Something huge happened in 1971. And both Edward Snowden and Jack Dorsey are asking the same question.

In mid-August, Twitter Founder and CEO Jack Dorsey tweeted a strange hashtag: #WTFHappenedin1971.

A few weeks later, Edward Snowden, the CIA subcontractor turned whistleblower who revealed the NSA’s unlawful mass surveillance program, shared a similar post.

It’s unclear if Dorsey and Snowden have similar ideological views, but it’s clear both men are seeking answers to the same question (or prompting others to look themselves): what in the world happened in 1971?

When everything changed

For those who aren’t aware, there is an entire website dedicated to that question: wtfhappenedin1971.com.

The first thing that becomes apparent is that something happened in 1971. This fact is made clear by a series of charts, all based on government data, that show various odd economic trends began in that year.

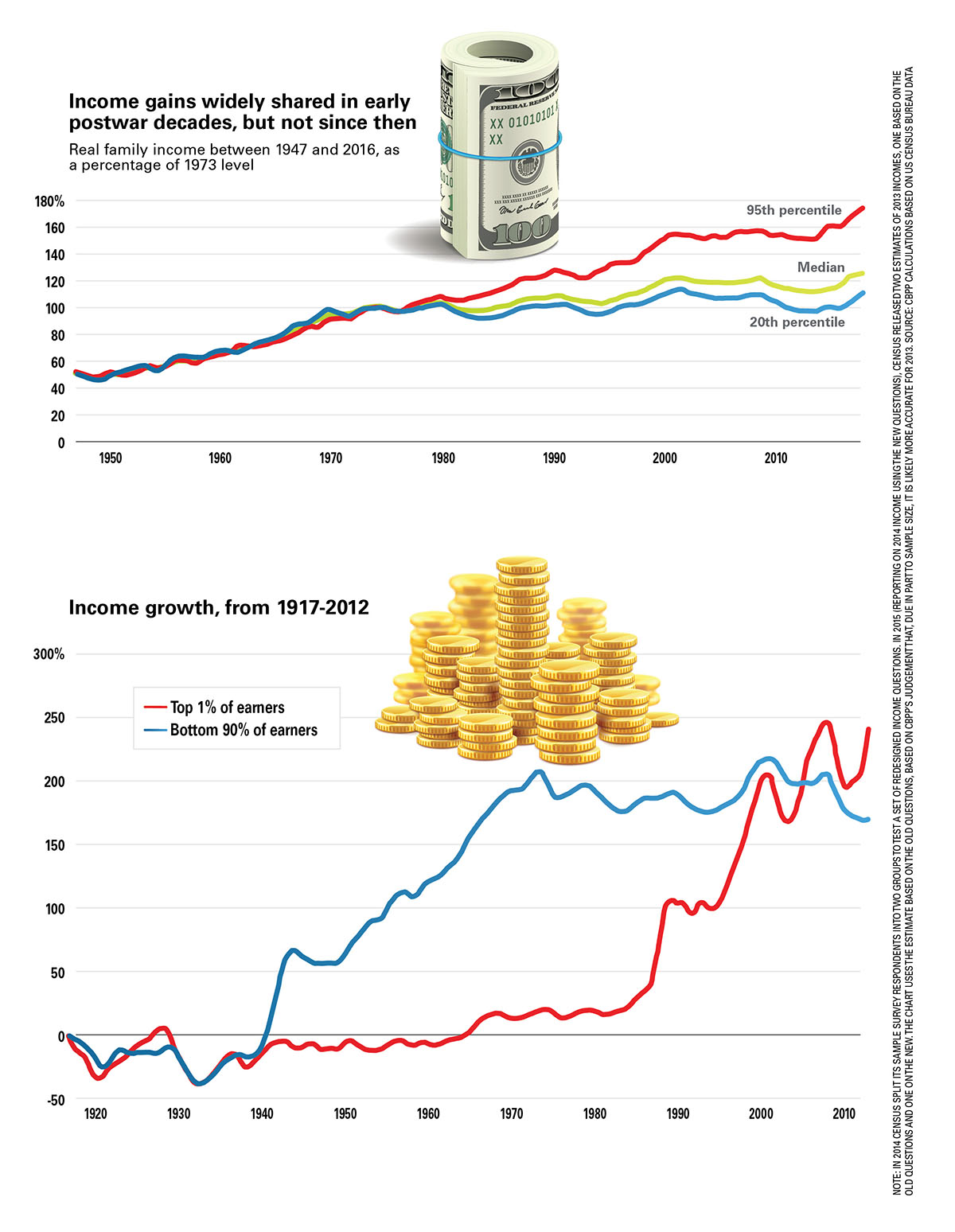

Income inequality, for example, began to get much worse.

