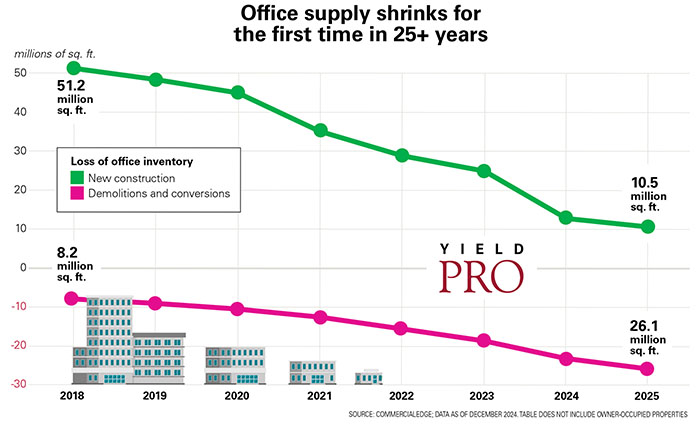

After years of empty office space casting a shadow across American cities, developers seem poised to reshape urban landscapes. For the first time in nearly three decades, office supply is on pace to shrink as developers turn to a solution percolating in developers’ minds for years: convert vacant offices into housing.

The national office vacancy rate has reached unprecedented heights, climbing to 20.4 percent by Q4 of 2024 and representing a 3.6 percent increase over pre-COVID levels five years ago. Some markets are more dire. San Francisco holds the dubious distinction of the nation’s highest office vacancy rate at 28.8 percent, while cities like Denver exceed 25 percent vacancy.

“We may now be witnessing a structural shift in some markets,” said Raphaelle Bour, lead project manager for Work Dynamics at JLL. “Many investors are now considering repurposing office buildings as a strategic capital investment.”

Construction of new office space has plummeted to historic lows, with only 9.8 million sq. ft. breaking ground in 2024—a low mark this century, according to Yardi analysts. Meanwhile, the systematic conversion and demolition of outdated office buildings now outpaces new construction for the first time since reliable records began.

“This net reduction—albeit slight—of office space across major markets likely will contribute to lowering the vacancy rate in the quarters ahead, which would benefit building owners,” said Mike Watts, CBRE Americas president of Investor Leasing. “However, the conversion trend faces a few headwinds. The pool of ideal buildings for conversion will dwindle over time. And costs for construction labor, materials and financing will remain high.”

Cities race to transform downtowns

Cities race to transform downtowns

Municipal governments have recognized that empty office buildings represent both a crisis and an opportunity. Response has been significant with cities rolling out increasingly attractive incentives to encourage office-to-residential conversions.

“Cities need to focus on making conversions feasible by removing unnecessary regulatory barriers,” said Alex Horowitz, project director of the Housing Policy Initiative at The Pew Charitable Trusts. “The U.S. is short millions of homes and office vacancy rates are at record highs. It makes all the sense in the world to convert underused commercial space into housing, but the cost per sq. ft. is just too high.”

New York City leads the charge with its 467-m program, offering up to 90 percent tax reductions for 35 years, though requiring 25 percent of units to be designated affordable. Boston’s pilot program provides 75 percent tax reductions for 29 years, while Washington D.C. has implemented a 15-year property tax freeze for office conversion projects.

“Transforming vacant offices into housing will help drive our recovery downtown while creating new homes for San Franciscans,” said San Francisco Mayor Daniel Lurie. “This is a win-win for our city thanks to the new era of collaboration at City Hall—so that we can create a thriving, 24/7 downtown that benefits both residents and business.”

Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell echoed a similar sentiment: “We must take advantage of every opportunity and tool available to create more housing options to address the issues at the root of Seattle’s affordability crisis, which impacts everyone in our city.”

“Cities experiencing particularly high commercial office vacancy rates are creating policies to remove red tape for office-to-residential conversion projects,” said Marissa Kasdan, director of research and development at KTGY. Those in the lead on this initiative include New York, Dallas and Washington, D.C. All have taken steps to encourage conversions. Modified zoning laws allow residential development in commercial zones, removal of required traffic studies and public hearing streamlines the approval process, and tax incentives tip the scale on economic feasibility.

