Voters in California rejected a measure on November 3, 2020, that would have overturned a hard-fought compromise over rent control in one of the most expensive rental housing markets in the nation.

Proposition 21 would have given local lawmakers in cities like Los Angeles and San Francisco the ability to create tough new rent controls on many rental apartments, single-family rental houses and rental condominiums.

California already has one of the strongest statewide rent control laws in the U.S. Lawmakers passed the law in 2019, in response to quickly-rising rents. Lawmakers in New York City, Washington, D.C. and Oregon also passed tough new rent control laws in 2019. It was one of the biggest years for new rent control laws in a long time.

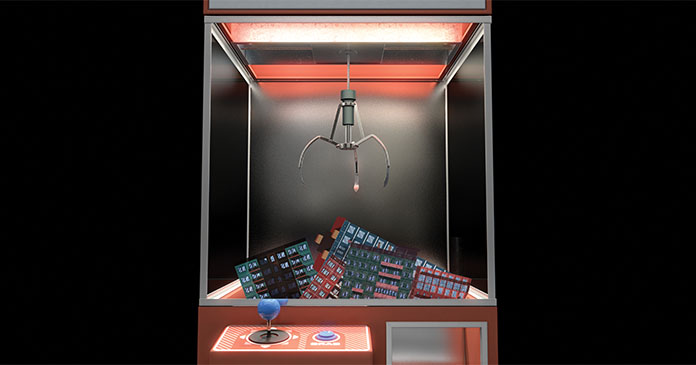

Apartment investors worry that the laws passed in 2019 are just the beginning. Most states in the U.S.—including California—have statutes that prevent local cities and towns from passing their own tough, new rent control laws. Proposals like California’s Proposition 21 would chip away at these state laws—opening the floodgates to new rental legislation.

“You are going to see a lot of battles in states over rent control,” says Alex Rossello, manager of public policy for the National Apartment Association, based in Washington, D.C.

Pandemic brings lower rents to many apartment markets

The economic chaos caused by the coronavirus has drawn attention to the plight of low-income renters and the high cost of housing. At the end of 2020, the advocates for renters focused on extending moratoriums on evictions and demanding that Congress provide rental subsidies for millions of renters who have lost jobs during the pandemic.

“Rent control laws become less relevant in a downturn,” says Barbara Byrne Denham, senior economist for Reis, Inc. a real estate data firm based in New York City. “In the current downturn, there is no upward pressure on rents.”

Rents were falling in many apartment markets in the last months of 2020. The metro areas where rents rose 2020 were largely smaller metros, often in Midwestern states that have not been the places where rent control laws have typically flourished, according to Denham.

“We expect further rent declines in 2021 in most markets—though the apartment market will suffer less distress than office and retail,” says Denham.

However, industry advocates worry that a growing willingness to “cancel rent” will turn into a greater willingness to pass new rent control laws once apartment rents begin to grow again.

Lawmakers in many cities seem very willing to call for and, if possible, create and extend moratoriums on evictions. These measures can protect renters from eviction for a time, but they do nothing to help property managers who may fall behind in paying expenses needed to safely operate a building. Those costs include utilities, property taxes and the cost of their own mortgage on the building.

“We think that we will see more efforts to pass rent control across the country in 2021,” says Jim Lapides, vice president with the National Multifamily Housing Council (NMHC), based in Washington, D.C.

Voters reject new rent control in California

Voters in California rejected Proposition 21, the recent ballot initiative, by a wide margin. Only 40.2 percent voted in favor compared to 59.8 percent against.

The ballot initiative would have chipped away at the Costa Hawkins Rental Housing Act of 1995, California’s state law that keeps local governments from adding to existing rent control laws on older apartments built before 1995—which are already subject to rent control laws in cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles.

California state lawmakers turned Costa Hawkins on its head in 2019. They created a statewide law that is one of the strongest rent control statute in the U.S. Under California’s new rent control law, landlords cannot raise rents on existent tenants more than 5 percent plus the current rate of inflation in a given year at most apartments that are more than 15 years old.

Advocates for renters immediately began collecting signatures to get Proposition 21 on the ballot after the defeat of a similar measure, Proposition 10, in 2018. However, even Proposition 21 kept some restrictions on what local governments could do. New rent control laws could not apply to apartments less than 15 years old, for example, preserving some incentive for new development. New rent controls could apply to single-family rental houses, but not if the landlord owned only one or two rental units.

The case for and against rent control

Advocates for renters say that rent control laws make it possible for low-income renters to continue to live in cities where the rents are already often sky-high. Rent control laws can also protect residents from rents that rapidly rise when neighborhoods change through gentrification.

Advocates for the apartment industry say developers have less incentive to build new apartments in places with tough rent control laws—often places like San Francisco where it is already difficult and expensive to build.

“California’s voters have clearly spoken,” says Greg Brown, senior vice president for the National Apartment Association. “Californians have recognized that while rent control policies may be politically popular, they would do nothing but exacerbate the state’s severe housing challenges.”