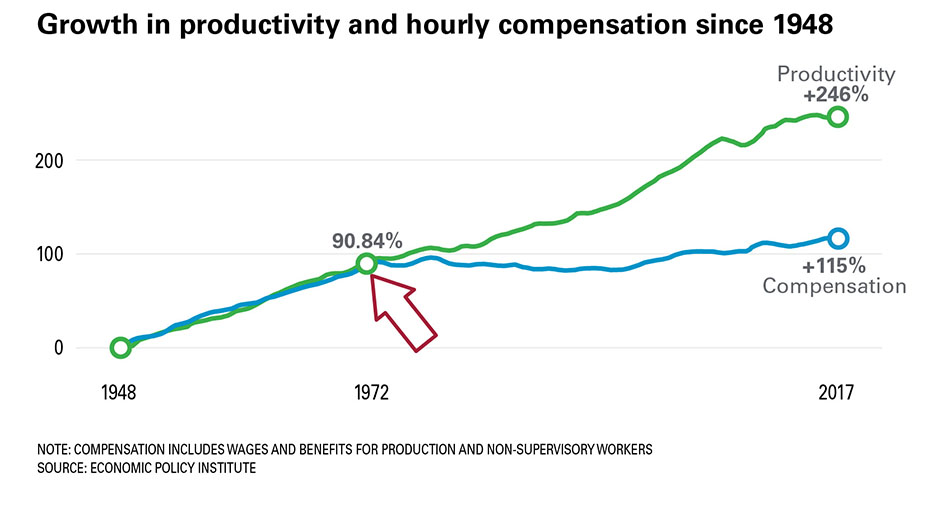

Wages, which had tracked closely with productivity and GDP growth for decades, began to lag productivity and economic growth (badly).

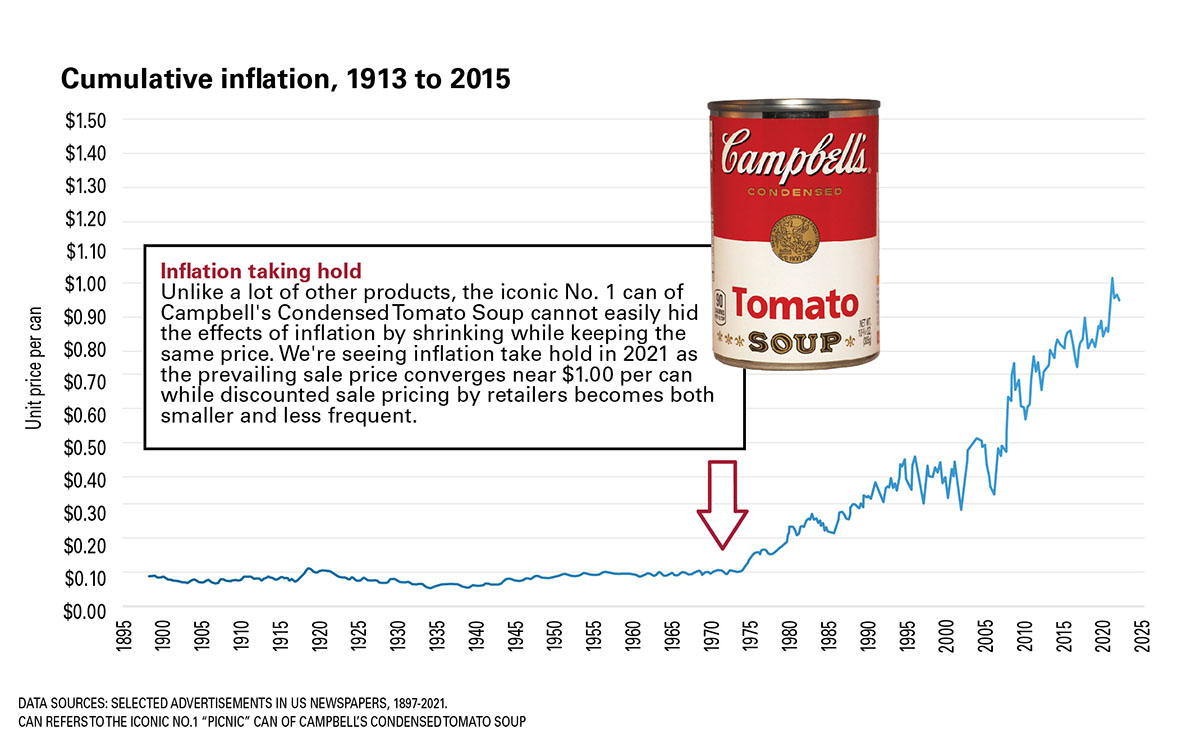

Inflation soared, growing at a faster rate than at any period in the previous century.

