You might have seen the headlines:

“Supreme Court Just Defeated Big Government” (Fox News), “Guts Agency Power” (Axios), “Imperils an Array of Federal Rules” (New York Times).

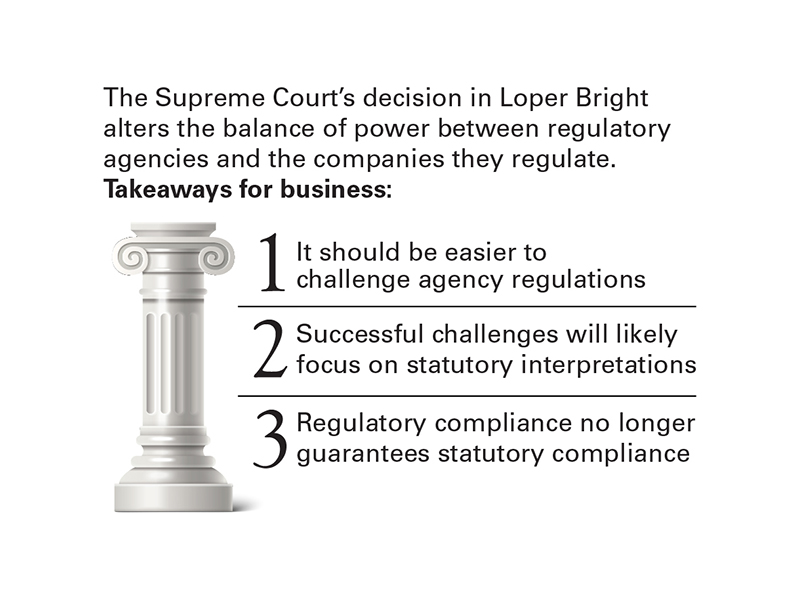

In August 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a long-standing precedent called the Chevron Doctrine in its 6-3 decision in the case of Loper Bright Enterprises et. al. v. Raimondo, Secretary of Commerce, et. al.

Lawyers are likely to be busy for years because of this decision, which gives courts new power to second-guess rules and regulations made by federal agencies.

For apartment owners, managers and developers, the Supreme Court decision is likely to affect a long list of federal rules on issues that matter to them—from tenant screening to how local governments handle their zoning.

“You are going to see many, many regulatory lawsuits premised on the Loper decision,” said Paula M. Cino, vice president for construction, development, land use and counsel for the National Multifamily Housing Council, based in Washington, D.C. “It is having an immediate impact in litigation right now.”

What’s Chevron Doctrine?

For four decades, a legal precedent called the Chevron Doctrine, and other precedents like Chevron, required federal courts to give deference to federal agencies that made reasonable interpretations of ambiguous language in laws passed by Congress. The doctrine was based on the Supreme Court’s decision in 1984 in Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council.

In their decision this summer, the Supreme Court overturned the 1984 decision.

“This shift in power favors companies and organizations, as courts are no longer required to defer,” said Ayiesha Beverly, general counsel for the National Apartment Association, based in Arlington, Va.

The basic facts of the recent Supreme Court decision may provide more clues about how courts may view the actions of federal agencies in future cases.

Loper Bright Enterprises is a family-owned fishing company based in New Jersey operating off the coast of New England. Fishing companies in the area had long been subject to a 1976 federal law that said the agencies may require vessels to carry federal monitors on board to prevent overfishing. The law did not say who would pay for the monitors. Loper Bright sued after federal agencies began charging the fishing industry in 2020.

The Supreme Court decision didn’t overturn the law. The majority decision also reiterates that federal agencies have some latitude in how they fulfill the mandates set by Congress. But the court disagreed with the agency on questions about whether the law allows the government force private fishing boats to pay for these monitors, according to the decision.

“Courts may not defer to an agency interpretation of the law simply because a statute is ambiguous,” according to the majority 6-3 decision. “The Administrative Procedure Act requires courts to exercise their independent judgment.”

Still waiting for Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing

The Supreme Court’s decision probably began to affect some aspects of the apartment business as soon as it was published.

Federal agencies likely immediately began to consider how the unexpected end of the Chevron Doctrine would affect their regulations.

“The agencies are probably taking a closer look at the rules that they are writing,” said Tom Ward, vice president of legal advocacy for the National Association of Home Builders.

