The American apartment market in 2025 is a paradox: a landscape of gleaming new towers and persistent shortages, of record construction and deepening affordability crises. As the nation grapples with demographic shifts, economic uncertainty, and evolving housing needs, the voices of industry professionals illuminate both the challenges and the road ahead.

Building boom—but not for everyone

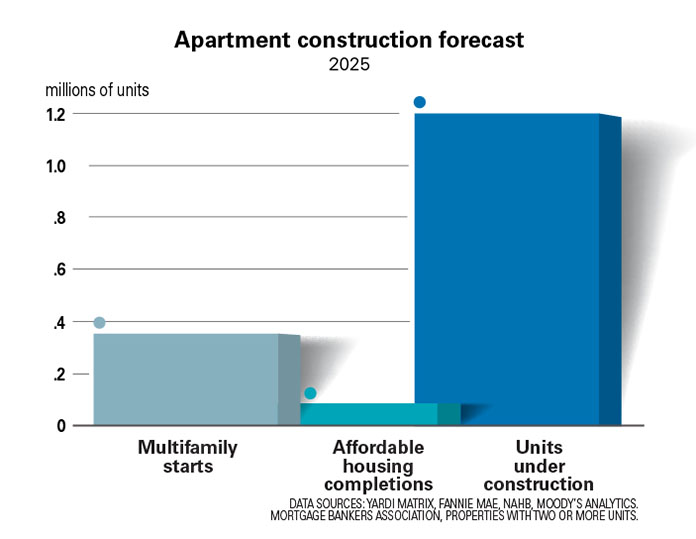

The numbers are impressive: more than 460,000 new apartments delivered in 2024, with another half-million expected in 2025. Yet, this boom masks a troubling reality.

“We’re building more apartments than at any time in the last fifty years,” said Doug Bibby, former president of the National Multifamily Housing Council. “But the vast majority are luxury units, not the workforce or affordable housing that’s so desperately needed.”

Indeed, nearly 89 percent of new apartments are high-end, targeting affluent renters in urban cores and fast-growing Sunbelt cities. “Developers follow the money,” explains Kimberly Byrum, managing principal at Zonda Advisory. “With construction costs and land prices so high, it’s almost impossible to make the numbers work for affordable projects without significant subsidies.”

The result? A shrinking supply of affordable apartments. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, the U.S. lost 4.7 million affordable units between 2015 and 2020. “We’re losing affordable units faster than we can build them,” warns Diane Yentel, president of the coalition. “It’s a crisis that’s hitting families in every state.”

Demand outpaces supply—again

Despite the construction surge, demand continues to outstrip supply. In early 2025, annual absorption topped 700,000 units—an 18.5 percent surplus over completions. “We’re seeing unprecedented demand, especially among young adults forming new households,” said rental housing economist Jay Parsons. “But with construction starts slowing, the gap could widen again soon.”

Rising interest rates, labor shortages, and higher material costs are all taking a toll. “It’s a perfect storm,” said Laurie Baker, CEO of Camden Property Trust. “Financing is tougher to secure, and every project faces more hurdles than it did just a few years ago.”

If these trends persist, rents could surge once more. “We’re already seeing upward pressure in markets where new supply is tapering off,” Parsons adds.

The affordability crisis

Perhaps the most urgent challenge is affordability. The country faces a shortage of 7.3 million affordable rentals, with just 34 available units for every 100 extremely low-income renter households. “The affordable housing crisis is the civil rights issue of our time,” said Chrystal Kornegay, executive director of MassHousing. “We need bold action at every level—federal, state, and local.”

While 2025 will see a multi-year high of 78,000 new affordable units, it’s not enough. “We’re barely scratching the surface,” said Michael Novogradac, managing partner at Novogradac & Company, which tracks affordable housing finance. “Rising costs mean each dollar of subsidy builds fewer units, and the pipeline is shrinking.”

The aging rental stock compounds the problem. “The median apartment in the U.S. is over 40 years old,” said Paula Cino, vice president at the National Multifamily Housing Council. “We need billions for repairs and upgrades, and many older buildings are at risk of being lost entirely.”