The income gap between black and white Americans, which had been closing rapidly since 1950, all but stopped closing.

These are just a few of the economic graphs one will find on wtfhappenedin1971.com. So the question remains: what the heck happened?

FDR, Nixon, and the Gold Standard

For years, I was bored to death when I’d hear discussions about the gold standard. Monetary policy wasn’t just dull, but confusing. Some people blamed Nixon for taking the US off the gold standard; others would say, “No, no. It was FDR.”

So, who was it? And what is “the gold standard,” anyway?

The gold standard is simply a monetary system that links the value of paper money to gold. The system, which was implemented in the U.S. in 1834, set the price of gold at $20.67 per ounce, where it stayed until the early 1933s. In the 1870s, other countries followed suit, ushering in the Golden Age of gold (pardon the pun) and a period of great prosperity.

“The period from 1880 to 1914 is known as the classical gold standard. During that time, the majority of countries adhered (in varying degrees) to gold,” writes Michael D. Bordo at EconLib. “It was also a period of unprecedented economic growth with relatively free trade in goods, labor, and capital.”

The period’s end—1914—came with the beginning of World War I, when many nations turned to inflationary finance to pay for the bloodiest war in human history (at the time). From 1925 to 1931 a new gold era began with the Gold Exchange Standard, but it didn’t last long.

“This version broke down in 1931 following Britain’s departure from gold in the face of massive gold and capital outflows,” Bordo explains. “In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt nationalized gold owned by private citizens and abrogated contracts in which payment was specified in gold.”

FDR’s order—Executive Order 6102—forbade “the hoarding of gold coin, gold bullion, and gold certificates within the continental United States.”

Not only would individuals not be able to redeem their paper notes for gold under the order, but private ownership of gold coins and bullion was made illegal. (This unpopular law was repealed in 1974.)

So, what about Nixon?

So, it was FDR that moved the U.S. off the gold standard? Not quite.

From 1946 to 1971, nations operated under a new monetary system: the Bretton Woods Agreement.

“The Bretton Woods system was designed by the Allied nations, led by the United States, near the end of World War II as a postwar international monetary order,” explains economist Jonathan Newman. “The U.S. dollar would become the world’s reserve currency, which foreign governments could redeem for gold, even though U.S. citizens could not.”

Did you catch that last part? Though citizens couldn’t exchange paper money for gold, foreign governments could. So, the U.S. dollar was still tethered to gold, which the U.S. promised to redeem at an exchange rate of $35 per ounce. This meant the U.S. couldn’t inflate the money supply without depleting its gold reserves.

Unfortunately, however, the U.S. did inflate its currency, in large part to finance the escalating costs of the Vietnam War and LBJ’s Great Society.

This is one reason, Newman explains, that the U.S. depleted roughly 55 percent of its gold stock from the 1950s to 1971.

In that year—1971—facing depleted gold reserves and a dollar facing increasing inflationary pressure from government expenses, Nixon made a critical decision: he “temporarily” paused gold redemption.

Nixon’s move was not temporary, however.

That’s what happened in 1971

Now you know what happened in 1971. The U.S. became what is known as a fiat currency system, one in which paper is legal tender backed not by gold, silver or some other commodity, but by government decree.

Economist Thorsten Polleit described three things all fiat monies have in common: (1) Government (or its central bank) has the monopoly on production; (2) It is created by way of bank credit expansion (i.e. out of thin air); (3) It has no inherent value, it is simply brightly colored paper (or digital bytes) that can be produced whenever those in power deem it politically expedient.

A fiat money system allows them to finance all the programs and agendas they otherwise couldn’t afford.

Unfortunately, all that spending comes at a cost. The federal debt ballooned from $398 billion in 1971 ($2.7 trillion 2021 dollars) to $28.8 trillion today. But as the charts show, those are hardly the only costs.

Economist Murray Rothbard liked to use a thought experiment to demonstrate how it worked. Imagine if “Angel Gabriel” appeared and multiplied the amount of money everyone had tenfold. Would anyone be richer?

Not one bit. But now imagine that the money supply is increased, but not distributed evenly. The Angel Gabriel increases the money supply for some—starting with privileged bankers who decide how it is distributed—but not others.

Who benefits then? You guessed it: those who get it first.

Edward Snowden and Jack Dorsey are asking the right question: what the [heck] happened in 1971? We know what happened, the question is: what will we do about it?

Monetary policy may be confusing and some may find it dull—though I no longer do. But one thing is clear: it’s monumentally important.

Excerpt Jonathan Miltimore, fee.org