For example, in Oregon lawmakers created a rental control law in 2019 that limits the increase in apartment rents to 7 percent per year plus inflation. Even a limit like this could cut into the number of new apartments built by developers, according to a report by NAA and Capitol Policy Analytics, based in New York City.

Under normal conditions, rising rent levels motivate developers to build more rental apartments. A sudden spike in rents would motivate faster action by developers to build new apartments, according to industry advocates.

Rent controls cut into that incentive. If the city of Seattle passed a cap on rental increases similar to the one passed by Oregon, developers would probably build 1,739 fewer new rental apartments per year, according to the NAA report. A similar hypothetical local rent control law would result in 779 fewer units constructed annually in Denver, 320 fewer per year in Chicago and 233 in Portland, according to the report.

However, in the most expensive cities in the U.S., the high cost of housing continues to draw developers—even in the chaos caused by the pandemic. Many of these most expensive cities are the same places where rent control laws got tougher in 2019.

Despite California’s tough new rent control law—and worry that renters were fleeing big cities (see The world didn’t end—developers keep building story)—developers started construction on $2.0 billion in new apartment projects in Los Angeles in the first three quarters of 2020, according to Real Capital Analytics. That makes L.A. the place where developers spent more to start new apartment projects, by dollar volume, than any other metro area in the U.S.

In San Francisco, which is also subject to California’s new rent control law, developers started construction on apartment projects totaling $1.9 billion—making San Francisco the second biggest city in the U.S. for new apartment construction, by dollar volume, in the first three quarters of 2020.

New York City came in third, with $1.3 billion, despite New York State’s tough new rent stabilization law, also passed in 2019. In the Washington D.C. metro area, which also has an existing rent control law in D.C., developers spent $1.3 billion to start construction on new apartment projects, the fourth largest dollar amount in the U.S.

All of these cities have a long, tortured history with rent control laws that were often created decades ago in the supposedly temporary housing crisis after the Second World War. The housing crisis never ended in any of these cities. New construction of rental apartments largely ground to a halt in these places for decades afterward.

Rent control laws were not the only reason that market-rate apartment developers stopped building in places like the South Bronx or Southeast Washington, D.C., but advocates for the apartment industry believe rent control laws played a supporting role.

Few new rent control proposals in the works

In most parts of the country, state laws passed in the 1990s make it impossible for local governments to pass new rent control laws. Just five states—California, New York, New Jersey, Maryland and Oregon—and the District of Columbia have cities with some form of residential rent control law.

Most of the other states in the union have some kind of state law to make it illegal for local lawmakers in a city or town to pass new laws that restrict the ability of landlords to raise rents.

In Seattle, for example, local lawmakers would love to be able to pass a local rent control law for the city, says NAA’s Rossello. But a Washington State statute prevents them.

Republican lawmakers, who tend to oppose rent control legislation, also continue to control the legislatures of many states. The 2020 election did little to change that. Efforts by Democrats to gain seats failed in many parts of the U.S., and Republicans gained control of the statehouse in states like New Hampshire.

“You are going to see a lot of status quo because of this,” says Rossello.

However, in states like Washington, Colorado and Massachusetts, lawmakers are still eager to pass more laws to protect renters from price increases.

“There are a number of bills introduced in previously statehouse sessions that haven’t made it over the line to be passed into law,” says Rossello. “Renter advocates in those states are highly motivated to get those through.”

Eviction moratoriums and rent control tangle in New York City

In New York City, the chaos caused by the coronavirus has worried both rental housing advocates and the owners and managers of the city’s older apartments, many of which of subject to New York State’s rent stabilization laws. Those laws were toughened in 2019, and keep the rents for hundreds of thousands of apartments priced well below the market rate.

Millions across the U.S. have lost jobs in the pandemic, including many low-income New Yorkers who had worked in businesses like hotels and restaurants especially hurt in the pandemic. Eviction moratoriums have kept many of these people from being evicted, even as millions fall behind in their rental payments. However, these moratoriums will eventually expire. The unpaid rent will have to be paid, or these renters will eventually face eviction.

“The burden of unpaid rent just builds up,” says Rossello. Some of these rent stabilized apartments in New York City are owned by investors who manage thousands of units. Others are smaller owners who are less able to manage with missed rent. “Operators have all kinds of expenses that they have to pay, like property taxes.”

New York’s rent stabilization laws add complexity. Before the laws were strengthened in 2019, property owners had used a variety of methods allowed under the old law to raise the rents more than the small increases allowed by rent stabilization. Some landlords also harassed tenants to get them to move out, according to New York State prosecutors who brought several cases against New York City landlords.

The new, tougher rent control law put an end to all that by making it much more difficult to raise the rents on tenants. “New York’s expanded rent control law, which passed in 2019, protected a number of tenants and the de-controlling of units stopped,” says Denham.

There is a worry that some landlords might use the crisis caused by the pandemic to evict tenants who have fallen behind in their rent. “This is why a number of cities have passed temporary pandemic-induced non-eviction provisions, or moratoriums,” says Denham.

Author Bendix Anderson