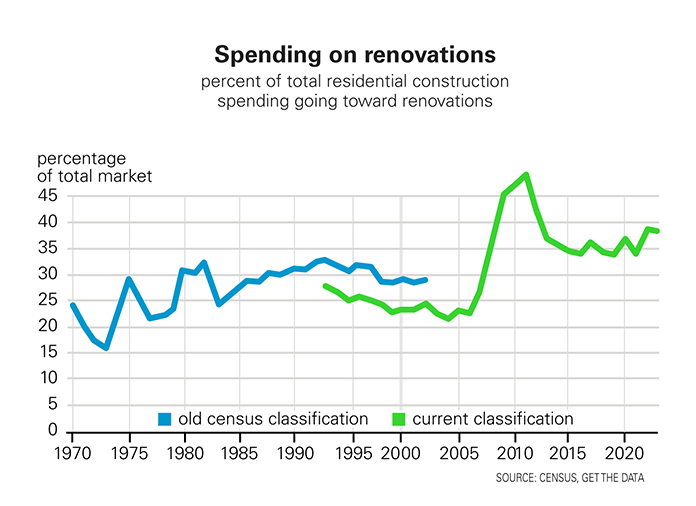

“Housing units per employee” could also fall in the absence of productivity changes if residential construction employees are doing tasks other than homebuilding, such as renovation work. And this is something we also see: renovation has become a larger and larger fraction of residential construction spending:

Finding the right metrics

So while I think construction indeed has a major productivity problem, I don’t think the measure of housing units per employee that the authors are using demonstrates this particularly well.

I’m also a bit suspect of the paper’s timing claims. The authors are painting weak construction productivity as a post-1950s issue: they note that, per their measures, prior to the 1960s productivity was improving and costs were relatively flat (though their cost time series doesn’t go back particularly far.

However, when we looked at measures of construction cost going back to before 1900, we found that, outside of a few small periods, construction costs (including housing) have basically always increased faster than overall inflation.

In some ways this is a relatively minor difference, but it does push against the idea that construction productivity is primarily a post-1950s issue of increasing land-use regulation.

From here, the paper goes on to show that land-use regulation has steadily increased since the 1950s, and also shows that a number of U.S. metros (which have high land-use regulation as measured by the Wharton Land Use Regulation Index) have exceptionally high costs compared to other cities around the world, as measured by the Turner and Townsend construction cost survey. I have no real issues here, both of these claims seem correct to me.

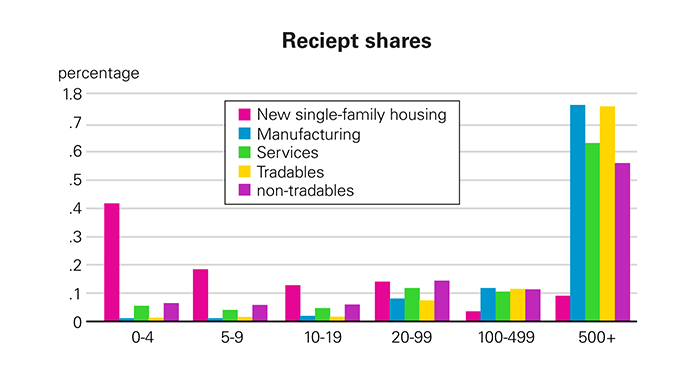

So far all this is a prelude to the heart of the paper, in which the authors try to tie these various metrics together into a theory of construction productivity based on firm size. The paper notes that construction firms tend to be very small: while in other industries, most output is produced by a small number of large firms, in home construction most output comes from firms with nine employees or less, and most homes are built by companies with fewer than 100 employees.

To account for this, the authors construct a simple model of the construction industry based on land-use regulations, management limitations, and technology.

The authors posit that a builder is limited in how many projects they can manage effectively (in the papers words, they have limited “span of control”). This means that the number of homes a builder can build is a function of project size: if projects are large, Levittown-style developments, a builder might be able to build a very large number of homes. If they’re small, with just a few homes on a site, they’ll be able to build fewer homes.

Restrictions on land use, however, make it unlikely that very large, Levittown-style developments will be approved. By forcing projects to be smaller, land-use regulation limits how many homes a builder can effectively build.

This, in turn, limits how much a builder is able to invest in new, productivity-enhancing technology, or otherwise take advantage of economies of scale. (This is a verbal description of the mathematical machinery the paper constructs for this model, which I’m not really equipped to evaluate, but the paper spells out these main implications.)

