Housing inflation continues to be a stubborn impediment to the consumer price index (CPI) falling back to the Federal Reserve’s target.

Despite broader economic inflation cooling significantly from pandemic peaks, the shelter inflation index has remained elevated, largely due to how the BLS calculates housing costs.

Understanding the numbers

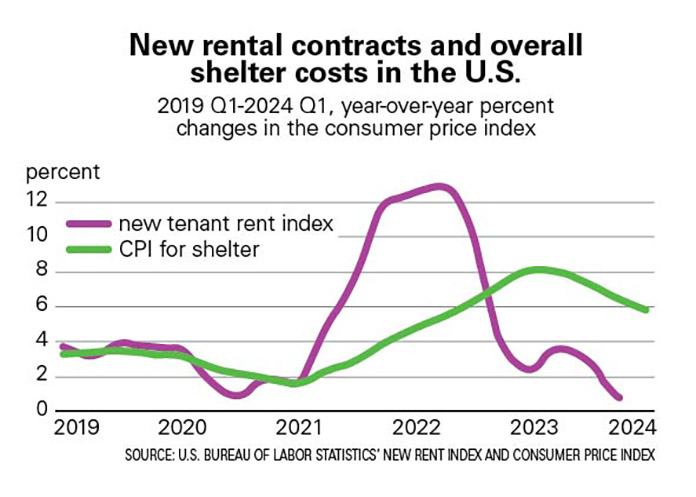

Economists note that the CPI shelter index lags behind real-time rent trends. While the annual inflation rate for new rental contracts fell to 0.4 percent in 1Q24, the shelter index only fell to a 5.2 percent annual rate in June from a peak of 8 percent in early 2023.

The BLS methodology involves a “staggered panel” approach, where renters and homeowners are surveyed every six months in rotating groups. This results in a slow-moving index that reflects past conditions rather than current market dynamics.

Consequently, CPI data lags by about 9 to 12 months, delaying the reflection of real-time drops in rents.

Outsized influence

Notably, housing costs make up 36 percent of the CPI, which means shelter inflation is a significant factor in overall inflation readings.

The “owners’ equivalent rent” (OER) category is used to estimate the rental value of owned homes, further complicating the calculation as it doesn’t directly measure home purchase costs.

Broader implications

As the shelter inflation index lags, it affects the Federal Reserve’s policy decisions. The slow moderation of shelter inflation impacts overall CPI, complicating the Fed’s efforts to control inflation.

Additionally, rents surged during the pandemic due to demand outpacing supply, but with more multifamily units being built, rental growth is slowing, which should eventually be reflected in the CPI.