As a segment of the growing senior population seeks upscale urban living, an affordability crisis looms.

Michael Gordon, VP of planning and development for a Boston real estate firm, has been counting down the days until a new high-end apartment and condo complex opens. The 92-unit projects boasts the kinds of amenities common in the current spree of high-end rentals going up in American cities: walk-in closets, full kitchens, more spacious layouts, numerous communal areas, concierge services, chauffeured car service, even an on-site movie theatre and two restaurants.

The key difference between Waterstone at the Circle and other expensive high-rises is the demographic of its clientele. The average move-in age of future Waterstone residents is 82.

“We’ve found that most seniors want to remain in the city,” Gordon says. “You’re seeing a trend where empty-nesters are downsizing and lots of new product are being built for them. They’ll want additional services when they’re 80.”

Opening in Boston’s Brighton neighborhood in January, Waterstone, which is being billed as an urban independent living community, represents a watershed in American demographics, senior life, and real estate development. Gordon’s firm Epoch Senior Living has made a big bet—he wouldn’t specify how much the building costs, but with rent starting at $7,000 a month, it’s safe to assume it’s quite a bit—that baby boomers’ golden years will be a golden opportunity (it already opened a similar project in Wellesley). As Americans live longer with more healthy, active lifestyles, senior housing is being rethought, redesigned, and, in this case, rebranded.

“They want walkability,” Gordon says of similar clients in other Epoch properties. “Go to their units at 3 in the afternoon and they’re empty. People are out and about. This is all about high-end, independent living.”

Waterstone goes online before the coming wave of older Americans crests. Gordon says many residents, at opening, will actually be the parents of younger baby boomers. Since the average baby boomer doesn’t turn 80 until 2026, the real growth in this market won’t occur for another decade.

The active, wealthy senior may be the new millennial

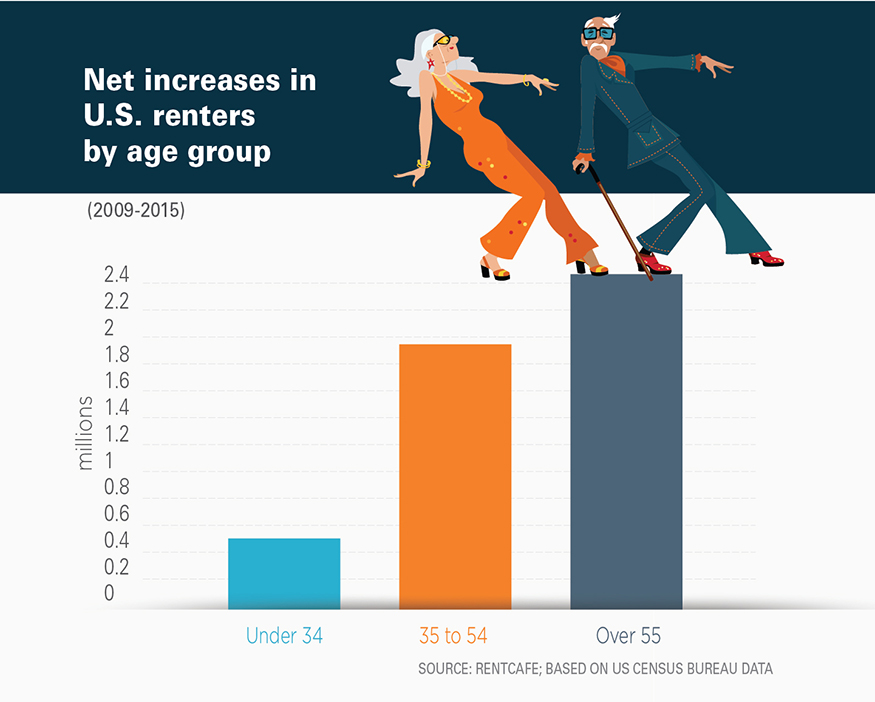

The number of senior renters has grown dramatically across all income levels—not just the high end of the market represented by Waterstone. According to a new analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data by RENTCafe, they’re actually the fastest growing segment of the country’s rental population.

Between 2009 and 2015, the number of renters over 55 increased by 28 percent, compared to a 3 percent increase in renters 34 years or younger. Clearly, there are already a lot more younger people living in apartments. But the significant jump in seniors, representing 2.5 million more 55-plus renters, comes before the so-called “silver tsunami” hits, suggesting both lifestyle and demographic shifts are at play.

The study’s author, Nadia Balint, says the data points to rapid growth in highly educated, empty-nest baby boomers, driven by a number of factors: lifestyle changes, lingering financial challenges from the 2008 housing crash, and an inability to trade down in the ownership market due to a lack of affordable options.

“They were forced to downsize, or they’re simply finding out renting is a better choice for them at this point in their life,” says Balint. “But there are also more rental options on the market that appeal to this demographic, more mixed-use developments in suburban downtowns and transit oriented locations. They offer a more manageable, flexible lifestyle with fewer maintenance costs.”