The architectural challenges of such conversions are substantial but not insurmountable. Converting a 1970s office tower requires creative solutions that transform cubicles and conference rooms into livable apartments with proper natural light, ventilation, and privacy in each unit.

As demonstrated in successful conversion projects in Philadelphia and New York, architects must work within the constraints of existing structural columns, elevator banks, and window placement while creating functional residential layouts. The spacing of structural elements, originally designed to maximize office efficiency, must now accommodate bedrooms with adequate windows, kitchen configurations, and bathroom plumbing—a complex puzzle requiring both engineering expertise and creative space design.

Steven Paynter, principal at Gensler who has led numerous conversion projects, said that most of the “Goldilocks” office-to-residential conversion candidates are typically buildings built in the 1970s. His firm’s analysis of over 1,300 buildings revealed that only 25-30 percent make suitable candidates for conversion.

The office market’s fundamental dynamics seem to have shifted for the foreseeable future. Even as companies implement return-to-office mandates, the data suggest that hybrid work arrangements are more permanent. “While many companies are returning to the office, I expect a significantly larger percentage of the labor force will work from home indefinitely compared to pre-COVID,” said Chris Nebenzahl with real estate advisory firm John Burns Research & Consulting.

At the same time, “companies are recognizing the value in high-quality offices and premier locations, not just for recruitment and retention advantages, but also to motivate return-to-office strategies,” said Jacob Rowden, U.S. office research manager at JLL.

The office market has shown positive signs with Q1 2025 marking the fourth consecutive quarter of gains, reducing the office vacancy rate by 50 basis points from its peak. However, this modest improvement comes from a historically low baseline, and vacancy rates remain near record highs.

“The banks are going to have to dispose of that real estate,” said Richard Barkham, chief global economist at CBRE. “This will play out over two to three years. I think we’ll see a wave of offices going back to banks, and I say, they’ll be fire sold and either demolished or converted.”

Real-world success stories

Brian Steinwurtzel, co-CEO of GFP Real Estate, stands at the front line of the conversion boom. His company is currently leasing the largest office-to-residential conversion in the U.S., near the New York Stock Exchange.

“The biggest thing for us is finding a team that is experienced in doing this,” Steinwurtzel said. “We’ve assembled a team of almost a thousand people.”

His company recently completed a challenging conversion of a 1.1 million sq. ft. office building originally designed to look like an IBM punch card. “It had very few windows. It was designed to hold mostly computers. We stripped the facade and almost all of the brick off the building, added ten stories to the top of it, and drilled two light wells through it,” said Steinwurtzel.

When it comes to project selection, Steinwurtzel is pragmatic: “We will not look at a project that requires entitlements. It is just too difficult.” He focuses instead on opportunities where “B and C buildings have conversion opportunities at prices that work for us.”

“Conversions are a pathway to deliver housing in a relatively short time frame,” said Ran Eliasaf, managing partner at Northwind Group, which is behind several major conversion projects in New York.

Cities are finding that residential conversions deliver multiple benefits: reduced office oversupply, increased housing stock, and revitalized downtown cores that have become increasingly isolated from residential life.

The financial mechanics of these conversions are complex but increasingly attractive. Despite construction costs that can range from $200 to $400 per sq. ft. for a full conversion, the combination of municipal incentives, reduced land costs (the land is already owned), and strong residential demand in urban cores can create viable business models.

However, the challenges are real. “Office-to-residential conversion projects can also face financial challenges, as office rents average higher than apartment rents, nationally, on a per-sq.-ft. basis,” said Marissa Kasdan, KTGY. “Additionally, the per-sq.-ft. cost for construction to convert office to residential is typically higher than ground-up residential construction.”

For cities, the benefits extend beyond increased housing supply. Residential conversions can help stabilize property tax bases that have been eroded by declining office valuations. While converted residential properties generate less tax revenue per sq. ft. than office properties, they provide more predictable, stable income streams than vacant office buildings.

