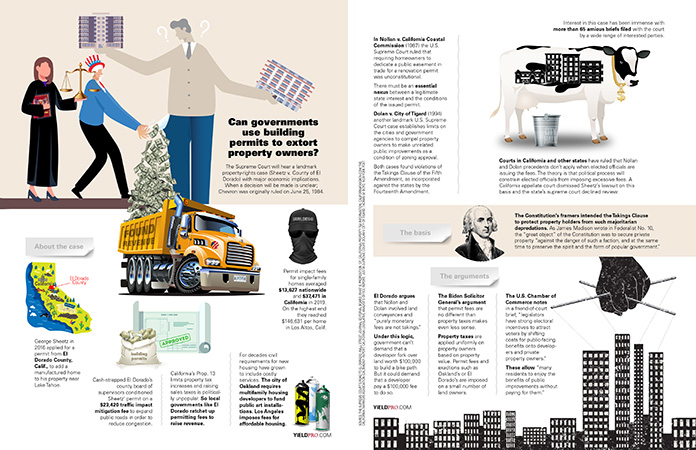

The Supreme Court will hear a landmark property-rights case (Sheetz v. County of El Dorado) with major economic implications. When a decision will be made is unclear; Chevron was originally ruled on June 25, 1984.

The Supreme Court will hear a landmark property-rights case (Sheetz v. County of El Dorado) with major economic implications. When a decision will be made is unclear; Chevron was originally ruled on June 25, 1984.

About the case

George Sheetz in 2016 applied for a permit from El Dorado County, Calif., to add a manufactured home to his property near Lake Tahoe.

Cash-strapped El Dorado’s County board of supervisors conditioned Sheetz’ permit on a $23,420 traffic impact mitigation fee to expand public roads in order to reduce congestion.

California’s Prop. 13 limits property tax increases and raising sales taxes is politically unpopular. So local governments like El Dorado ratchet up permitting fees to raise revenue.

For decades civil requirements for new housing have grown to include costly services. The city of Oakland requires multifamily housing developers to fund public art installations. Los Angeles imposes fees for affordable housing.

Permit impact fees for single-family homes averaged $13,627 nationwide and $37,471 in California in 2019. On the highest end they reached $146,631 per home in Los Altos, Calif.

