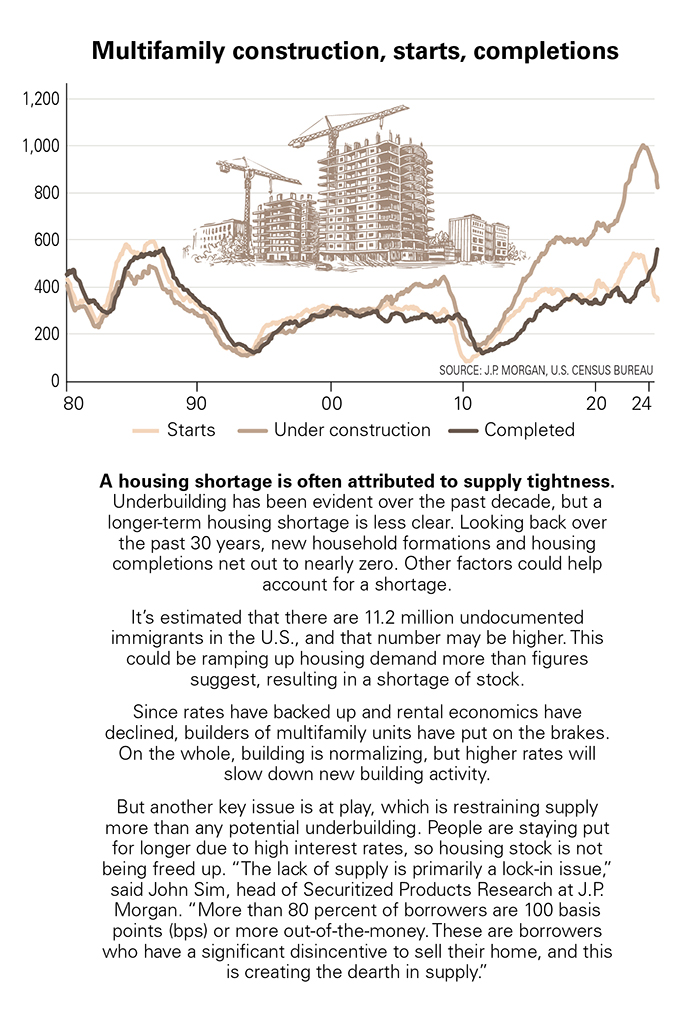

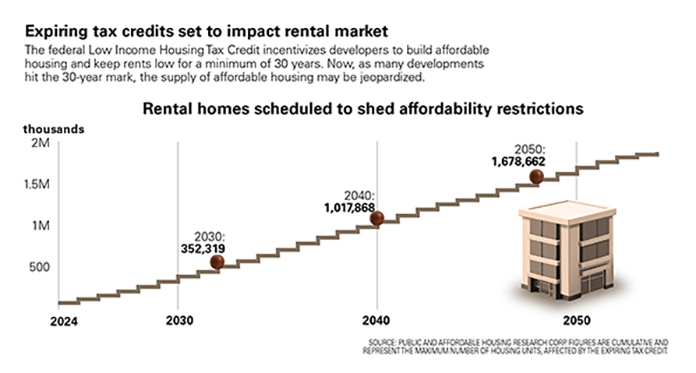

The United States is experiencing a rental housing crisis. There is a shortage of affordable housing, and many renters struggle to pay rent. Making matters worse, thousands of the nation’s affordable housing units are about to disappear as many Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) units built over the past several decades near the end of their 30-year affordability period.

Meanwhile, industry advocates at the National Low-Income Housing Coalition claim the policies put forward by the new Trump Administration do little to address the underlying causes of America’s housing crisis and make it harder for states and communities to address these challenges.

Under President Trump’s administration, the apartment sector faces potential cuts to affordable housing programs, suggesting higher costs and less available funding. However, as in any market and under any administration, opportunities still exist to drive change in a more positive direction, said Rich Larsen, CPA at Novogradac & Company LLC. The organization provides services to the affordable housing, community development, historic preservation, opportunity zones, and renewable energy fields.

The LIHTC issue

The LIHTC program is the nation’s largest and most consistent source of financing for affordable housing. So the expiration of the program’s affordability restrictions poses significant challenges for maintaining affordable housing. As the first LIHTC properties reach the end of their 30-year affordability period, property owners can choose to convert subsidized units to market-rate or sell the assets and reinvest the proceeds in other market opportunities—or they can apply for additional tax credits that establish new affordability requirements.

Moreover, a federal loophole in more than three dozen states allows property owners to convert affordable apartments to market-rate after only 15 years. This has resulted in the loss of 10,000 affordable housing units every year.

The nation lost eight percent of affordable units for extremely low-income renters during the pandemic years. And an estimated 1,075 rental properties reached the end of their LIHTC contracts last year, according to the National Housing Preservation database. That number could more than double this year to 2,269 properties. Within five years, federal assistance will have expired for more than 9,500 affordable properties with more than 337,000 rental units.