Balint’s data show the 55-plus renter population has grown most quickly in the areas one may expect: warmer, urban parts of the Sun Belt. Tampa, Florida, saw a 61 percent jump between 2009 and 2015, Phoenix saw a 59 percent rise, and Dallas recorded a 46 percent jump. For developers, the active, wealthy senior may be the new millennial.

Waterstone and other projects like it are betting on this niche, but profitable, market of rich urban seniors over 80. In Manhattan, the $246 million Maplewood Senior Living residence, a 23-story luxury high-rise offering 215 units and a farm-to-table restaurant, is meant to be the first of a line of branded high-rises called Inspir. But as they age, plenty of active boomers will also seek out urban or urban-style living without the hassle or overhead of ownership.

Today’s young seniors “don’t want to feel like they are tucked away in some suburb,” Traci Bild, head of Bild & Co., a Tampa healthcare consulting firm, told the Wall Street Journal. “If you are getting that younger resident who is not 80 yet, that’s someone who is going to want that urban environment and pay for it.”

The Silver Tsunami and an aging U.S.

Population trends suggest developers should be figuring out how to break ground now. The population has significantly aged in just the last few decades: The average age was 28 in the 70s, says Balint, and today it is 37. According to Projections and Implications for Housing a Growing Population: Older Households 2015-2035, a 2016 report by the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, the number of Americans over 80 will double in the next two decades from 6 million to 12 million. Gordon says the average move-in age for a traditional senior rental property right now is 82.

One out of three U.S. households will be headed by someone over 65 by 2035. That’s 79 million Americans, many thinking of retirement—and renting—in a whole new light. The jump in the 80-plus population will be meteoric. This group will grow 18 percent between 2020 and 2025, and then rise a further 27 percent between 2025 and 2030.

Compare growth projections to the total stock of senior living units in the country, and it’s clear a building boom is needed. According to NIC MAP, a market data provider for the senior housing market, the current U.S. inventory breaks down as follows: 410,000 independent living units, 340,000 assisted living units, 85,000 memory care units offering services for those with Alzheimer’s and other conditions, and 150,000 skilled nursing care units providing round-the-clock care.

The market appears to be divided in a few different ways, with active lifestyle options for those 60 to 80 (witness the rise of themed retirement villages such as Margaritaville, which certainly aren’t selling a quiet, relaxed suburban lifestyle) and more assisted and supportive living for octogenarians and above. Balint says that many boomers looking for a more urban experience will seek out amenities designed to provide convenience and a comfortable place to live, offering opportunities for socializing so that residents can feel at home even though they’re renting. According to Jennifer Molinsky, a senior research assistant at the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, the percentage of senior renters making $60,000 a year or more rose from 11 to 15 percent between 2006 and 2016.

Welltower, a development firm working on its own high-end senior urban developments, conducted an Aging in Cities Survey earlier this year that captured what a very profitable segment of this population wants: 8 out of 10 baby boomers who live in a city want to remain in the city when they are 80-plus years old, with the same percentage expressing openness to urban senior living communities. They want a home that offers access to high-quality health care, a connection to public transportation, neighborhood walkability, and proximity to family.

Looming senior housing divide

But as developers begin building in anticipation of a new segment of wealthy customers, another segment of the growing senior population, low-income renters, should be inspiring similar action within local and national government. A report compiled by the Center for Real Estate at MIT puts it into perspective: While a few dozen cities may be attracting active seniors back downtown, “the general trend in the United States is still toward increased suburbanization of the elderly population,” the report states. “We will have to confront the real estate issues posed by a growing suburban elderly population for years to come.”