Regional disparities and the “missing middle”

Not all markets are equal. Cities like Austin, Raleigh, and Phoenix have seen a flood of new supply and even falling rents. “Austin is a unique case,” said Charles Heimsath, president of Capitol Market Research. “We’ve delivered so many new units that rents have actually dropped by nearly 10 percent in some neighborhoods.”

But most of the country isn’t so lucky. “Two-thirds of new construction is clustered in just 20 metros,” said Nancy Packes, principal of Nancy Packes Data Services. “Smaller cities and rural areas are being left behind.”

The “missing middle”—housing affordable to moderate-income families but not subsidized—remains elusive. “It’s the hardest product to build,” said David Schwartz, CEO of Waterton. “Luxury units pencil out because rents are high, and affordable units need subsidies. The middle gets squeezed.”

Single-family vs. multifamily rentals

Another trend is the divergence between single-family and multifamily rentals. “Single-family rents have surged by over 40 percent since the pandemic,” said Daryl Fairweather, chief economist at Redfin. “People want more space, and there just aren’t enough homes to go around.”

In January 2025, the average rent for a single-family home was $2,179, compared to $1,820 for a multifamily unit. “The multifamily boom has helped stabilize apartment rents,” said Greg Willett, chief economist at LeaseLock. “But single-family rentals are still expensive and in short supply.”

Smaller apartments, higher rents

Smaller apartments, higher rents

As demand has soared and land prices have climbed, the average size of new apartments has shrunk. “Developers are building more studios and one-bedrooms to maximize returns,” said Jessica Morin, director of U.S. Office research at CBRE. “The typical new apartment is under 900 sq. ft., and families are finding it harder to find larger units.”

For many renters, this means paying more for less space. “It’s a squeeze, especially for families,” Morin adds. “The market is catering to singles and couples, not households with kids.”

To meet projected demand and address the existing deficit, the U.S. needs to build 4.3 million new apartments by 2035, including 600,000 to make up for past underbuilding. “It’s a huge challenge,” said Ryan Davis, chief economist at Witten Advisors. “We need more construction, more preservation, and more innovation.”

The industry is not without its obstacles.

Rising costs: “Construction costs are up 30 percent since 2019,” said Ken Simonson, chief economist at the Associated General Contractors of America. “It’s making projects harder to pencil out.”

Financing and policy: “Higher interest rates have made financing much more difficult,” said Jeff Adler, vice president at Yardi Matrix. “Affordable projects are especially hard to get off the ground.”

Regulatory barriers: “Zoning and permitting delays are a huge issue,” said Emily Hamilton, senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center. “We need to reform local policies to allow more housing.”

Aging stock: “We’re at risk of losing hundreds of thousands of affordable units unless we invest in preservation,” warns Yentel.

Insurance risks: “Natural disasters are destroying thousands of homes each year,” said Sarah Saadian, senior vice president at the National Low Income Housing Coalition. “We need to build resilient, sustainable apartments.”

Despite these challenges, there are reasons for hope. “The construction boom has provided some relief in select markets,” said Jay Parsons. “And there’s growing recognition that we need to prioritize affordability and workforce housing.”

Innovations in modular construction, adaptive reuse, and public-private partnerships offer potential solutions. “We’re seeing more creativity than ever before,” said Byrum. “But we need policy support to scale these ideas.”

At a crossroads

The state of apartments in the U.S. in 2025 is a study in contrasts. On one hand, the nation is building more apartments than it has in decades, and renters in some markets are seeing more choices and even lower rents. On the other, millions remain priced out, and the supply of affordable housing continues to shrink.

“The challenge for the years ahead is clear,” said Doug Bibby. “We need to build not just more apartments, but the right kinds of apartments, in the right places, and at prices Americans can afford.”

Only then can the U.S. hope to close the gap between abundance and scarcity, and ensure that the promise of a safe, affordable home is within reach for all.