Instead of those conditions adding up to more babies, as they traditionally have, the U.S. birth rate dropped—and it’s not clear whether women today are simply delaying having children or choosing to forgo it altogether.

The answer to that question could have a far-reaching impact on the country, affecting future job markets and economic growth as well as social programs that provide for the elderly. It could change how families cope with aging relatives, experts say.

And because births to immigrants have historically bolstered America’s birth rate, immigration policies may be shaping that future, too.

In 2014, experts from the U.S. Census Bureau, Demographic Intelligence and other groups noted the economic recovery and predicted the U.S. birth rate would rise as a peak number of millennial women moved from their early to late 20s. That’s what history told them.

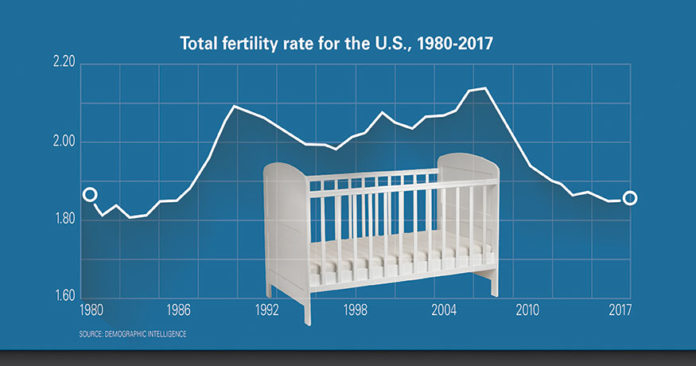

“We are seeing the opposite,” said Samuel Sturgeon, president of Demographic Intelligence (DI) and author of its U.S. Fertility Forecast. DI’s most recent forecast says births will have dropped about 2.8 percent by this year’s end to 3.84 million, compared to 2016’s 3.95 million. When 2017 actual births are counted, the total fertility rate in America will likely hit a 38-year low of 1.77 children per woman, well below the “replacement rate” of 2.01 children per woman.

DI expects actual births to fall short of predictions for 2017 by 210,000 babies— and from 2015 to 2017, 310,000 fewer babies than would have been predicted by traditional demographic models. The drop is being credited to fewer births to teens and women in their 20s. But it’s bucking expectations based on traditional factors like the economy and employment, and experts are scratching their heads, unsure why it’s happening and whether it’s a long-term trend.

Searching for reasons

One answer may lie in reported rates of sexual activity among young adults ages 18 to 25. In 2010-2012, 91 percent said they’d had sex in the last year; that fell to 78 percent between 2014-2016. Reported frequency of sex also declined, DI reported.

That shift is one of many theories regarding drivers of the decline in births being noted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and others. Abortions are down, so that’s not it. Contraception might account for some of the decline. But preliminary data from the General Social Survey suggests less sex itself may be more significant in the reduction.

Bradford Wilcox, senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies and a visiting scholar for American Enterprise Institute, cited a recent Pew Research Center study on reduced sexual activity as he wondered if “declines in young adult relationships and sex are playing an important role in ongoing declines in births. It seems like young adults are more hesitant to or less able to move into relationships today, even net of economic factors.”

Or maybe San Diego State University psychologist Jean Twenge’s research has it right, and it’s the rise of smartphones and social media “fueling the relational disconnect we’re seeing among today’s young adults,” Wilcox added.

The share of young adults with smartphones has risen from around two-thirds in 2012 to 98 percent today

Unexpected impacts

Experts are just as unsure about the future effects of falling birth rates as they are about the causes.

“It’s a mixed bag. On the one hand, I think we’re going to see the rate of non-marital childbearing fall, since declines in births are concentrated among less educated, unmarried women. On the other hand, we also may end up seeing more women ending up involuntarily childless,” Wilcox said.

American expectation has always been “that bigger, wealthier generations are coming up behind the current generation,” Sturgeon said. “This may be a kind of day of reckoning. We don’t have bigger, and if it continues as it is, we won’t have wealthier. It might be a resetting of how we operate. Current data suggest that millennials are not doing as well economically as their parents at the same age.”

Excerpt Lois M. Collins, Deseret News