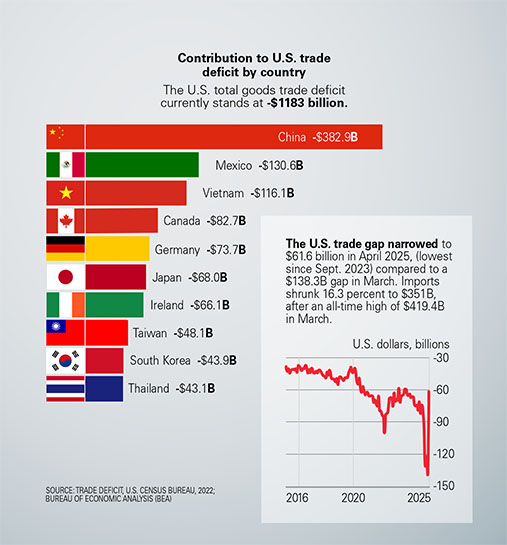

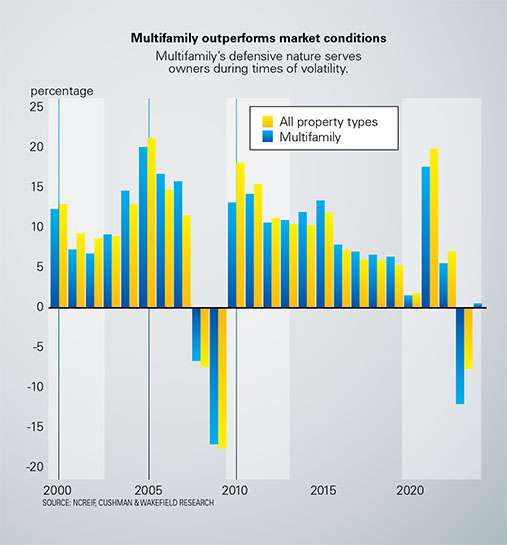

The multifamily sector has shown remarkable resilience in recent years, enduring interest rate shocks, inflation, and regulatory shifts. Now it faces a new challenge: tariff headwinds that could further inflate operating and development costs. In May, the Trump administration announced sweeping new tariffs on a range of Chinese imports, including steel and aluminum—critical materials for construction. Though most hikes won’t take effect until 2026, the policy is already unsettling markets.

Chinese steel and aluminum tariffs are set to jump to 25 percent and 50 percent, respectively. Even though much of U.S. multifamily construction relies on domestic or North American sources, global commodity markets react as a whole and push up prices across the board as demand shifts away from China.

Adding to the turmoil, in June, a federal court struck down Trump’s reciprocal tariff authority, citing executive overreach. While a temporary stay keeps tariffs in place for now, the decision introduces fresh uncertainty, complicating planning across the development pipeline.

Already, the industry faces volatile material pricing, fragile supply chains, and risk-averse lenders. Fixed-price contracts are harder to secure, and capital deployment has slowed. With no clear policy direction and rising costs, the multifamily sector is navigating a landscape where strategic agility is more essential than ever.

Raising capital in this environment is difficult even for the biggest players. Institutional investors who once had little trouble securing funding, are now facing headwinds. “Even the brand names are knocking on five times more doors just to raise half as much capital as before,” said rental housing economist Jay Parsons.

This sluggishness isn’t rooted in weak fundamentals—demand for rental housing remains solid—but in the capital structure of the market itself. Parsons notes that many limited partners are currently tied up in existing commitments. With liquidity constrained, they’re reluctant to commit fresh capital until they see distributions or asset sales materialize.

“But selling is difficult when valuations haven’t recovered and interest rates remain elevated. There’s a lot of capital waiting to be recycled,” Parsons explained. “Investors want to see realized returns before they re-up, but that’s tough in a market where buyers are cautious and values are still depressed.”

Alicia Miller-Yoder, Head of U.S. Capital Markets for Denver-based Black Salmon Capital, said today’s capital-raising environment is the most difficult she’s seen in her 12-year career.

“Liquidity is tight, and there’s a real sense of hesitation,” she said, citing persistent high interest rates, limited exit options, and tariff-related uncertainty that make it harder to underwrite deals with confidence.

She adds that some capital is sitting on the sidelines, waiting for a 2008-style reset that may never come. “We could even see bailouts for some large institutions that overextended during the last cycle. That means the distressed deals people are waiting for may never hit the market in a meaningful way.”

