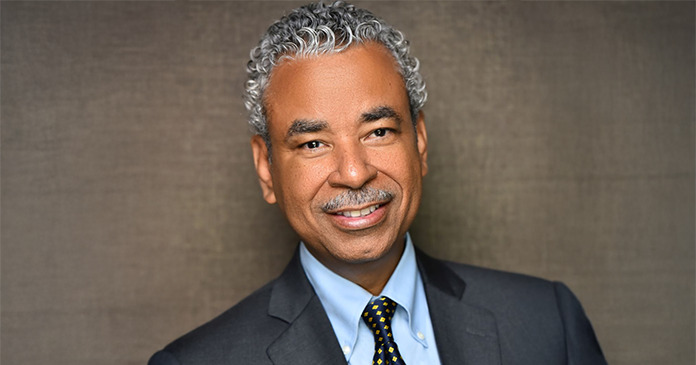

The term was coined by the Lebanese-American author Nassim Nicholas Taleb, a rather colorful, sometimes controversial theorist and author who became prominent for his 2007 book The Black Swan. Taleb is currently Distinguished Professor of Risk Engineering at New York University. No mere academic, Taleb made a fortune as a derivatives trader, applying his own theories to profitable results.

In his book Taleb argued that our lives are deeply shaped by relatively rare, mostly unpredictable events: financial crises, natural disasters, and other chaotic disruptions. (And some rare positive events too.) By definition, these events are not predictable as specific occurrences—but they are predictable as general phenomena, for which we can prepare and even benefit. Specifically, we can prepare for the inevitable occurrence of such unpredictable events by developing structures that, when these events occur, tend to “have more upside than downside.”

For Taleb, the essence of “robustness” (or resilience) is that we have structures that can withstand these “Black Swan” events when they are damaging. For example, the 2011 Japanese tsunami revealed that the Fukushima nuclear reactors were not robust; they were in fact “fragile.”

By contrast, Taleb uses the term “antifragile” to describe structures that not only withstand such events, but gain benefits from them. Taleb points out (in his 2012 book Antifragile: Things that Gain from Disorder) that this characteristic is everywhere in nature, and especially in biological systems. Muscles endure the strain and damage of exercise, and actually become stronger. The body gets infected with a small dose of an infectious agent and develops immunity. Indeed, evolution itself, as a cumulative process, relies on this “antifragility.” By contrast, insulating these systems from shocks actually makes them weaker over time—lack of exercise, or lack of exposure to immunity-generating pathogens.

Key to this antifragility is the ability to fail in small doses, and to use that failure to “gain from disorder” over time—paradoxically producing a greater order. Muscles get very small tears and strains, resulting in strengthening; a few cells get infections and die, but not before sending out markers that identify the invaders to many other cells. So keeping things “small enough to fail” (as opposed to “too big to fail”) is key. So is the ability to transmit lessons from these small failures, so that the structure can develop new strengths.

The failure of too big to fail

But getting “too big to fail” is precisely what’s going on in too many places today. The 2008 financial crisis, and its “too big to fail” banks, was a case in point. Modernity, Taleb says, is dominated by a culture of specialists who are rewarded for excessive intervention, and for predictions that are routinely inaccurate. The big reward for them is not in creating antifragility or even resilience, but stability—or rather, the temporary appearance of stability. Then, when disaster strikes, these specialists, who have very little “skin in the game,” pay a very small price, if any.

The result of this dynamic is that there is very little learning within the system, and we go right back to making structures that are more unstable over time. In evolutionary terms, we are not advancing into greater resilience, but lesser resilience.

Thus, instead of creating a world in which the most destructive Black Swans are more survivable, all the emphasis is on preventing such Black Swans, and creating an unsustainable state of normality. The inevitable result is that these Black Swans come anyway—with ever more catastrophic results.

Engineered vs. ecological resilience

A forest ecosystem provides a good illustration of Taleb’s point. Often there are numerous small fires that play key roles in the health of the ecosystem, taking out undergrowth, allowing new species to thrive, and consuming fuel before it accumulates to dangerous levels. But the “modern” practice up until recent times has been to suppress the fires—and of course, the result has been that the fires come eventually anyway, and then they’re much bigger and more catastrophic.

There is a relation to resilience theorist C.S. Holling’s distinction between “engineered resilience” and “ecological resilience.” The Fukushima reactor did indeed have resilience, but only up to a specific engineered point that was able to be anticipated by its designers. But a rare “black swan” event (the 2011 tsunami) exceeded those specifications, and the result was a catastrophe. By comparison, a forest ecosystem has a more robust form of “ecological resilience” that emerges and in effect “learns” from stresses to its ecological system—but only if those stresses are allowed to do their work.

