I was stymied by a bubbling major depression, which would have been my third since November, so I consulted with my psychiatrist about switching medications.

The thing about psychoactive medication is that isn’t like switching from aspirin to ibuprofen. Patients need to taper off one drug and slowly add in the new one or risk serotonin syndrome—a nasty malady that involves fevers, anxiety, confusion and a host of other physical symptoms.

I didn’t endure serotonin syndrome; I continue to struggle with increased depression, anxiety and insomnia during the transition. The symptoms were acute enough that I needed some time away from work.

One thing I learned from this bout of depression is that as a society, we lack a good vocabulary for talking about mental health.

This is an especially difficult challenge for friends and loved ones who have not suffered from a mental health issue but care about someone who does.

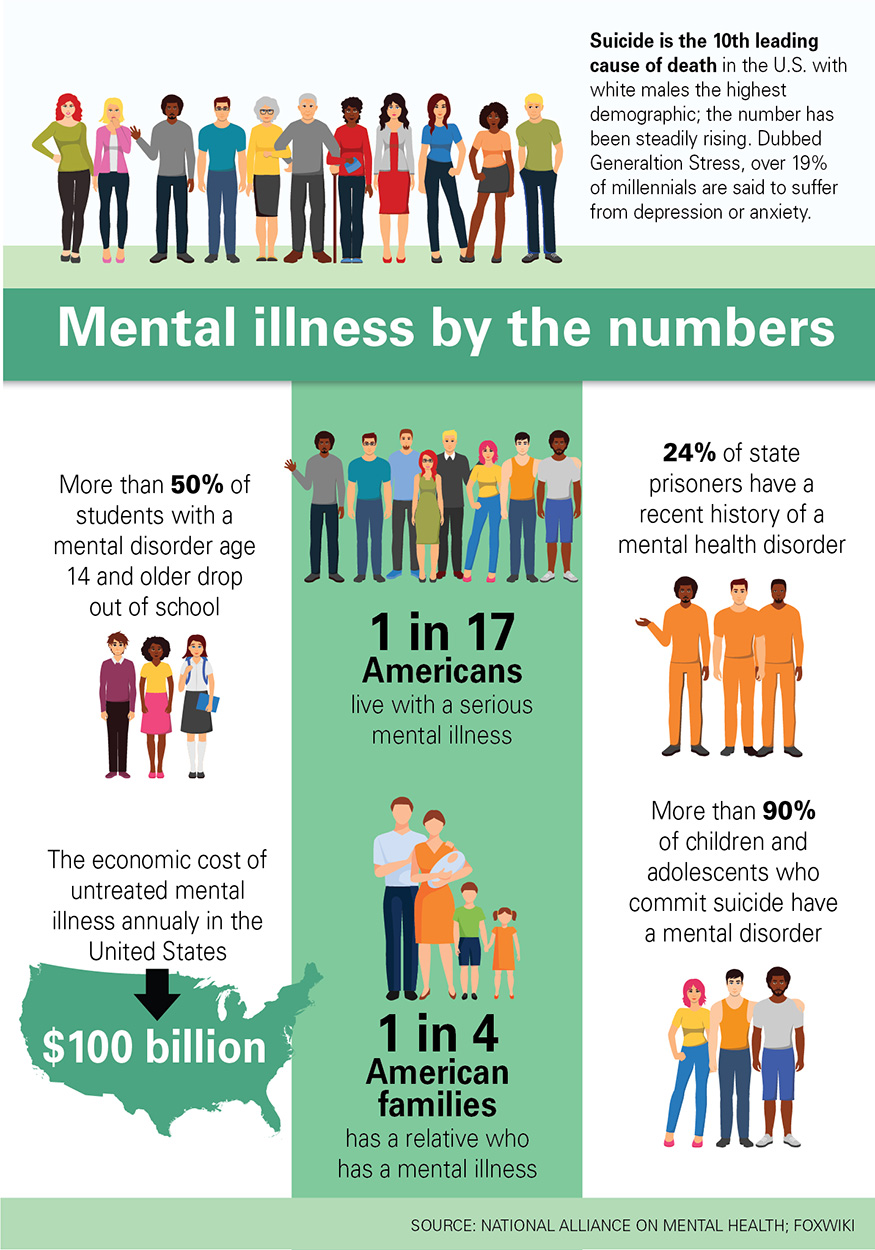

Nearly a fifth of all Americans suffer from mental illness. That amounts to about 620,000 Iowans, according to a report by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

The most common mental health issue is anxiety disorders. The Anxiety and Depression Association of America estimates 18 percent of Americans, or about 558,000 Iowans, live with anxiety disorders; I’m one of them.