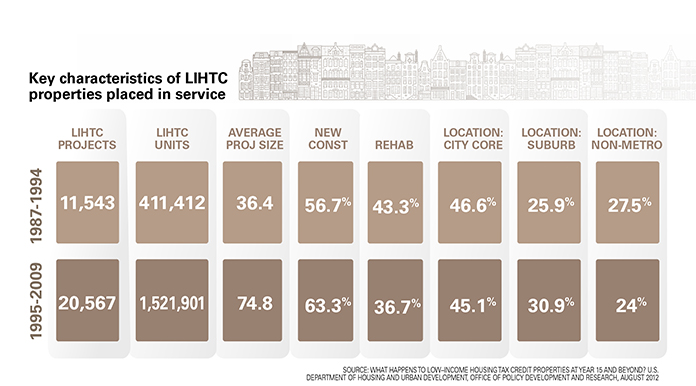

The LIHTC federal tax incentive comprises two separate funding programs—the nine-percent program covers about 70 percent of construction costs, and the four-percent program covers about 30 percent of construction costs and requires additional funding. Since its inception in 1987, it has financed approximately four million housing units, according to data from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

Some good news for the federal LIHTC may be coming this year that could enable a more efficient use of an already strained financing resource, explained Novogradac & Company founder, Michael Novogradac.

Congress will have the opportunity to change the U.S. tax code because of more than $4 trillion worth of expiring provisions from the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The LIHTC is well positioned to be included in the negotiations, especially since key provisions of the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act of 2023 sailed through the House last year with overwhelming bipartisan support as part of a broader bill.

“This would increase the amount of nine-percent credits states can allocate to finance production and preservation of affordable rental homes and lower the bond threshold for accessing the four-percent LIHTCs,” he said.

More than 25 states have applied the LIHTC model to create tax incentives that supplement the federal subsidy by extending affordability periods and filling affordable financing gaps, with more states adopting their versions each year. Although implementation can vary from state to state, their governing statutes and regulations often mirror those of the federal LIHTC.

Aging LIHTC-financed and HUD-assisted properties require more upkeep than market-rate properties.

“People sometimes forget there are two aspects to preserving affordable housing. One is preserving affordable rents. The other is preserving the physical units. These are aging 30-plus years old properties that require capital infusion, making it difficult to preserve affordability without new subsidies,” said Jay Parsons, principal and head of investment strategy and research at Madera Residential.

He said affordable investors are in a Catch-22. “If they renovate the property without tax credits, they have to raise rents to pay for it and risk being called a gentrifier. If they don’t, their rent-controlled properties age further, and they risk being called an absentee landlord,” he said.

This suggests the LIHTC preservation programs don’t go far enough highlighting one of the challenges in affordable housing as more of the original LIHTC deals age up.

“It’s why we need public-private collaboration, carrot and stick, as opposed to installing unfunded mandates that result in affordable product aging into obsolescence, as has occurred in NYC,” he said.

Interestingly, on February 12, the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development relaunched the J-51 program to help rehabilitate aging buildings and keep rents low. The revised program provides tax abatement equal to 70 percent of the residential improvements. It is available for rental projects where at least 50 percent of units are rent regulated with rents below 80 percent of the AMI or rental projects receiving substantial governmental assistance, including LIHTC.

Right timing

LIHTC owners face problems preserving affordability and taking care of deferred maintenance and other CapEx needs while keeping risk in check.

Incentivizing owners to apply for new credits at the end of an affordability period is one way to preserve affordability, but they must commit to a new compliance period.

Experts say the best time to extend affordability protections is between year 15 and year 20 after the original transaction. Most properties require renovation at this age, so the owner can come in with four percent LIHTCs and make the necessary upgrades while extending affordability protections for at least 30 to 40 more years.

This is less costly than building new affordable products because there are fewer complications to manage, said Moody’s Analytics. New builds face challenges with site location, zoning approvals, and community opposition, which can add fees and delays to a project. Obtaining new credits and restarting a compliance period while rehabbing already built properties doesn’t trigger these added constraints.

“The LIHTC program has the most meaningful impact on creating and preserving units for the lowest income cohorts, so it’s a critical piece of stock we must save,” said Alicia Hill, VP and Assistant Portfolio Manager at FCP, a privately held real estate investment company headquartered in Washington, DC., that has invested in affordable housing projects through public-private partnerships.

“Sometimes in the public sector there’s a way to get a tax exemption for an expiring LIHTC deal and commit to preserving rents similar to or aiming towards that low-income housing segment, which I define as sub-80-percent of Area Medium Income (AMI), even if it’s not at the same level that was instituted during the initial LIHTC phase,” said Hill.

