The amenities arms race. That is what the real estate industry loves to call the escalating level of services offered by apartment buildings. For decades in the country’s hottest luxury rental markets, property owners have been investing outside of their units, providing all kinds of high-end facilities and high-touch services.

In these competitive markets, gyms become closer to fitness clubs than weight rooms, doormen are more like concierge than security, and common areas more closely resemble private lounges than they do motel lobbies.

The term arms race has a “keeping-up-with-the-Joneses” feel to it. It implies that the only reason some buildings are paying for these improvements is so they can compete with other, substitutable properties. It is true that there is a bit of bluster to many building perks. The delta between the amount people who sign a lease because of the gym and the amount of people who actually use it is well known in the industry.

Competitive versus loved

Amenities are just as much a part of the marketing budget as they are an operating expense. But the “arms race” thinking understates the importance of creating a connection with the resident.

In order to improve the way people connect with their buildings, many properties focus their amenity spend not on the spaces themselves. How can they be used to create a community? Creating a connection with the property is best done by creating a connection with the other people living in it.

Everything from community managers to communication apps have been deployed to connect residents of buildings and try, hard as it may be, to get them to engage with one another and meet in person.

Creating a community in a building was already a difficult task but it was made much more challenging when COVID hit and everything communal became off-limits. Connecting neighbors now must be done without residents sharing the same room. This has refocused the amenities arms race and led many properties to explore how they were able to fit into their residents’ digital world just like they had been trying with their physical one.

Window to the world

The coronavirus has confined so much more of our lives to our homes. When it comes to consumption we are limited to what can be delivered to us. Everything from groceries to entertainment to daycare is being delivered, streamed and relocated directly to our living quarters.

This has put the property industry in a unique position as the gatekeeper of much of our daily spending. The convenience and security that comes with deliveries quickly evaporate if the deliveries can not be brought into our buildings or our homes.

I spoke with Marcela Sapone, co-founder of Hello Alfred, a company that brings in-home services to urban residential buildings. Each building that they service has dedicated assistants who help residents with chores like laundry service and grocery shopping. Their in-home grocery delivery has obviously seen a lot of traction during the pandemic.

“We saw a lot of buildings stop deliveries to help keep their residents safe,” Sapone said, “We have the same people working at each building so it is much safer to have them deliver goods to people’s doors than a constant stream of delivery people.”

Sapone has a vision for her company that goes much further than just domestic services, “we are not a laundry company or a grocery company, we are a consumer company,” she said. “We want to become a distribution platform for the building itself.”

Hello Alfred coaches their “Alfreds” (a homage to the unsung butler in the Batman comics) to get to know residents on a personal level, recommending products and helping them with the small domicile details that always seem to be popping up in a busy household.

Gotta eat

With restaurants closing (and then re-opening and then closing again) across the country, one of the biggest growth markets right now is food delivery. Apps like Uber Eats and Doordash have seen a tremendous spike in activity now that people are not able to get a table at their local restaurant.

But the convenience of having your favorite meal delivered hot to your door has its costs, the brunt of which is borne by the restaurants themselves.

Delivery apps usually charge somewhere around 30 percent to businesses that are already struggling to stay afloat. There are also environmental impacts to be considered. Driving every meal individually across town has major impact on each bite’s carbon footprint, among other things.

To help alleviate these negative externalities of meal delivery, a few startups are offering dedicated catering services for residential buildings, similar to what existed in the office sector.

“Giving residents an easy way to order meals leverages purchasing power and network effects, while also helping local businesses,” said Everett Lynn, co-founder of Amenify, a marketplace that staffs the property with local professionals for cleaning, pet care, and other in-home services. He also thinks that the amount of waste produced by single orders is what ultimately breaks the food delivery model. By giving buildings a way to connect residents with local businesses, technology has created a new way for building managers to curate experiences and monetize their communities.

If our buildings become the conduit by which we find and buy new products, it will completely change the consumer equation. “You are going to see companies paying to promote their brands to residents,” predicted Devin Wirt, CEO of TFLiving, a technology-enabled amenities platform providing wellness and lifestyle services to residential and corporate locations across the U.S.

“I can see coffee companies willing to pay to put their brand in lobbies or alcohol companies sponsoring rooftops events in the near future. My belief is that these vendors will go through the amenity providers that are servicing the building as they will be the ones that connect the local and large scale vendors to the community.”

Landlords have long been expanding their service offering to include much more than just rental space. This has worked for utilities like WiFi internet and services like dog walking but, so far, buildings have had a harder time selling more personalized products to their captive audience.

Over the last few months residents have been more captive than ever which has helped change the way we think about our buildings from a place to rent space to a connection point for our consumption.

Communities come home

We have lost the ability to gather, one of the most fundamental of human endeavors. No matter how long we are forced to self-isolate, the desire to connect will always be inherent within us.

How can buildings create a community when people are not able to meet in person? One of the innovators tackling this is Ben Pleat, co-founder of a community engagement platform for residential buildings called Cobu. He first pointed out that strictly focusing on the amenities was never the right strategy, “It isn’t an amenity arms race, it is an experience arms race,” he said.

The challenge now is to bring experiences directly to us. Cobu does this with a combination of digital and in-person experiences. The pandemic has obviously put a heavier near term emphasis on digital engagement.

