Now, a big caveat: That big October drop in participation could have been skewed slightly by the government shutdown. The official household survey counted 720,000 people as leaving the labor force in October, but that might have included some furloughed federal employees or contractors who have since returned to the job. If so, expect a small rebound.

But even setting that aside, the longer-trend has been downward. Back in September before the shutdown hit, the U.S. labor force participation rate stood at 63.2 percent–also the lowest since 1978.

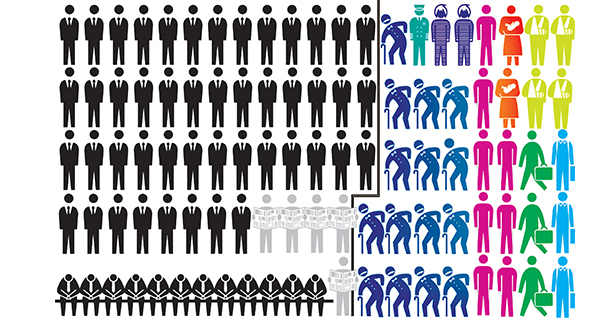

So what’s up with that broader trend? Why has the participation rate been dropping? There are a couple big factors going on here. Older Americans are retiring, younger Americans are going back to school, and many workers have been discouraged by the weak U.S. economy.

The aging of America

Baby boomers are starting to retire en masse, which means that there are fewer eligible American workers.

Demographics have always played a bigrole in the rise and fall of the labor force. Between 1960 and 2000, the labor force in the U.S. surged from 59 percent to a peak of 67.3 percent. That was largely due to the fact that more women were entering the labor force while improvements in health and information technology allowed Americans to work more years.

But since 2000, the labor force rate has been declining steadily as the baby boom generation has been retiring. Because of this, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago expects the labor force participation rate to be lower in 2020 than it is today, regardless of how well the economy does.

Americans over the age of 65 are less likely to work than prime-age Americans. And since that subset of Americans is expanding its ranks, that drives the labor-force participation rate down. Note that this shift is happening even though older Americans are staying on the job for longer than they did during the 1990s.

Economists disagree, however, on exactly how much demographics are responsible for the fall in the participation rate. The Chicago Fed estimates that retirements accounted for only one-fourth of the drop in labor force participation since the recession began. Other analysts, including Barclays, have suggested that aging Boomers could account for a majority of the fall.

Bad economy

The bad economy is keeping workers in school and out of the labor force. Demographics can’t entirely explain of the labor force fall, however. For one, the number of Americans working or actively seeking work has actually fallen faster than demographers had predicted.

And here’s another clue that this isn’t just a demographic story. The participation rate for workers between ages 16 and 54 fell sharply during the recession and still hasn’t recovered. Obviously retirements can’t explain this.

So what’s going on? One theory is that the weak job market is causing people to simply give up looking for work–they’re crumpling up their resumes and going home. A recent paper from the Boston Fed suggested that these “non-inevitable dropouts” might account for the bulk of the decline.

Other analyses have put a different twist on that story. According to a recent paper from the Urban Institute, the rate at which people are leaving the labor force is actually lower than it was during the aftermath of the 2001 recession. That is, labor force drop-outs aren’t the big story here.

Instead, the Urban Institute notes, what’s happening is that workers aren’t entering the labor force at the same rates they used to. That’s especially true for women, who are much less likely to enter the labor force today than they were in 2002 and 2003. Many are enrolling in school instead or deciding to stay at home to raise the kids.

That’s not always a bad thing: The fraction of 16- to 24-year-olds pursuing an education has been growing over time, for instance. That could mean a more skilled workforce in future years (though it could also mean more young Americans weighed down by student debt).

But the economic story here is also bleak in places, particularly for older workers: Another recent paper noted that the decline in U.S. manufacturing jobs may be partly responsible for the fall in the participation rate. During the housing boom in the 2000s, many of those manufacturing workers were able to find new jobs in the construction sector. But once housing went bust, they were left adrift, unable to find new work.

Disability

More workers are going on disability insurance. There are now roughly 8.8 million Americans receiving disability benefits, a number that has doubled since 1995. Could that be a factor pulling people out of the labor force?

Possibly, although this is likely a smaller part of the story than the other two factors –the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland estimated in 2011 that changes in eligibility criteria for disability could account one-quarter of the fall in the participation rate between 2007 and 2010, or about 0.5 points.

The University of Chicago’s Harold Pollack has, however, cast doubt on the claim that the lure of disability benefits is taking workers out of the workforce: “One way to see this is to look at the employment rates for people who applied for disability but were then denied,” he said. “And those are actually quite low, below 50 percent. That suggests we’re not pulling people out of the workforce who would otherwise be there.”

So why does the size of the labor force matter? For one, if people are leaving the labor force for economic reasons (and they’re not going back to school), it would mean that the economy is in much worse shape than the official unemployment rate suggests. The jobless rate is officially 7.3 percent, but that only counts people who are actively seeking work–not labor-force dropouts.

The size of the labor force also goes a long way in determining America’s growth prospects. If, say, baby boomers are retiring faster than expected, then U.S. economic growth will be lower than projected.

Even worse, if discouraged workers are dropping out of the labor force entirely, they may never make their way back into jobs. Their skills erode over time. Companies don’t even bother to look at their resumes. They essentially become unemployable.

That’s a massive human tragedy. It could also mean the U.S. economy will be significantly weaker in future. One recent paper from the Federal Reserve estimated that America’s economic potential is now 7 percent lower than it was before the financial crisis–in part because workers who lost their jobs during the downturn have become less-attached to the labor force. That’s a bad sign.

As people drop out of the labor force, the nation’s underground economy appears to be growing. By some estimates, the informal “shadow economy” is now worth $2 trillion. Examples would be people working as consultants (in something like IT), drivers, people running small eBay (EBAY) businesses, nannies, and landscapers.

Author: Brad Plumer, washingtonpost.com