For example, officials at the U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) have not yet issued their final rule on Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing, which many expected to be released earlier in 2024.

“They know they are likely to get sued over it,” said Ward.

The rule has a tortured history. HUD created its first Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule under the Obama Administration. It was repealed under the Administration of President Donald Trump. Under the Administration of President Joe Biden, HUD released a new interim final rule and a proposed rule, received public comments and has been poised to release a final rule.

The end of Chevron deference has probably delayed the release of the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule—maybe permanently. New federal rules are rarely released close to federal elections or in the lame duck period afterward.

If Donald Trump again becomes president, he is unlikely to release the rule, said Ward.

If the rule is eventually released, it would require cities and towns across the U.S. that receive money from HUD to submit extensive reports every three to five years on how they plan to “affirmatively further” Fair Housing.

Specifically, they would have to analyze their housing occupancy by race, disability, familial status, economic status, English proficiency and other categories. They would then have to identify factors which contribute to prohibitive barriers in housing and create a plan to fix the problems.

If the Federal government was not satisfied with a community’s efforts to reduce demographic disparities, federal funds could be withheld.

The rule could effectively force communities that have resisted new development to allow the construction of new rental housing, including affordable housing—or risk losing HUD funding like Community Development Block Grants. “These jurisdictions would have standing to sue, because they have to do something about this,” said Ward.

The proposed revival of the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule is based on law passed by Congress. The Fair Housing Act states that: “All executive departments and agencies shall administer their programs and activities relating to housing and urban development (including any Federal agency having regulatory or supervisory authority over financial institutions) in a manner affirmatively to further the purposes of” the Fair Housing Act.

“The overreach is in the details,” said Ward. “‘Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing’ is unclear. Exactly how do I further the purposes of the Act?”

However, HUD is not free to ignore a law passed by Congress because it is ambiguous. If HUD did nothing to affirmatively further fair housing, the agency could be sued by fair housing advocates.

“That may be the basis of an Administrative Procedure Act claim,” said Morgan Williams, general counsel for the National Fair Housing Alliance, based in Washington, D.C. Either way—whether a federal agency is sued for doing too much or too little—the court would be tasked with resolving the ambiguities in the stature. “The question then becomes is the agency implementing the right reading under the law.”

Apartment developers still wait for wetland permits

The Supreme Court’s recent decision is also already making a difference in the legal fight over how developers handle wetlands on sites where they want to build new apartments.

“In Texas, we are challenging the agencies’ definitions,” said Tom Ward, vice president of legal advocacy for the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB).

Lawyers representing housing developers filed a lawsuit against the Environment Protection Agency and the Army Corp. of Engineers in January 2023. The plaintiffs claim the agencies have gone too far in their enforcement of the federal Clean Water Act, created by Congress in 1972 to protect the waters of the US from a variety of harms.

Currently developers need to get a permit from the Army Corp of Engineers whenever their work adds fill material to a wetland the agencies consider to be one of the Waters of the United States. It takes months to get a consultant to visit a site and determine whether it includes a wetland that would require a permit. Then it takes an average of one year (313 days) to get a general permit and two years (788) to get an individual permit, according to a 2002 study.

Developers and federal agencies have been arguing for years in court over which wetlands should require these permits. “For a multifamily developer, it gets down to whether they are going to buy a property that includes a wetland,” said Ward.

“The end of Chevron Deference is likely to be a part of the next court decision on the Clean Water Act,” said Ward. “When we get an opinion from a court on this regulation, I think the court is going to say: ‘Remember, we don’t defer to the agency anymore.’”

In some ways, the Supreme Court decision in the Loper Bright is just the latest milestone in its long journey away from the Chevron Doctrine and toward questioning decisions made by federal agencies.

For example, in 2023, before Chevron was formally overturned this summer, the Supreme Court already questioned the agencies definition of the Waters of the United States. In the case of Sackett versus the Environmental Protection Agency (2023), the court overruled an earlier definition set by the agencies.

“In the Sackett decision they did not defer,” said Ward. In that decision, the court did not explicitly overturn the Chevron Doctrine. Instead, it simply did not mention the precedent. “It’s been eight years since SCOTUS referred to Chevron Deference,” said Ward.