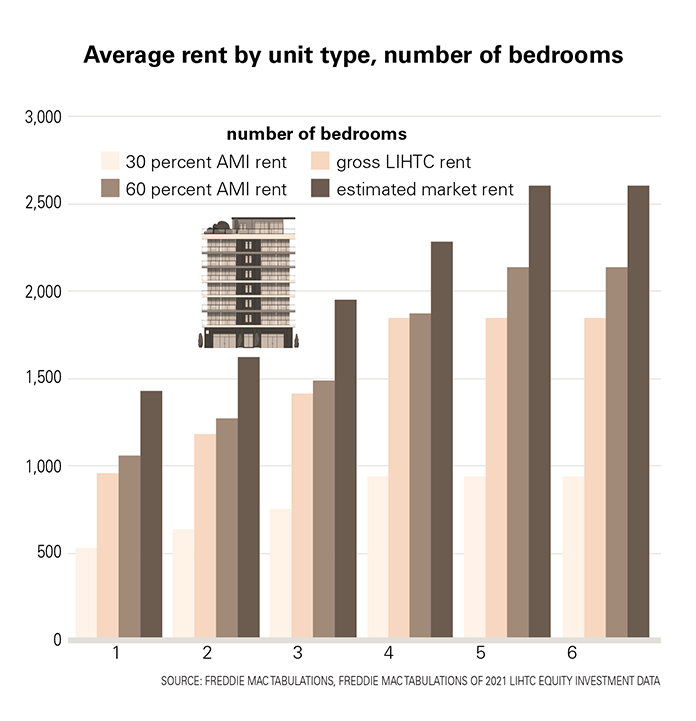

A 2022 report by Freddie Mac found that after exiting the program, units in former LIHTC properties often remain affordable to households earning 60 percent of the AMI.

While LIHTC’s income restrictions prohibit their use for moderate-income or “missing middle” housing, affordability is still a benchmark relative to location and income and doesn’t necessarily mean low income, said Hill. Many owners and developers in the conventional multifamily space are squarely within the realm of affordable housing simply because of the demographic they target.

“The markets they operate in are HUD-based, low and moderate-income, whether they choose to execute a business plan where affordability is part of the mission, investment mandate and strategy, or if it happens to be a condition of where the deal is executed or the type of customer they support. The tenant base that we ascribe to ‘Capital A’ affordable housing is often very similar to what you see in naturally occurring conventional deals of a certain age and quality condition,” said Hill.

Public-private deals explode in 2025

Certainly, the housing crisis is too big for governments to solve alone. LIHTC pundits expect public-private partnerships to expand this year as developers, nonprofits, and municipalities join forces to leverage the strengths of the two sectors to build and rehab affordable properties. HUD’s HOME Investment Partnership Program is one such program that provides grants to fund maintenance of affordable housing through public-private partnerships.

“There’s another way to reinvest capital into existing deals,” Hill said, referring to the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program and some NYC Housing Authority deals done recently around public housing with tremendously deferred maintenance issues.

Hill said some of these deals are finding success by engaging the private sector, but they are complex and don’t necessarily work in every market. Other initiatives like greenhouse gas reduction funds and transportation-oriented and historic tax credit projects can include financial commitments for affordable housing.

“These can potentially offset some of the costs or blend down the rates of the overall financing used to complete CapEx improvements for assets eligible for these funding sources, but I’ve yet to see a demonstration of how they administer all of those funds,” she said.

Much of what practitioners of public policy at the federal level need gets administrated and adjudicated at the local level, she said. So national operators aren’t necessarily going to face the same risks in one market as in another.

“It’s difficult for developers to scale their operations and commit to the affordable space if they are not incentivized to do so, especially when it’s more challenging in one location than in another,” said Hill.

Things to come

Peter Lawrence, director of public policy and government relations for Novogradac & Company, thinks the affordable housing policy community already expects cuts to affordable housing programs, especially since Trump repeatedly proposed budgets that slashed HUD funding during his first term.

“One of the key triggers for this is that Congress will need to address the nation’s debt limit,” he said.

If PHAs can’t cope with the cutbacks and generate additional revenues, affordable housing units will suffer and deteriorate as maintenance gets deferred.

But Novogradac & Company founder, Michael Novogradac, points out that the environment hasn’t been optimal for the extensive rehabilitation of affordable units for years. This has already caused a lot of PHAs to pause their RAD conversions.

Higher interest and insurance rates and just general inflation hindered PHAs in making RAD deals work. The PHAs that have made deals pencil out contributed their own equity funds to the project or utilized reserves from their state and local governments.

“And so, this is the direction where we’re pushing PHAs, because these things happen, whether there are cutbacks this year or again in five years, this is cyclical, and we want them to get out of this trap of cutbacks and struggling and trying to make ends meet,” he said.