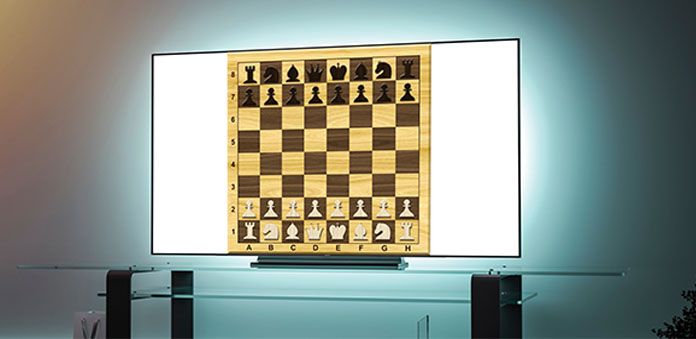

Pleat said Cobu saw a 130 percent increase in activity from residents as COVID hit, with residents facilitating digital meetups that have ranged from Bollywood dance lessons to board game tournaments via Zoom. “It isn’t just filling time, it is a human connection,” Pleat said. “We encourage people to put their video on.” He warns that creating a community isn’t the same as just providing entertainment. “The level of authenticity needed has heightened,” he said. “When you are doing things digitally, you are competing with Netflix so you have to really try hard to get people’s attention.”

To do this Cobu has virtual community managers who help promote digital activities. Although he very much has a “tech founder” mentality, he recognizes that software alone is not enough for creating human connection. Virtual community managers curate topics for discussion and spur engagement with helpful nudges. Pleat has already seen the importance of live content, “Having people interact in real time creates a bond,” he said. “Pre-recorded content is great to kill time but it doesn’t build community.”

Shifting community building online has changed the makeup of who participates. It empowers “introverts” to engage who might not have otherwise. “Many of the residents who never attended a live event are now power users of our digital experiences,” Pleat said. It has also created a way for people to connect before and after they are residents of the property. Pleat said he has seen residents begin engaging months before they even move in and often stay connected after temporarily leaving a building to be with family during COVID.

There is stickiness to community. Few things increase the chance of a lease extension like a resident having a friend at the property. Connecting residents in a meaningful way might not immediately show up on a company’s profit and loss statements but you could certainly make a case that it could be represented on its balance sheet in that most subjective of line items, goodwill. “Investing in community may cost more upfront and we might not see returns right away, but we know that the long term results in resident retention and satisfaction are worth it,” said Jessica Lee-Wen, director of marketing at the multifamily investment firm Upside Avenue.

Lee-Wen said that the focus on community investment came with a change in their organizational mission. “We always viewed ourselves as ‘value-add’ investor, but went through a big rebrand and we realized that this wasn’t just about building upgrades and new paint, it was about adding value to people’s lives,” she said. Interestingly, focusing on improving tenants’ lives also improved the organization itself. “The shift in mindset came hand in hand with a shift in company culture. It is increasingly important for people that they work for a company that has a social impact and we see that reflected in the quality and connectedness of our team members.”

Love thy neighbor

Creating a community in a building proves to be increasingly valuable to modern renters, but many forward-thinking building managers are starting to look at how to expand benefit to the entire neighborhood. Jonathan Andrews, development director at Twining Properties is working with his properties in downtown Boston. Since COVID hit they, much like many other buildings, had focused on online events that ranged from art classes to skull decoration for Cinco de Mayo to succulent gardening. But, he wanted to make sure that he was helping bring the neighboring community into his property rather than trying to replace it.

“We realized that many people moved to our properties because they are close to central business districts,” Andrews said. “When we saw how many businesses were closing and how many people were struggling we felt a sense of responsibility on some level.” So he has focused much of his resident experience programming on connecting with local businesses. They partnered with the creative consulting agency Isenberg Projects to bring in local artists to install art installations and have even streamed mixology lessons from popular local bartenders.

While there certainly is an altruistic component of supporting local businesses, this can also very much be a great strategic move for large properties. “People don’t move to buildings, they move to neighborhoods,” is how Warren Loy, Vice President at Lendlease so succinctly put it. His organization’s strategy revolves around developing properties that have spaces that can serve surrounding residents as well. Many of their developments include parks or, as is the case with their new development, Clippership Wharf in East Boston, a kayak launch. “We deeply believe that creating the best places includes ensuring our developments give back to the broader community,” Loy said. “It’s a strategy that is beneficial to our residents, our neighborhoods, and also to our business.”

Whereas most real estate teams spend their time analyzing comps to get an understanding of current valuation, developers like Lendlease take a longer view approach by finding ways to increase the future value. There is a certain tidal rise that happens to real estate prices when things start, dare I say it, gentrifying.

When areas start seeing a proliferation of new developments there are lots of implications for locals, not all of which are good. If more developers took Lendlease’s approach we might see much less resistance to infill developments like Clippership Wharf and Southbank in Chicago. NIMBYs would appreciate the appreciation that community placemaking would have on their property value and YIMBYs would be less concerned about exclusionary effects on less affluent residents. While these two groups have one of the widest political divides, it seems that the gap could be spanned with little more than good design, innovative management, and collectivist thinking.

Armistice

Competition is inherent in capitalism. Every consumer has a choice and so every product can be substituted for another. This has bred a combative element in our business world. But maybe this attitude doesn’t serve the property industry in the same way that it does consumer goods. Property prices are as connected to the community, both inside and outside of a building, as they are the specifics of the building itself.

Maybe now that buildings are starting to expand their offerings we should change the way we think about an amenities arms race altogether. Rather than focusing on the way building amenities compete we should consider how they can be accretive.

The property industry needs to understand that the benefits of how their buildings serve their residents and their neighbors can help raise the status of every property in the neighborhood, not just theirs. In a weird way, at a time when we are the most isolated, we are starting to see how interconnected we really are.

Excerpt Franco Faraudo is founder of Propmodo