Depression affects about 7 percent of the U.S. population, about 217,000 Iowans; I’m one of them, too.

Yet despite the obvious prevalence of mental health issues, talking about it often is a struggle.

“It’s impossible for people who have not experienced major depression to understand the depths of those feelings,” said Peggy Huppert, executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Iowa. “This isn’t sadness we’re talking about. It’s like falling into a pit and feeling like you’re never going to hit the bottom.”

So outside of experiencing it personally, which I would not wish on anyone, I talked to some local mental health experts for some tips on talking with loved ones who struggle with mental health issues.

Here’s what they said:

Listen

When we see a loved one hurting, we want to help. We want to fix the problem. Dealing with mental illness is more complex. It requires more patience, open-mindedness and empathy than most daily troubles.

“Ask a person who is struggling, ‘Tell me your story,’” said Kent Schornack, director of Grand View University counseling services. “Everyone’s story is unique. Invite a conversation. Say, ‘Help me understand what you’re going through.’ Demonstrate your caring by listening. That’s often the most important thing any of us can do.”

Educate yourself

One of the most common responses I receive from well-meaning friends and family when I say I’m struggling with depression or anxiety are pithy declarations such as, “change your thoughts.” Believe me, if it was that easy, we would flip the light switch to “happy thoughts” and duct tape it to the “on” position.

Alas, brain chemistry and thinking patterns are much more complicated.

“Depression is a chemical imbalance in the brain that has negative effects on moods and physical health,” said Vanja Duric, a professor of psychology and pharmacology at Des Moines University. “Even when taking medication to control depression, it takes a long time—sometimes two to four weeks—for the effects of those drugs to be seen. It isn’t like an infection in which you get an antibiotic and in a day or two, you start to feel much better.”

Depression also exists on a spectrum. Most people will experience situational depression in their lifetime—think the intense sadness felt after the death of a parent or loved one. This kind of depression can be treated over a relatively short period.

However, major depression or bipolar disorder, for example, are chronic, lifelong problems that require regular monitoring and have high instances of recurrence.

Good resources for learning about mental health include the National Alliance on Mental Health, Anxiety and Depression Association of America and the Mayo Clinic.

Ask, but don’t tell

The author Ramsey Hootman is an acquaintance of mine through Twitter and Instagram. We’ve never met in person, but we have had delightful exchanges through social media—something rare in the world of social media.

Hootman mentioned my writing about the connection between mental wellness and obesity in the acknowledgments of her book Surviving Cyril.

Recently, when I made several posts about being depressed, she sent me a message and asked if I was getting help. (I am and have been for years.) The question, though, was perfectly posed.

Hootman wasn’t telling me what to do. She was checking on my welfare. That’s an important distinction.

“We have to respect that people are at different points on their journey,” Huppert of NAMI Iowa said. “Sometimes a blunt declarative: ‘Go see a therapist’ can do more harm than good. Make sure your conversations with your loved ones emphasize your love and empathy for them.”

Be present

Mental illness isn’t a communicable disease. You won’t catch it because you shook hands or hugged someone with mental illness.

I have seen people keep their distance from me when I’m struggling. I believe they simply don’t know what to say or how to offer comfort.

Sometimes I’m not looking to talk about my mental health at all. One of the most successful ways I’ve found to find relief is a lengthy phone conversation with my friend Paul, a former Drake University classmate who lives in Memphis.

Paul and I talk about movies, sports and politics. The only time mental health comes into the talks is when I thank my dear friend for the dialogue which invariably lifts my mood.

The point is sometimes what we need is a distraction rather than a dissection of our disease. This comes with an important caveat.

Friends and loved ones “should do some self-assessment,” said Schornack. “If you’re not able to be there for someone, know your limits and don’t offer to help or be there when you can’t. You don’t want to be like Lucy, jerking the football away from Charlie Brown.”

Embrace empathy

One of my most persistent fears is that I am somehow lesser than others who are not fellow travelers with mental health issues.

Most people I meet or speak with directly are supportive. And I’m happy to report that no one, not even the worst of internet trolls, has suggested I’m unfit for this job because of my openness about mental illness—at least not that I’ve seen.

I often cite Fred Rogers, the late children’s educational television pioneer. I regularly say my life goal is to be a little bit less Incredible Hulk and a lot more Mr. Rogers.

A Rogers quote that I hold dear is: “To love someone is to strive to accept that person exactly the way he or she is, right here and now.”

I am blessed to have many people in my life who live that maxim. I hope to be that kind of person for the people in my life, though I often fall short.

As Mark Kloberdanz, director of the Drake University Counseling Center, said: “Sometimes the best thing you can do is tell someone you love them and accept them.”

Author: Daniel P. Finney, Des Moines Register