For Taleb, there is an obvious corollary in economics. The more we suppress economic volatility, and the more we inject cheap credit (and debt) into the system to prop things up—and especially, the more we let institutions get “too big to fail,” effectively socializing risk and privatizing profit—then the more we are setting ourselves up for a kind of global Ponzi scheme that is bound to collapse, even more disastrously than before. Taleb thinks 2008 was such a collapse—in fact he made millions anticipating it—and he thinks we are now headed to an even bigger global collapse.

More broadly, Taleb sees a potential collapse of a range of human systems, under the management of their tunnel-visioned specialist-planners. They are not trained by failure, have no “skin in the game,” think reductively from the wrong models, and are biased toward intervention to prevent black swans rather than prepare systemically for them. The examples he cites take up much of the book, including cases from medicine, economics and politics.

There are obvious lessons for planning and architecture too. The promoters of this kind of planning are what he calls “fragilistas,” making strategic plans to avoid Black Swans instead of assuring that the Black Swans are smaller and more survivable—and even beneficial, as the result of their evolutionary process. The dominance of fragilistas across many disciplines is symptomatic of modernity, a problematic era of “humans’ large-scale domination of the environment, the systematic smoothing of the world’s jaggedness, and the stifling of volatility and stressors.”

The nature of architecture

There is a short but entertaining section on architecture specifically. “We are punished with the results of neophilia” in cities, he says. “The problem with modernistic and functional architecture is that it is not fragile enough to break physically, so these buildings stick out just to torture our consciousness.” By contrast, the “improved caverns” of traditional environments offer “fractal richness” that he finds makes him feel at home.

I would take that line of reasoning farther, and consider traditional cities and buildings as embodiments of “ecological resilience”—or of antifragility—with a remarkable complexity and durability. By comparison, our large-scale engineered and artistically packaged buildings are remarkably fragile, and in effect “throwaway” structures. Yet we have the hubris to suppose that these stripped-down bits of packaged engineering are somehow more “modern” than the more complex, more fine-grained, more beautiful and more sustainable buildings—the ones that have in fact sustained—to which we fragilistas are encouraged to turn up our noses.

Taleb points out, as Jane Jacobs did throughout her career, that our “modern” model of planning and design is fundamentally broken, and worse, demonstrably incapable of learning from its mistakes. We try to “plan” in a rational, linear, predictive sense, and the inevitable result is spectacular failure. Indeed, most of what passes for such planning today is pseudo-science, bureaucratic turf-building, and fragile clutter. The result is that it makes our entire civilization more fragile.

Learning from nature

What we can do, Taleb says, is to learn from nature, and develop structures and processes that can evolve and get smarter. Intelligence is not just in the individual, or in the individual’s planning or design, but in the overall evolutionary processes that we adopt. (And in the historic patterns that they embody.) That’s why real-world experience is much more valuable than theory: it can evolve, whereas theory is mostly a static rational process of deduction, translated into rigid enforcement of policies. It is fragile, and it breaks too often. When it does break, there is very little learning, and the system often goes back to the same prone-to-fail modes. When it doesn’t break, it only forestalls an even larger kind of collapse. This is where humanity is headed, he thinks, if we don’t adopt major systemic reforms.

To be sure, Taleb says, theory is important—if it’s philosophical theory about useful decision-making. “Wisdom in decision-making is vastly more important—not just practically, but philosophically—than knowledge.” That’s essentially what Taleb is sharing in his books—a theory of how nature works, and how we had better work too, if we want to survive.

Some will note the similarity to Jane Jacobs’ last book Dark Age Ahead, and to the idea that we need another kind of planning entirely, and another kind of design. We need a design for the process more than the product, and a “design for self-organization.”

Again, there are implications for the embodied wisdom of traditional patterns and practices, which now appear as evolutionary processes that confer antifragility. His description appears remarkably close to what Andres and Douglas Duany call the “vernacular mind”—the collective skill in producing beautiful and well-adapted habitat, which is evident throughout human history.

We need to embrace and empower such a capacity, surely—instead of regarding its genetic treasury as a modern design taboo.

Moreover, we need to embrace a different kind of design, and a different kind of planning—less about designing or planning the product, and more about designing the best, most antifragile possible process, incorporating the best genetic material, and getting the obstacles out of the way.

This is the best way—perhaps the only way—to assure that the result is stronger, smarter, better.

Author: Michael Mehaffy, Ph.D. is an urban designer, consultant, and senior researcher at the Ax:son Johnson Foundation in Stockholm.