Key legal themes:

Takings clause

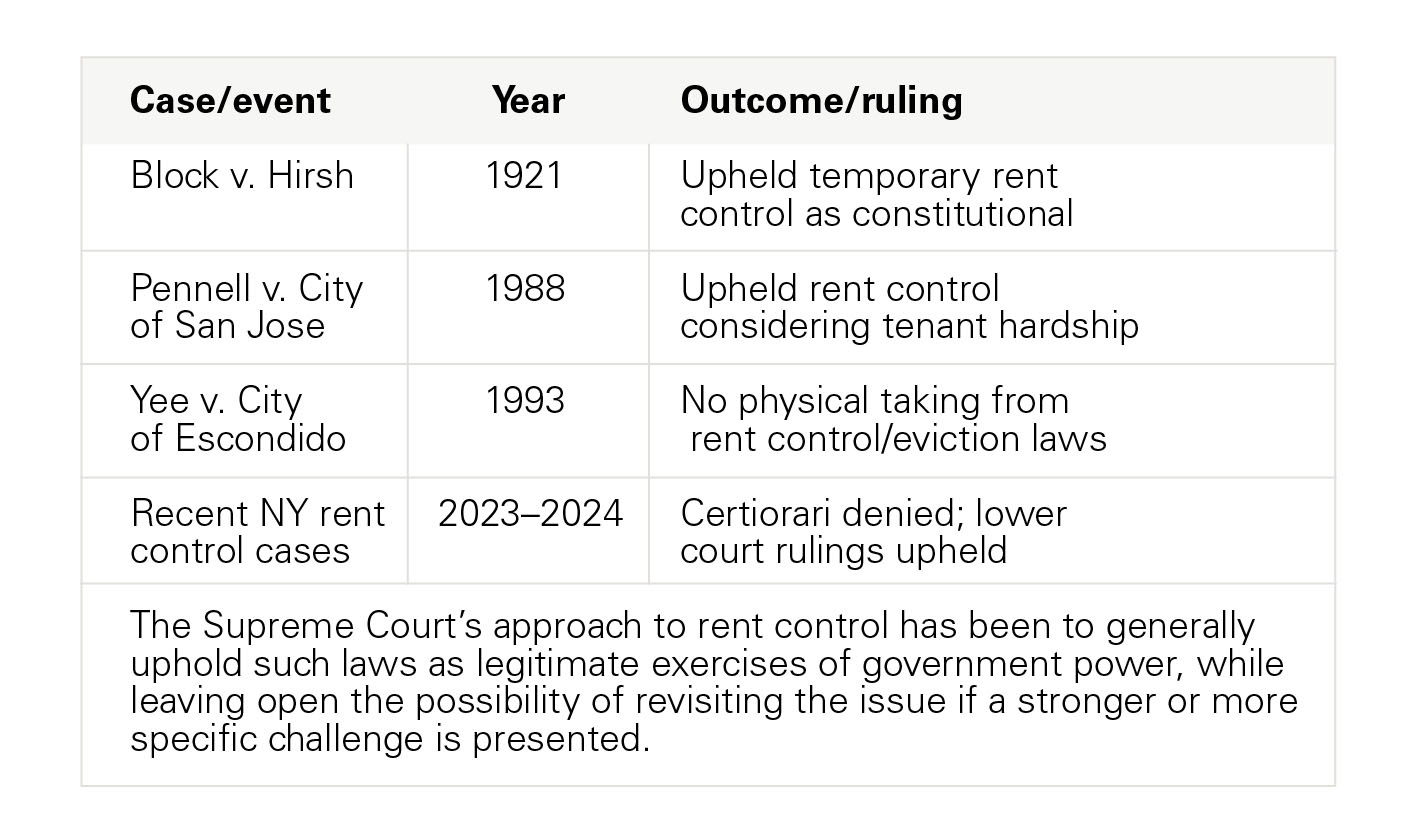

The Supreme Court has consistently held that rent control, as a regulatory measure, does not generally constitute a physical taking unless it compels a property owner to rent indefinitely or surrender possession permanently.

Police power

The Court recognizes that state and local governments have broad authority to regulate housing conditions and rents to promote public welfare, as long as such regulations do not amount to a taking without just compensation.

Ongoing debate

Despite repeated denials of certiorari, the Constitutionality of rent control remains a live legal issue, with some justices expressing openness to reconsidering the balance between property rights and tenant protections in an appropriate future case.

In the spring of 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the U.S., cities and states scrambled to enact emergency measures to protect public health and prevent mass homelessness. Los Angeles, like many other jurisdictions, imposed a sweeping eviction moratorium that prohibited landlords from removing tenants who could not pay rent due to the crisis.

What began as a public health measure, however, soon became the center of a legal battle with national implications—one that could reshape the rights of property owners and resident alike for years to come.

The story of GHP Management Corp. v. City of Los Angeles is, at its heart, a story about the tension between private property rights and government power during extraordinary times. GHP Management Corp., a major landlord in Los Angeles, found itself at the center of this storm.

By the time the company filed suit in August 2021, its residents owed over $20 million in back rent, and GHP had no effective means to evict them because of the city’s moratorium. The company argued that the city had, in effect, forced landlords to provide free housing to tenants, violating their rights under the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause.

