Of course, there are some obligatory qualifiers for that optimism. Most economists continue to project sustained moderate growth; but if a national recession takes root, that changes everything. And gone are the days of a rising tide boosting all segments of the apartment market. Segmentation is the keyword going forward.

But before we go there, let’s first discuss the increasingly loud chorus of skepticism about apartments—particularly from lenders and regulators. A Wall Street Journal headline earlier this year ominously screamed: “Apartment Market Slumps as Supply Surges.” And the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, a key regulator, recently warned of “froth” in the apartment market. Banks have responded by tightening multifamily lending standards in each of the past eight quarters, according to the Federal Reserve’s survey of senior loan officers.

The sense that the rising tide just can’t go on is partly human nature—that all good things must come to an end. But it’s also due to persistent misconceptions of apartments and the people who live in them.

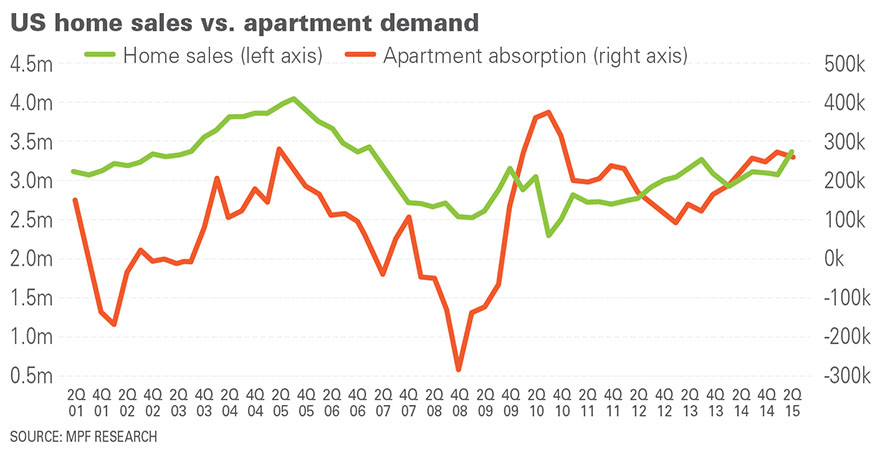

When the apartment boom first started in 2010, conventional wisdom linked rising apartment demand with the collapse of the for-sale housing market. But there’s plenty of evidence this was always a myth. (Most of those people chose to rent single-family homes, often because their credit disqualified them in the multifamily screening process.) There’s no evidence that foreclosed homeowners ended up renting apartments. Furthermore, demand for apartments generally grows when home sales grow.

Historical trends teach us there are two simple, foundational drivers of apartment demand—demographics and the economy. Every other factor ranks miles behind the big two. We discussed the economy earlier. If you doubt the consensus forecast of sustained moderate economic growth, then you have good reason for skepticism toward the apartment market—and nearly any other investment.

That takes us to demographics. Millennials are rightly given a lot of credit for fueling apartment demand. But today’s multifamily skeptics now fear the very people who drove the boom will now drive an exodus as they age, get married, have kids and move into single-family homes.

To be clear, we do expect more Millennials to leave for apartments as their life stages evolve. This begs another question: with the Millennials getting older, won’t we see the drop-off we’ve been waiting for? Not really—at least not to the magnitude you might expect. Moody’s is forecasting that the U.S. will add more people than it loses in the key 25- to 34-year-old age cohort for at least the next six years. That means that as a 35-year-old leaves to buy a house, a 25-year-old is moving into their old apartment.

To be fair, though, the pace of growth in the young adult population is slowing. Back in 2011, the U.S. netted growth of more than 1 million people in its 25- to 34-year-old population. That was the biggest increase since the last of the Baby Boomers surged into that group in 1981. We’ll add about one quarter of that figure in 2017 and again in 2018, according to Moody’s. The net population change figures fall slightly negative in Moody’s forecasts by 2023.

But demographic drivers go deeper than young adult population trends. In 2017, economists from the St. Louis Fed noted apartment demand should benefit from more young adults leaving their parents’ homes, and from downsizing baby boomers.

All in all, there’s little reason to expect a big slowdown in apartment demand independent of a broader economic slowdown.

What does this mean for the outlook? Multifamily will continue to grow, just not quite as rapidly. And furthermore, there will be clearer lines between winners and losers in the apartment space. Segmentation at this point in the cycle is critical, and this could mean trouble for investors and lenders who have not adjusted strategies by now.

Strong and not-so-strong

Big lenders and investors historically tend to favor luxury, expensive buildings in the downtowns of major cities. That investment strategy is built on the assumption of greater liquidity should the need to sell arise.

The urban preference indeed shows up in the capital markets data. According to a price index from Real Capital Analytics, pricing on such deals has more than doubled from the pre-recession peaks seen in 2007. Cap rates can come in below 4 percent, far below the national apartment average around 5.5 percent.

But underlying fundamentals—rents and demand—haven’t seen nearly the same bias toward big-city downtown apartments. RealPage lease-transaction records show the average rent roll premium for an urban apartment property compared to a top-end suburban counterpart has eroded by 9 percentage points on a same-store basis over the last five years. Suburbs have consistently outperformed on rent growth since the second half of 2013, and that trend won’t disappear anytime soon.

Simply put, the flood of capital chasing urban, luxury apartments has created a surge in new supply that—in turn—creates challenges for investors to achieve pro forma growth. Anyone who bought the conventional wisdom that urban areas offered higher barriers to entry were buying into a badly outdated principle. Urban construction has outpaced that of the suburbs for the last decade—and by a longshot. That, too, won’t change anytime soon.

Abundant supply makes it easy for renters, often light on possessions, to move two blocks away to a tempting property offering special incentives—particularly if the bloom is off the rose where they currently live. These renters are relatively affluent, upwardly mobile, and in fact mobile in general.

So where are the deals to be had? As we’ve been saying lately, it’s in the suburbs, where barriers to entry have limited development unlike in urban cores where cities have incentivized it. Despite the perception that developing in the suburbs means buying land on the outskirts of what’s already there, the opportunities are in in-filling already developed areas that have retail, schools, transportation and other amenities. Of course, there’s “NIMBY” at work, with suburban homeowners not wanting high-density development and policy-makers fearing overloaded infrastructure. But those who can overcome the barriers to entry will find higher returns than they would elsewhere.

Class B working class developments, while not as glamorous as glossy downtown projects, also still offer plenty of potential.

In summary, barring some unexpected event that tanks the economy in general, we don’t anticipate a substantial fall-off in the current positive cycle. And if there is some sort of broad economic disaster, the multifamily sector won’t necessarily end up as badly off as others, so it would likely be a matter of “bad for us, worse for the rest.” Since money has to go somewhere, and people have to live somewhere too, multifamily continues to look quite good.

Author: Jay Parsons