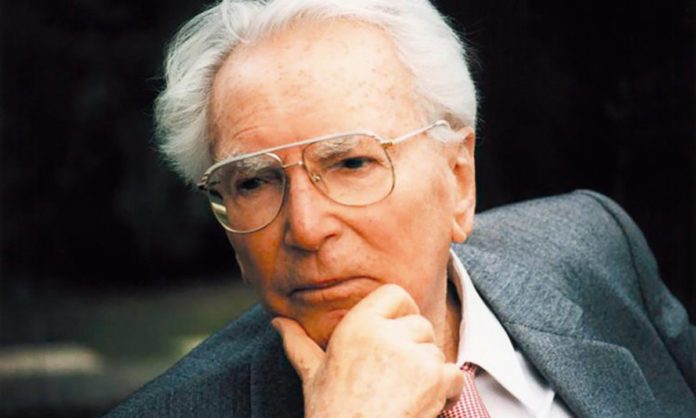

While imprisoned, Frankl realized he had one single freedom left: He had the power to determine his response to the horror unfolding around him.

And so he chose to imagine.

He imagined his wife and the prospect of seeing her again. He imagined himself teaching students after the war about the lessons he had learned.

Frankl survived and went on to chronicle his experiences and the wisdom he had drawn from them.

“A human being is a deciding being,” he wrote in his 1946 book, Man’s Search for Meaning, which sold more than 10 million copies. “Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

The idea of becoming conscious of the subjectivity of our perceptions is an admittedly abstract one—the stuff of philosophy and science fiction.

But human perceptions, and their ramifications, are very real and potentially life-changing.

For example, research shows that people may hold an unconscious bias against creativity because it represents uncertainty unless they are able to perceive that uncertainty in a positive light.

And consider the role perception plays in helping patients improve in ailments ranging from pain and depression to Parkinson’s disease through a phenomenon known as the placebo effect. Though the placebo effect remains largely shrouded in mystery, researchers attribute some aspects of the placebo response to active mechanisms in the brain that can influence bodily processes such as the immune response and release of hormones.

Studies also show that perceived risk can drive behavior change. The perception of the harmful effects of smoking, for example, can influence habit and addiction.

So how might we harness the power of perception to live more conscious lives and, perhaps, to even recast the most dire situations in which we find ourselves?

The fiction of reality

Perception begins when the human brain receives data from the body’s five senses. The mind then processes and applies meaning to the sensory information.

“I want to start with a game,” says neuroscientist and artist Beau Lotto at the outset of his TED talk on perception. “To win this game, all you have to do is see the reality that’s in front of you as it really is.”

As it turns out, seeing that reality isn’t as easy as it sounds, even when it comes to basic shapes and colors. Lotto uses a series of optical illusions involving light, color and space to show that even the most fundamental of our senses—the way we perceive light and color—can be subject to interpretation.

The variable, says Lotto, is context.

The exact same image can have an infinite number of sources in the real world. When it comes to perception—seeing, feeling, hearing, sensing things—there is no such thing as objectivity.

Humans evolved to make sense of things. Every time a stimulus comes to us, our brain does the efficient thing: It responds based on past experience. In so doing, the brain continually redefines normality. It is being shaped, literally, as a consequence of trial and error.

“The brain did not evolve to see the world the way it really is—we can’t,” Lotto says. “We can’t help but to see things according to history—our own history and that of our ancestors—because we are defined by ecology. Not by our biology, not by our DNA, but by our history of interactions.”

Sensory information can mean just about anything, Lotto observes. It’s what we do with that information that matters.

When context distorts

Society gets inside of our heads and habits, says Ruha Benjamin, professor of sociology and African-American studies at Boston University.

“It forms everything from our taste in food, our sensibilities, what we think is good, bad or evil. None of these beliefs occur in isolation.”

This profound social influence, known as “habitus,” is acquired through activities and experiences of everyday life, and is often taken for granted. The concept hails as far back as Aristotle.

Quite often relying unconsciously on habitus for context serves us well.

Until it doesn’t.

The beginning of awareness

According to Lotto, the creation of all new perceptions begins in the same way, with a single question: “Why?”

“Why” is, in that sense, the most dangerous word in history, Lotto observes. Because as soon as you ask that question, you open up the possibility of change. So asking “why” may be the hardest thing for people to do.

Education must be about creating new perceptions, Lotto says. Traditionally education has been about efficiency—it wants to know what happens at the end. There is a right answer. But people really need to learn to move between the “why” and the “how.”

Innovation and change are, at their very essence, a “why” proposition, says Jennifer Mueller, a psychologist and Wharton management professor who studies creativity. The “how” comes later.

It’s in this way that perception becomes the gateway to innovation and change.

“People are so averse to uncertainty that they can’t see creativity. They are blind to it,” Mueller notes. But by becoming aware of our mind-sets and perceptions, we can step in the direction of breakthroughs.

The power to choose a response

There are practical ways to start on the path to growth and innovation.

You must at the outset be certain that you want change, Mueller says. “Be clear strategically whether you really are looking for something groundbreaking. Define what that means. Sometimes people call something innovation, but it really isn’t.”

Lotto says that the aim of his research is to help people transform by enabling them to understand and become part of learning about their own perceptions.

“I hope people will walk away from my experiments, not with an understanding of color, but an understanding of themselves, or at least a question of themselves.”

The first step, he says, is awareness.

“You must see yourself see. It’s about observation and curiosity, having a sense of wonder, becoming aware of the connection between the past and the present. Becoming an observer of yourself enables you to do amazing things.” .

Excerpt Amanda Enayati