Housing affordability is an issue for a growing number of the nation’s 111.1 million renters, which include people living in housing from apartments to single-family homes. In fact, the number of cost-burdened renter households (those spending more than 30 percent of their incomes on rent) reached 23.4 million in 2015, with more than half (54 percent) qualifying as severely cost burdened, according to U.S. Census data.

For the multifamily industry, the heart of this issue is supply versus demand. Despite some significant jumps in multifamily construction activity, the total number of new units has only recently begun to meet annual demand. This imbalance inherently creates a scarcity that drives up apartment rental pricing.

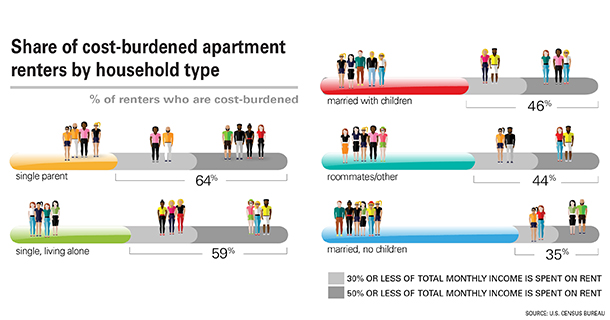

Moreover, rising development, materials, labor and operations costs also continue to provide upward rent pressure at the same time that stagnant incomes, increased student debt and rising healthcare costs are putting greater strains on apartment renter households of all shapes and sizes.

Having enough affordable apartment options is a key component to creating and growing healthy, vibrant communities across America. With this shortage of affordable apartments for low- and moderate-income households worsening, the nation’s challenge is to figure out how to expand the stock. But increasing the supply of apartments starts with getting more creative about how to finance the expansion.

Growing the stock

In normal economic times, the apartment industry needs to build between 300,000 and 400,000 new apartment homes annually to meet renter demand and account for losses to the stock from obsolescence, natural disasters and the like. After years of under producing, the industry finally ramped up production to fully meet that demand last year, delivering 310,300 new apartment units nationwide, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. While this increase in new production is largely positive for the industry and its affordability challenges, it’s only the first steps toward a distant goal.

The vast majority of the new apartment units coming on line are market rate rather than affordable to people at lower incomes, because that is the only product type that makes economic sense for the industry. Outside of the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program, which I’ll discuss more fully herein, it is virtually impossible to produce new apartment units ground up that are affordable to households at or below area median income. Why? The list of reasons is long, but the chief culprits are the cost of land, the cost of labor, long and costly entitlement processes, outdated zoning and land use policies and burdensome regulations governing new construction.

We also have a lot of apartments across the country that are housed in properties with 50 or fewer units. Nearly half (49 percent) of those properties are owned by individual owners versus larger private or public companies. For them, the apartment rental business is very good—virtually no vacancies, often waiting lists to rent and very competitive returns—so there is little incentive to consider repositioning units, much less properties, for affordable purposes.

And our stock is old and getting older. According to the latest Census data, 51 percent of the apartment stock in existence today was built before 1980; that figure jumps to 82 percent when you look at how much was built before 2000. Moreover, it’s estimated that the industry loses as many as 125,000 units a year to obsolescence, among a variety of other factors. Given that older units not only comprise an increasing proportion of the total apartment stock but also serve as the primary source of the nation’s more affordable housing, we must also take care to preserve and rehabilitate older units.

Expanding the stack

But all these activities require stable, consistent sources of financing, which can be at odds with an affordable multifamily housing system that is both nuanced and complicated. Our industry needs to support the participation of capital that is already in the affordable market while finding ways to encourage new players to invest.

The LIHTC program is by far the most successful affordable housing finance program, supporting the production and rehabilitation of more than 90,000 units annually. Outside of direct subsidy programs, it is also the most viable means of providing housing for people at 60 percent of area median income or below—which are often the people struggling most with housing costs. And the program does all this with $8 billion in annual funding—a veritable rounding error in the nation’s budget. For this reason, our industry should be pushing lawmakers for at least a 50 percent increase in LIHTC funding to expand what is already a proven means for producing truly affordable new units.

We also need to change the capital stack that developers can access to fund affordable housing work. The LIHTC program gives developers a low cost of equity that helps them achieve lower rents while still hitting threshold returns. We need to figure out how to partner with new sources of equity capital to replicate the benefits inherent in the LIHTC program.

One untapped source of funding are foundations, which make grants to nonprofits to promote a variety of outcomes to benefit society and populations at risk. Why can’t they pool some of their grant funds into a comingled equity fund for developers to tap exclusively to achieve more affordable rents in their developments? As opposed to the many types of grant making where it’s difficult to measure outcomes, it would be very easy to connect the dots between a foundation-supported equity fund and the number of households able to reduce their rent burdens via units more affordable to their incomes.

Moreover, foundations are keenly focused on preserving capital in their investments from endowed corpus, but not every investment needs to meet maximum threshold returns. If that’s the case, why can’t they earmark a small portion for social investments in the affordable housing space that carry positive, but below-market returns?

Municipalities and businesses can play important roles, too. Cities, for example, have several tools at their disposal, from ownership of land and buildings to taxing authorities, and they should use their toolboxes to help nonprofits better compete for buildings they pledge to maintain in the affordable space for long periods.

Local businesses also should have a stake. As employers, they need to attract and retain the best talent possible; they lose out when employees must live remotely and endure lengthy and expensive commutes for their jobs. We need to be creative in what we ask employers to do to help assure an adequate supply of units affordable to all income ranges. In short, employers need to invest in their communities a little differently going forward to help ensure that those communities remain healthy and vibrant.

With demand for more affordable housing growing, both becoming more acute for the lowest income earners and spreading to affect more households struggling under other rising costs, we, as a nation and an industry, need to be proactive in our response. Because without adequate affordable housing, our communities and businesses miss out on the critical human resources and every day economic activity they need to grow and prosper. But growing the stock of affordable apartments has to start with expanding the financing opportunities available to support the production of these units. And therein lies the greatest challenge—but not necessarily an insurmountable one.