As 2025 progresses, early indicators suggest that the office-to-residential conversion trend will likely accelerate. According to CBRE data, 73 U.S. office conversion projects were completed in 2024, up from 63 in 2023, with another 309 planned or underway. RentCafe reports that a record-breaking 70,700 apartment units are set to emerge in 2025 from office conversions.

“The number of residential units added to the national inventory from conversions won’t come close to solving the national housing shortage, but it will help—especially on a local level,” said Jessica Morin, CBRE’s Americas Head of Office Research. “Meanwhile, the office market will benefit as obsolete space is removed from the market in favor of the highest and best use.”

Steinwurtzel sees the current moment as an opportunity: “We’re about halfway through it right now and it really depends on the capital stack of these buildings and where the lenders are sitting. If the lenders are ready to clear at the market price there’ll be a lot of conversions.” He adds that this window has an end date: “I think this is a moment in time. It won’t last forever. We’re trying to take advantage of that moment.”

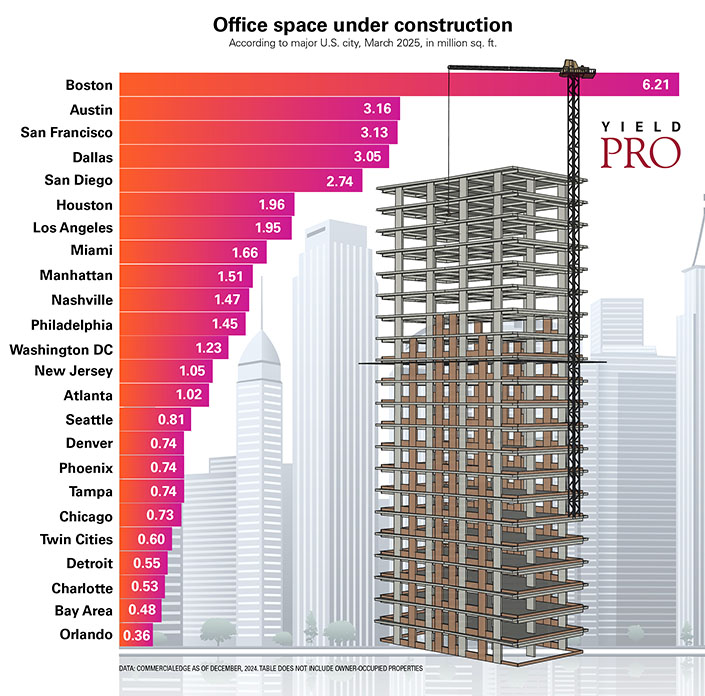

“Atlanta, Denver, Phoenix, the San Francisco Bay Area and Seattle have all been identified by a 2024 Urban Institute study as prime candidates to benefit most from such conversions,” said Kasdan.

The transformation of urban office districts into mixed-use neighborhoods represents more than just a response to market pressures—it reflects a fundamental evolution in how Americans think about urban living and working. The rigid separation between commercial and residential districts that characterized 20th-century urban planning is giving way to more integrated, walkable communities where people can live, work and socialize within the same neighborhood.

This shift carries profound implications for urban sustainability and quality of life. Shorter commutes, reduced automobile dependence, and more diverse neighborhood economies all contribute to the environmental and social benefits of mixed-use development. As more office buildings transform into apartments and condominiums, downtowns that once emptied out after business hours are evolving into 24-hour communities with the added vitality of residential life.

The historic contraction in office supply represents an ending and a beginning. While it marks the conclusion of an era of speculative office construction that often outpaced actual demand, it also signals the start of a more sustainable approach to urban development—one that prioritizes flexibility, behavioral patterns, and the adaptive reuse of existing resources. As developers work through office-oversupply, their solutions are quietly reshaping American cities in ways that may prove more lasting and beneficial.

For urban dwellers and city planners alike, the great office conversion offers a glimpse of what post-pandemic cities might become: more residential, more diverse, and ultimately more human in scale and function.

Empty towers, once snapshots of urban distress, are proving that even the most challenging real estate crises can become new horizons of American ingenuity.