For developers already stretched by higher interest rates and elevated labor costs, tariff ambiguity may be the final straw. A few developers are simply walking away from deals. The effect is pronounced in high-growth Sun Belt metros like Austin, Phoenix, and Nashville, where softening rent fundamentals and an influx of new supply are making new starts harder to pencil out.

But savvy long-term players are finding ways to stay active by identifying alternate supply chains, shifting development activity to lower-cost markets, or leaning into renovation over ground-up construction. Others are capitalizing on pockets of opportunity by shifting toward operational efficiency and capital improvements.

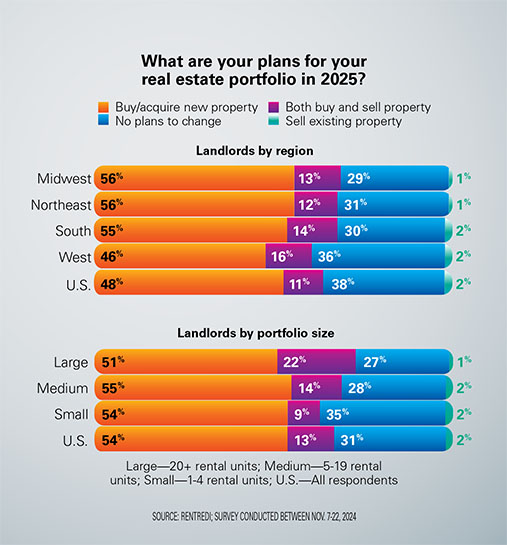

A recent survey conducted by RentRedi found that nearly 60 percent of landlords plan to expand their portfolios in 2025, with significant investments earmarked for property upgrades. This proactive approach suggests confidence in the long-term fundamentals of the multifamily sector, despite near-term uncertainty.

Material concerns

The materials challenge isn’t confined to ground-up developers. Operators managing large portfolios face the same volatility. Many of the materials relied on in property operations—from plumbing parts to flooring to light fixtures—aren’t made in the U.S. They’re imported from countries like China, Taiwan, and others, explains Rob Beardsley co-founder of Lone Star Capital.

“That means supply disruptions or tariffs in any of those countries ripple directly into maintenance budgets. When tariffs go up, so do costs. And, while no one can perfectly predict how long these trade conditions will last, savvy operators stay aware of where their materials are coming from and how to budget for volatility,” he said.

It’s not just about local vendors—it’s about global logistics. Successful operators are reassessing sourcing strategies, exploring alternative supply chains, and even stockpiling essentials where feasible. This kind of proactive thinking separates resilient firms from reactive ones.

Miller-Yoder highlights another key stress point: stalled exits in the secondaries market. “There’s a disconnect between what investors were promised and what the market is delivering. That misalignment breeds hesitation,” she said.

“But perhaps the most under-discussed issue is a broader reluctance to adjust to the new market environment,” she added, especially among investors still looking for value-add deals at yesterday’s cap rates.

“The value-add multifamily strategy performed phenomenally well in the years following the Global Financial Crisis. Those who got in early saw massive gains. As a result, a lot of capital still believes in the playbook that worked then: buy underperforming assets, renovate, and raise rents. But today’s market is fundamentally different,” said Miller-Yoder.

Cap rates remain compressed relative to borrowing costs, and many value-add assumptions from 2021–22 haven’t panned out. “The post-COVID years were an anomaly—fueled by low rates, rapid recovery, and stimulus. Investors need to recalibrate because waiting for the old market to return might mean missing today’s opportunities,” she said.

Black Salmon Capital is targeting Class A properties in high-growth markets like Miami and St. Petersburg, Florida—favoring newer assets in prime locations.

A contrarian view

But Sam Tenenbaum, head of Cushman & Wakefield’s Multifamily Insights, said the value-add space is worth watching, especially for those looking to go where the herd isn’t.

He noted a clear trend emerging at recent industry events where most institutional investors like Black Salmon Capital still prefer Class A or assets built within the past 90 days. “They are easier to manage and tend to attract tenants with more disposable income. In today’s inflationary environment, that segment of renters is less price-sensitive and more stable,” he said.

But the concentration of capital at the top end of the market has consequences.