Legal arguments

At the core of GHP’s argument was the idea that the city’s eviction moratorium constituted a “physical taking” of property. The Fifth Amendment requires the government to provide just compensation if it takes private property for public use.

GHP contended that by banning evictions for nonpayment, nuisance, or unauthorized occupants, the city had stripped landlords of their fundamental right to exclude others from their property—a right seen as central to property ownership in American law.

“The City in effect imposed and transferred to defaulting tenants an exclusive easement in the private property of others without paying for it,” wrote GHP’s attorneys in their petition to the Supreme Court.

To bolster their case, GHP pointed to the Supreme Court’s 2021 decision in Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid, which held that a California law allowing union organizers access to farm properties was a physical taking. GHP argued that, just as in Cedar Point, the city had authorized a physical occupation of private property—this time by tenants who were not paying rent.

The company also highlighted a growing split among federal courts on this issue. In 2022, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit ruled that Minnesota’s eviction moratorium was a per se physical taking under Cedar Point, and in August 2024, a panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit reached a similar conclusion regarding the federal government’s moratorium. However, the 9th Circuit, which covers California, disagreed.

In May 2024, it rejected GHP’s claim, holding that the moratorium merely adjusted the relationship between landlord and tenant and did not amount to a physical taking.

Lower court battles

GHP’s journey through the courts has been anything but smooth. The district court dismissed the case at the pleading stage, and the 9th Circuit affirmed that decision in a short, unpublished opinion.

The 9th Circuit relied heavily on the Supreme Court’s 1992 decision in Yee v. City of Escondido, which upheld a local rent control law, reasoning that “a statute that merely adjusts the existing relationship between landlord and tenant, including adjusting rental amount, terms of eviction, and even the identity of the tenant, does not effect a taking.”

The 9th Circuit distinguished Cedar Point, noting that the union organizers in that case were “interlopers with a government license,” whereas tenants under the moratorium were already in possession of the property with the landlord’s initial consent.

GHP and its supporters argue that the 9th Circuit has misread Yee and failed to appreciate the new rule from Cedar Point: that government-authorized occupations—even temporary ones—are takings when they deny owners the right to exclude. They contend that the moratorium was not a mere adjustment of the landlord-tenant relationship, but a government-mandated transfer of control from property owners to tenants, with no compensation for the landlords.

With the 9th Circuit’s decision against them, GHP turned to the Supreme Court, asking the justices to clarify the law and resolve the growing split among the federal circuits. The case was first scheduled for the Court’s conference in March 2025, but since then, it has been repeatedly “relisted”—meaning the justices have discussed it multiple times without deciding whether to take it up.

This could indicate that some justices are seriously considering granting review, or that one or more justices are writing a dissent from the Court’s decision not to take the case.

Legal observers note that the Supreme Court is often drawn to cases where federal appeals courts disagree on important legal questions, and GHP Management Corp. v. City of Los Angeles presents just such a split. If the Court takes the case, it will have the opportunity to clarify the scope of the Takings Clause in the context of eviction moratoriums and, potentially, other tenant protection laws.

The stakes in this case are high—not just for GHP and the City of Los Angeles, but for property owners and tenants across the country. If the Supreme Court sides with GHP and holds that eviction moratoriums are physical takings, it could open the door to billions of dollars in compensation claims against cities and states that enacted similar measures during the pandemic. It could also have far-reaching implications for other tenant protections, such as rent control and good-cause eviction laws.

Supporters of tenant rights warn that overturning or narrowing Yee v. City of Escondido could undermine decades of precedent and make it much harder for cities to enact laws that protect renters from sudden displacement.

Landlords and property rights advocates, on the other hand, argue that the government should not be able to commandeer private property for public use without paying just compensation, even during emergencies.

The broader context

The GHP Management Corp. case is part of a larger national debate about the balance between property rights and public welfare. The pandemic forced governments to make difficult choices, and the legal fallout from those choices is still unfolding.

The Supreme Court’s decision—if it takes the case—could set a precedent that shapes the future of housing policy in America.

Already, the Supreme Court has shown some sympathy for landlords’ arguments. In 2021, when the CDC extended its eviction moratorium for a fifth time, the Court paused the order, with the conservative justices noting that “preventing them from evicting tenants who breach their leases intrudes on one of the most fundamental elements of property ownership—the right to exclude.” This suggests that, if the case reaches the Supreme Court, the justices may be inclined to rule in favor of property owners.

The chances of Court review

As of June 2025, GHP Management Corp. v. City of Los Angeles remains in limbo on the Supreme Court’s docket. The repeated relists suggest that the justices are giving the case serious consideration, but it is far from certain that they will grant review.

Legal experts note that when a case is relisted multiple times, it often means that at least one justice is interested, but it does not guarantee that the Court will take the case.

If the Supreme Court does grant certiorari, the case could become a landmark decision on property rights and government power. If it denies review, the 9th Circuit’s decision will stand, and the split among the circuits will remain unresolved—at least for now.

GHP Management Corp. v. City of Los Angeles is more than just a dispute over unpaid rent. It is a test of the limits of government power during emergencies, a challenge to decades of housing law, and a potential turning point in the ongoing debate over property rights in America.

As the Supreme Court weighs whether to take the case, landlords, tenants, and legal scholars across the country are watching closely, knowing that the outcome could reshape the landscape of housing policy for years to come.