One interesting implication is that, while all industries are regulated to some degree, land-use regulations are particularly pernicious, because of how they prevent economies of scale. In other industries, regulations often act as a barrier to entry for firms, but still allow for very large firms that can produce large volumes of output cheaply.

Land-use regulations, on the other hand, make it easy for firms to enter the industry, but make it hard for those firms to build in large volumes and capture scale effects. Thus, ostensibly similar levels of regulation might have dramatically different impacts. This is relevant to our previous brief look at construction regulation, where we noted that construction isn’t obviously more regulated than other industries.

The authors then marshal some evidence for this theory. They combine data on construction firm size and output to get a measure of how output-per-employee varies with firm size, and conclude that construction firms would be far more productive if they were as large on average as firms in industries like manufacturing (exactly how much more productive depends on what you assume about the relationship between firm size and productivity).

The paper then uses the previously-mentioned Wharton Land Use Regulation Index to show that metros with higher land-use regulation (and higher construction costs) tend to have smaller construction firms, and that those firms have lower output and revenues per employee. Thus, per the authors, higher land-use regulation is driving up construction costs, and driving down productivity, through the medium of reduced economies of scale.

Conclusion

I think this is an interesting model, and in many ways it aligns with what we’ve seen previously. Land-use regulation did get much worse starting around the 1960s, and this did drive up costs and made it harder to get very large developments approved.

Very large, Levittown-style developments can take advantage of building methods, like reverse assembly lines, that much smaller projects can’t. And the large-scale builders of the 1950s do seem to have been on the forefront of adopting new technologies, like drywall and power tools.

There is also probably something to the “span of control” theory; it does take a lot of on-the-ground oversight to keep a project going smoothly, and historically it does seem to have been difficult to scale up a building operation by adding more and more projects.

In his history of merchant building, Ned Eichler notes that builders achieved success by relentlessly controlling their projects, and that scaling up required adding layers of management that made this control more difficult.

And while large builders exist today that build tens of thousands of homes a year, they seem to do so in a highly decentralized fashion, where individual markets are run as pseudo-independent operations.

But I have a few issues with the paper. First, as I’ve noted, I think some of the metrics they’re using have issues, particularly “housing units per employee.” I wasn’t able to quite follow how they calculated output per employee on a firm-by-firm basis, but if it has the same issues as the industry-wide construction, there are potentially pretty significant issues here that need buttressing.

Second, I feel like some of the basic mechanics of the model aren’t correct, or at least need more work. The model seems to explain why construction firms would tend to be small, but it doesn’t seem like it accommodates the existence of very large homebuilders like D.R. Horton, Lennar, and Pulte very well.

These builders employ thousands or tens of thousands of people and build tens of thousands of homes a year. In some ways this isn’t necessarily inconsistent with the model (as we’ve noted, in many ways these builders act like a collection of smaller builders), but it still feels like a “hole” in the theory to me, since the model doesn’t have much to say about the existence of very large builders.

(Relatedly, there’s also some potentially questionable assumptions the authors use when constructing their formal model.

For instance, they describe builders, developers, and landowners as three separate groups, but large home builders will basically be in all three of these roles. I suspect this sort of thing doesn’t really impinge on the model’s conclusions at all, but it’s worth noting.)

My final issue is that, from what I can tell, historically economies of scale in homebuilding have not primarily been an issue of land-use controls. As we noted in our look at Levitt and Sons, large-scale builders like Levitt were not necessarily any more efficient than smaller builders building just a few hundred homes per year, even in the 1950s.

I tend to think economies of scale are difficult in construction more because of the fundamental nature of construction tasks than because of land-use restrictions.

But this doesn’t mean that land-use restrictions have nothing to do with the problem, or that they’re unimportant. And I suspect the authors probably don’t disagree about any of this.

In their conclusion, they describe their model as a “back-of-the-envelope” calculation that needs significantly more development, something that can potentially shed light on it without necessarily explaining the whole thing.

In this, I think they’re correct, and I’ll continue to think about the model they’ve sketched here.

Author’s notes: I have potential reservations about the measure of land-use regulation in the Wharton Land Use Regulation Index. Some metros in the index have large jumps in how regulated they are in different versions of the index, which seems likely to be a measurement artifact, rather than actual changes in regulatory restrictions. This lowers my confidence in the index somewhat, but it’s a relatively minor issue.