Chief Justice John Roberts has also expressed his frustration with federal agencies that effectively make law for many years, according to Charles Lowery, senior director of policy for the National Housing Conference, based in Washington D.C.

In 2013, Roberts wrote a dissenting opinion in the case of Arlington v. FCC. Even then, he already argued that federal agencies were overreaching and doing things that should be decided by the courts, said Lowery.

“Agencies have no special competence in resolving statutory ambiguities,” Roberts writes in the Loper Bright decision. “Courts do.”

This shift of power from the agencies to the courts comes with no guarantee of how the courts will decide.

“If you have an administration that’s friendly to your industry, their regulations are going to be subject to review just like the regulations of an administration that is not friendly,” said NMHC’s Cino. “It’s just shift of power away from the federal agencies to the courts. We see it as giving industry and plaintiffs another tool, another opportunity for pushing back on regulatory overreach.”

HUD design standards may overreach

Lawsuits may also challenge design and construction standards effectively set by “safe harbors” issued by HUD.

“There’s a lot of money at stake when the government comes in and is seeking a widespread retrofit in a way that is not consistent with the Fair Housing Act,” said Lynn Calkins, partner with Holland & Knight, based in the law firm’s offices in Washington, D.C., and Nashville.

The agency has issued a variety of guidance over the years to designers and developers to help them build apartments that comply with Fair Housing law, which requires apartments to be accessible to people with disabilities.

These “safe harbor” guidelines specify that to comply with the law, all apartments in an elevatored building must be accessible to persons with disabilities.

HUD has filed many lawsuits claiming that properties are not accessible because they don’t follow one of these safe harbors. “Lots of courts have said those safe harbors are not required,” said Calkins. However, HUD’s enforcement stance still puts developers in the difficult position of having to demonstrate their buildings are accessible, even if they don’t follow the letter of the safe harbors.

“There is a possibility in light of the new rulings that developers could challenge those safe harbors as not being enforceable,” she said.

Lawyers question HUD guidance on prospective resident screenings

The methods used by many apartment companies to screen potential residents could also wind up being argued about in court.

“That seems like an area that’s ripe for a challenge,” said Holland & Knight’s Calkins.

The agency is especially concerned that when third-party screening companies use machine learning or artificial intelligence to accept or reject residents, they will disproportionately reject minorities, violating the Fair Housing Act.

“Tenant screening based on imprecise or overly broad criteria may unjustifiably exclude people from housing opportunities in discriminatory ways,” according to HUD’s “Guidance on Application of the Fair Housing Act to the Screening of Applicants for Rental Housing,” published in April 2024.

HUD’s guidance asks apartment managers and screening companies to perform an individual assessment based on relevant criteria and accurate records.

The process should be transparent to applicants, who should be able to challenge negative information, according to HUD. And screening companies should design and test complex models to see whether they comply with Fair Housing Law.

HUD already asks apartment companies to make an individual assessment of each candidate who fails a criminal background check, seeking a review of the particulars of the individual’s case. “But the number of people who have poor credit is much higher than the number of people who have criminal backgrounds,” said Calkins. Roughly a third of all credits scores are under 700, according to data from FICO.

“It’s practically impossible for the operators to comply with it on a portfolio-wide basis,” said Calkins. “It puts operators in a very complicated situation about how to even attempt to meet the desired standard.”

Requiring an individual assessment effectively requires leasing agents to make a subjective judgement on whether a potential resident with less than perfect credit should be accepted or rejected. That could also expose apartment companies to violating Fair Housing laws, said Calkins.

Apartment companies are also likely to have to spend significant time and money to comply with HUD’s guidance. “Most apartment operators would need hire an individual or teams of individuals to process applications,” said Calkins, who believe the guidance is beyond the scope of what the law passed by Congress intended.

“The question then becomes is somebody going to challenge it or are operators going to wait for HUD to attempt to enforce it and then in a defense posture explain that it’s beyond the scope of the new standard under Loper Bright.”

Federal agencies like the Federal Trade Commission and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau may also attempt to limit the fees the apartment companies can charge for screening residents.

“As agencies move forward and potentially finalize rules, that might be an area where you could see litigation,” said NMHC’s Cino. “That would certainly impact a wide swath of the industry.”