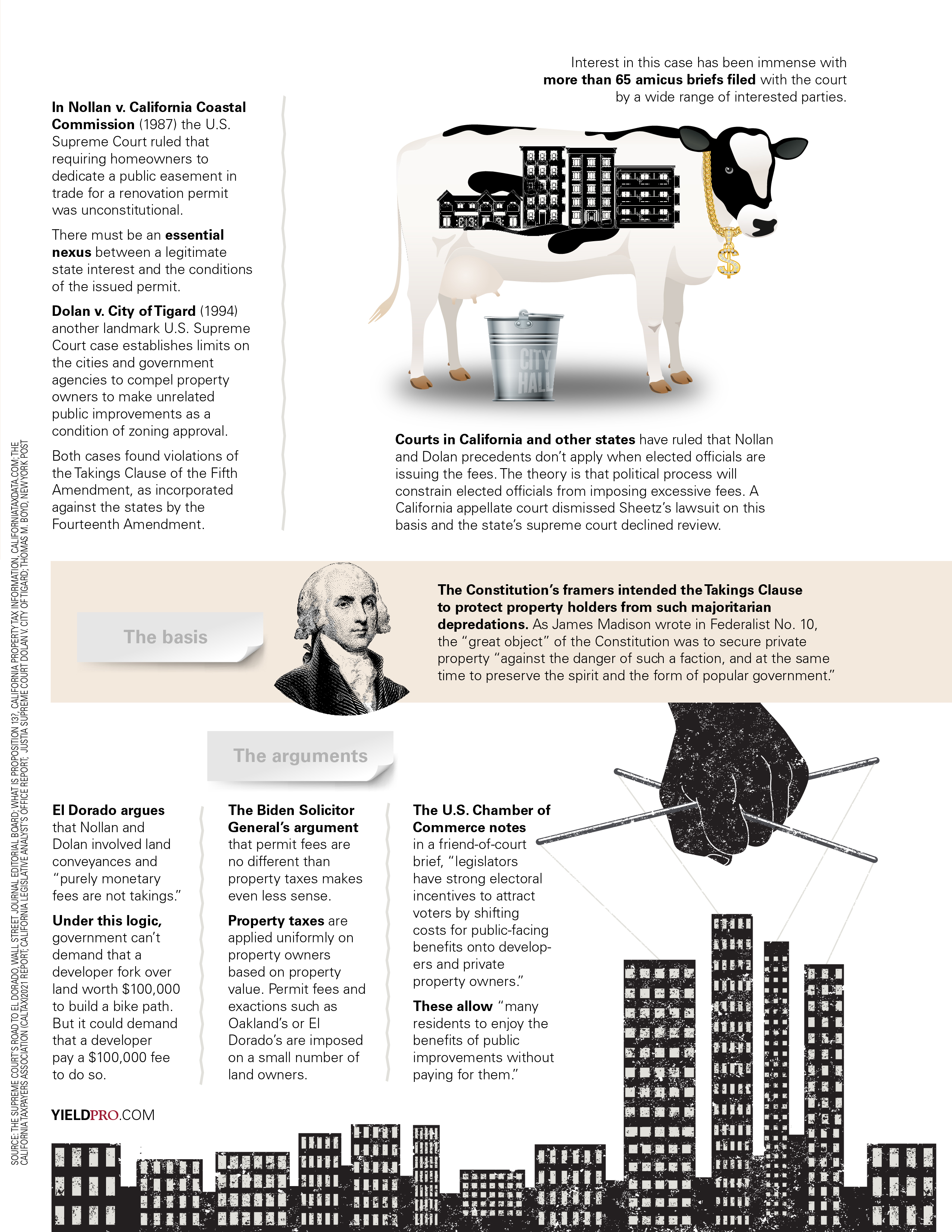

In Nollan v. California Coastal Commission (1987) the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that requiring homeowners to dedicate a public easement in trade for a renovation permit was unconstitutional.

There must be an essential nexus between a legitimate state interest and the conditions of the issued permit.

Dolan v. City of Tigard (1994) another landmark U.S. Supreme Court case establishes limits on the cities and government agencies to compel property owners to make unrelated public improvements as a condition of zoning approval.

Both cases found violations of the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment, as incorporated against the states by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Interest in this case has been immense with more than 65 amicus briefs filed with the court by a wide range of interested parties.

Courts in California and other states have ruled that Nollan and Dolan precedents don’t apply when elected officials are issuing the fees. The theory is that political process will constrain elected officials from imposing excessive fees. A California appellate court dismissed Sheetz’s lawsuit on this basis and the state’s supreme court declined review.

The basis

The Constitution’s framers intended the Takings Clause to protect property holders from such majoritarian depredations. As James Madison wrote in Federalist No. 10, the “great object” of the Constitution was to secure private property “against the danger of such a faction, and at the same time to preserve the spirit and the form of popular government.”

The arguments

El Dorado argues that Nollan and Dolan involved land conveyances and “purely monetary fees are not takings.”

Under this logic, government can’t demand that a developer fork over land worth $100,000 to build a bike path. But it could demand that a developer pay a $100,000 fee to do so.

The Biden Solicitor General’s argument that permit fees are no different than property taxes makes even less sense.

Property taxes are applied uniformly on property owners based on property value. Permit fees and exactions such as Oakland’s or El Dorado’s are imposed on a small number of land owners.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce notes in a friend-of-court brief, “legislators have strong electoral incentives to attract voters by shifting costs for public-facing benefits onto developers and private property owners.”

These allow “many residents to enjoy the benefits of public improvements without paying for them.”

SOURCE: THE SUPREME COURT’S ROAD TO EL DORADO, WALL STREET JOURNAL EDITORIAL BOARD; WHAT IS PROPOSITION 13?, CALIFORNIA PROPERTY TAX INFORMATION, CALIFORNIATAXDATA.COM; THE CALIFORNIA TAXPAYERS ASSOCIATION (CALTAX) 2021 REPORT; CALIFORNIA LEGISLATIVE ANALYST’S OFFICE REPORT; JUSTIA SUPREME COURT DOLAN V. CITY OF TIGARD; THOMAS M. BOYD, NEW YORK POST