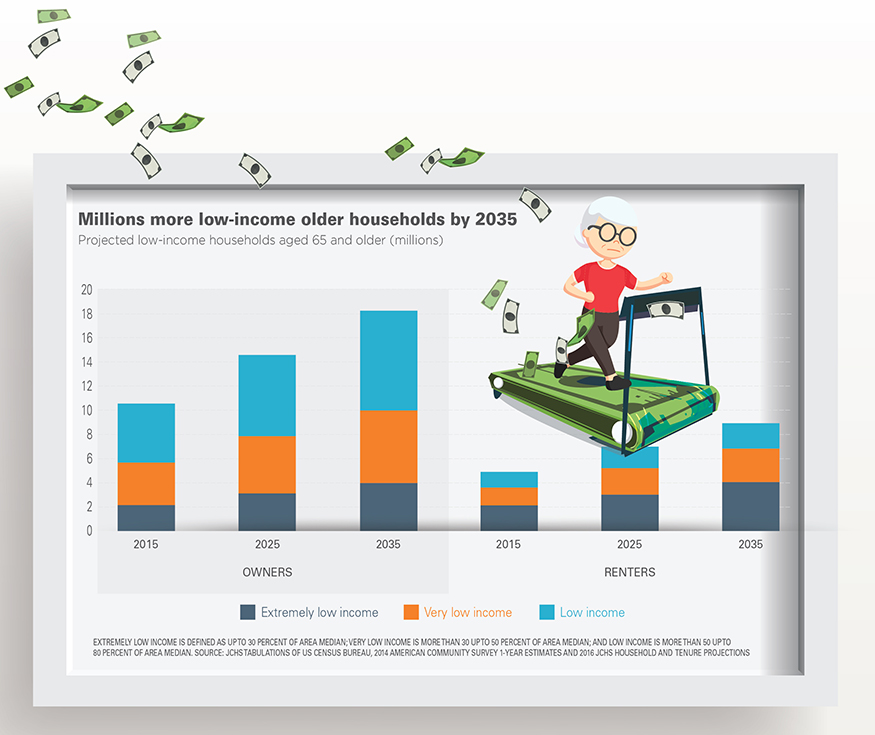

One of these issues is a lack of affordability. According to Molinsky, the U.S. only serves about a third of adults 62 or older who qualify for housing and rental assistance. If this paltry response rate doesn’t improve by 2035, nearly 5 million eligible seniors won’t receive much-needed housing aid. In its recent report on senior housing, the center predicted a “near doubling of low-income renters and owners, many of whom will face housing cost burdens.”

It’s not just the most vulnerable at risk. For one, savings patterns today suggest less wealth for tomorrow’s seniors. A recent study from the George Washington University School of Business that spoke with 5,000 pre-retirees between the ages of 51 and 61 found that 60 percent have at least one source of long-term debt (26 percent have more than one), 30 percent lack any retirement account, 36 percent couldn’t come up with $2,000 for an unexpected emergency, and 45 percent reported spending less than they are earning. Molinsky says more and more older adults are carrying a combination of consumer, student, and housing debt into retirement, and many who are just about to retire lost substantial household wealth due to the Great Recession. Stories about older Americans working later in life tend to omit that these are usually already high-paying, white-collar professions, she says.

These issues fuel some disappointing predictions by the Social Security Administration’s MINT model (Modeling Incomes in the Near Term). The share of retirees who will lack sufficient income at age 67 to maintain pre-retirement income will increase in the future, and get worse over time. For the leading boomers (born between 1946 and 1955), 39 percent will have inadequate income, as opposed to 35 percent now. That figures rises to 41 percent for trailing boomers (born 1956 to 1965), and to 43 percent among generation X members (born 1966 to 1975).

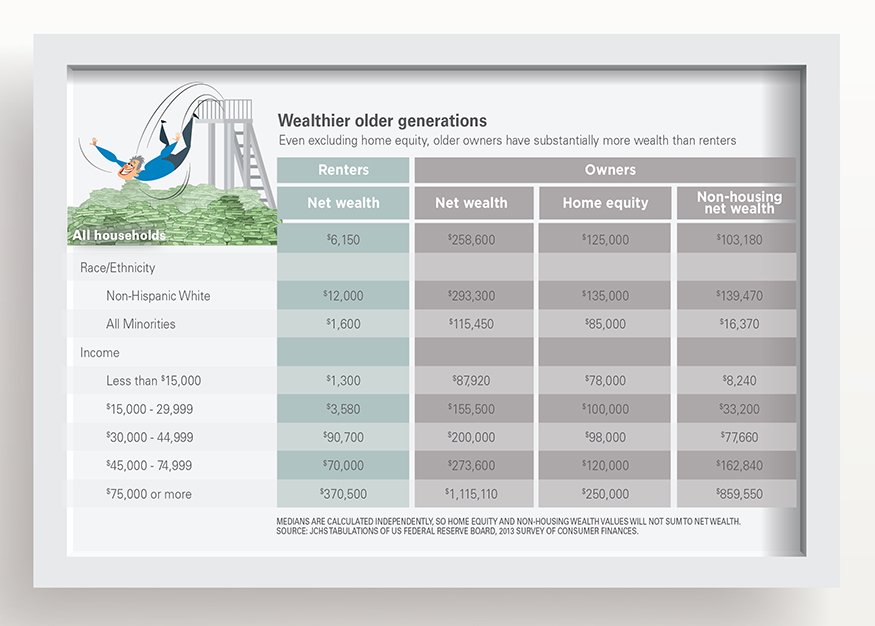

Cutting back may not be problematic for well-off households, but that gets very difficult for lower-income households. That’s even more pronounced when taking into account owner versus renter households, and white households versus households of color, at a time when rental rates are rising. According to Harvard data, among households headed by non-Hispanic whites aged 65 and over, median net wealth in 2013 was $260,700, almost quadruple that of households headed by a person of color of the same age ($68,000). And the typical older-owner household has 42 times more wealth than a renter household.

This may be the most troubling aspect of the future of senior housing: the widening gap, and the potential lack of a pipeline for lower-income renters. Developers like Epoch, catering to a wealthier demographic, will build more urban, transit-oriented homes for some of tomorrow’s older adults, offering a closer connection to the cities they know, the social lives they crave, and the families they love. But without more action, a much wider swath of the population may find the hunt for affordable, convenient housing more of a challenge. Molinsky says she’s seeing some movement to address the enormity of the challenge. A federal tax credit for aging in place has been proposed, and many cities are supporting tax credits for retrofitting homes and changing building codes to improve accessibility, both means to increase the amount of affordable, attainable housing.

“The whole issue of housing for older adults is an issue we’re just beginning to wake up to,” says Molinsky. “Helping older adults who can’t afford housing is one of the trickiest possible issues.”

Excerpt Patrick Sisson, Curbed