“When everyone is chasing the same type of asset, pricing firms up quickly. While fundamentals still matter, capital flows can distort pricing and compress returns. In contrast, the B-minus and C-class space—particularly 1970s- and 1980s-era properties—has seen far less investor attention recently,” he said.

Ironically, these older properties were hot targets during the pandemic boom, with syndicated capital paying peak prices under aggressive assumptions and minimal operational experience. As Miller-Yoder explained, much of that capital is now stuck in underperforming, distressed deals—prompting a market retreat, and, as Tenenbaum sees it, opening the door for experienced operators.

“While these older buildings often need CapEx and hands-on management, they are naturally occurring affordable housing and tend to sit in markets and neighborhoods with solid fundamentals. And the discount relative to newer assets can be stark, offering cap rates north of six percent in select secondary markets, which is an increasingly rare sight in multifamily today,” said Tenenbaum.

“If your outlook aligns with a ‘higher for longer’ interest rate environment, then your returns will have to come from yield and operational upside. But that’s where Class B shines,” he said.

To remain competitive, developers, operators and investors alike must shift their perspective. The global nature of construction and maintenance means what happens thousands of miles away can hit your profit and loss at home. Whether tariffs are a long-term reality or a temporary political maneuver, their impact is being felt today.

The smart move

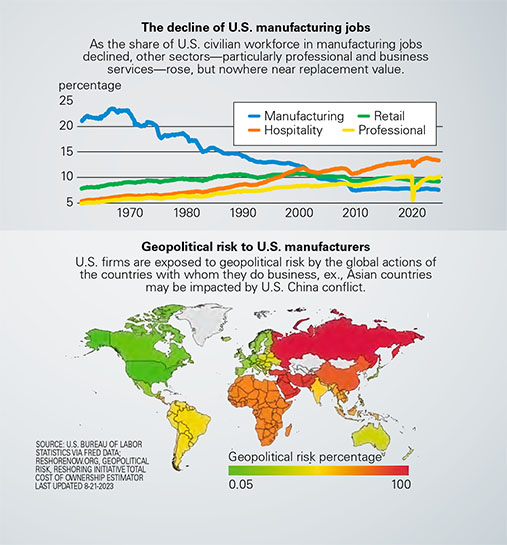

As Trump continues his long-term plan to bring manufacturing back home to the USA, a strategy that will take years, tariffs will continue to be a drag on the economy. Hardest hit will be small firms already operating on the margins.

The multifamily industry is largely supportive of the president’s efforts to increase domestic manufacturing activity. But in the National Multifamily Housing Council’s March 2025 Quarterly Survey of Construction & Development Activity, 75 percent of respondents reported repricing their deals with an average four percent increase.

Yet, despite these headwinds, Alexander Szikla, Advisor Director of Real Estate at Argo Capital Advisors thinks the tariffs will provide potential opportunities for real estate investors in the multifamily sector. He also sees a potential rebound in the market later this year.

With new multifamily permits having dropped 20 percent in 2024 and completions expected to fall another 15 percent in 2025, this supply slowdown is projected to push rents higher, especially in high-demand markets like Atlanta, Phoenix, and Dallas, he said on his LinkedIn page.

“Many major multifamily markets should see positive rent growth and stable vacancy rates by mid-year, with only a few laggard markets taking longer to recover,” he added. The multifamily sector’s long-term trajectory remains sound for those prepared to navigate the turbulence with discipline, creativity, and vision.

Ultimately, the firms that thrive in this next chapter will be those that can integrate geopolitical awareness into their operational and investment strategies. According to industry insiders, that means tracking trade policy as closely as rent comps. It also means knowing when to pivot—whether that’s rethinking a pipeline deal, renegotiating vendor contracts, or accelerating a capital improvement project before cost inflation worsens.

Dave Meyer, real estate investor and VP of data and analytics at BiggerPockets said he has shifted his focus toward safety and smart positioning. He is raising his cash reserves, culling underperforming assets and tightening his real estate criteria.

“Markets go through cycles and the best investors don’t get caught up in euphoria or fear. They adapt. They manage risk. They prepare for different outcomes,” Meyer said.

“If you’re feeling uncertain, that’s not a bad thing. It means you’re paying attention. The worst thing you can do right now is assume that everything will work itself out. The smarter move is to stay cautious, stay diversified and focus on building long-term resilience.”

“That’s how I’m playing it. And I think more investors should consider doing the same,” Meyer said.