Despite the chaos caused by the coronavirus, professional property managers are still getting rent checks from most resident.

It may be a sign of the times, but apartment experts are happy that most renters are still paying rent—for now.

It could be a lot worse. Millions lost jobs in the economic calamity caused by the coronavirus. Emergency programs that help many pay their rent are expiring—and not everyone who lost jobs benefited from these programs. It’s not clear how long renters who have lost income can continue to pay… and at many smaller apartment buildings renters have already stopped paying. But at larger, professionally-managed apartment communities, most renters continue to write checks.

“We continue to be pleasantly surprised,” says John Sebree, senior vice president and national director of Marcus & Millichap’s Multi Housing Division, working in the firm’s Chicago office. “In most parts of the country, most landlords are collecting most of their rent.”

Economy stalled by pandemic

The U.S. economy was still partly frozen as summer 2020 came to a close. Almost 11 million people filed continuing claims for unemployment September 26, 2020. That’s nearly half of the 25 million jobless people who filed continuing claims May 9, when much of the U.S. economy was still shut down to slow the spread of the virus. The unemployment rate of 7.9 percent in the month of September is also much better than its peak of 14.7 percent in April.

The number of renters who have fallen behind in their rent adds up to millions of people. Of the U.S. households that live in all types of rental housing units, one-in-six (16 percent) failed to pay their full rent in August. That’s nearly seven million households out of the 40 million counted in the Household Pulse Survey, week 14, from the U.S. Census. Of those 6.6 million households, one million believe they are likely to be evicted in the next two months. Many of those renters in trouble probably live in smaller apartment properties.

So far, the vast majority of people who live in larger, professionally-managed apartment communities continue to pay rent.

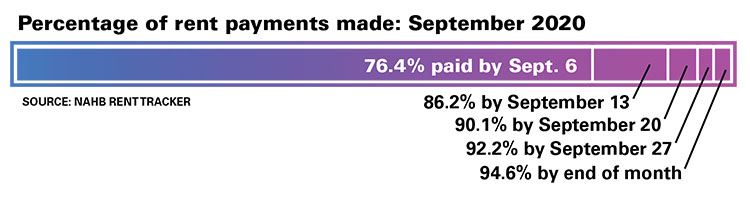

By September 27, more than nine-out-of-ten apartment renter households (92.2 percent) had made a full or partial payment for the month, according to the Rent Payment Tracker survey by the National Multifamily Housing Council (NMHC), which gathered data on 11.4 million professionally-managed apartments from five leading property management software systems. That’s more than half of the 21.4 million rental apartments in the U.S.

The share of households who paid rent in September 2020 is just a few percentage points less than the year before, before the coronavirus savaged the U.S. economy.

“Since unemployment super benefits expired in July, we have still seen a high level of rent collection,” says Ryan Davis chief operating officer at Witten Advisors, based in Dallas. “It is very encouraging.”

The renters who live in these professionally-managed properties typically had to show incomes substantially higher than their rental cost when they first signed a lease. Those who lost income in the crisis were probably able to access government programs, like enhanced unemployment benefits, while those benefit lasted.

“A piece of good news for owners of professionally-managed apartments is that residents by and large have stayed current on rent payments,” says RealPage’s Willett. “Those who can’t pay have tended to move out on their own, avoiding a run-up of debt. That pattern of behavior, which is consistent with what was seen in past recessions, suggests the eviction numbers will remain manageable.”

Property managers have carefully kept in touch with their residents to encourage them to pay more or less on time. “It hasn’t been without a huge amount of effort by landlords,” says Sebree. “They are calling tenants. They are working with tenants.”

When residents have lost income, many managers have accepted partial payments and helped renters arrange payment plans.

“We’re seeing more apartment operators work to find solutions to keep residents in their homes,” says Derek Merrill, CEO and co-founder of LeaseLock. “That dialog includes reminders of rent obligations and usually also offers of payment plans for those who perhaps can’t pay rent in full at the beginning of the month.”

Small community renters default

But millions of renters have already fallen behind in their rent, according to the data from the U.S. Census. Those renters probably live in smaller apartment properties.

“There could be more problems in small properties with ‘mom and pop’ ownership or in rental single-family homes,” says Willett. These smaller buildings are typically not included in surveys like NMHC’s Rent Payment Tracker. With just a few rental units each, they probably don’t use the expensive computer systems that report to the NMHC survey.

Of all the units of rental housing in the U.S., nearly a quarter are in relatively small apartment properties with just a handful of rental units. The renters tend to have relatively lower incomes, pay a lower rent and tend to work in industries more vulnerable to COVID-19, according to an analysis from the Urban Institute, a nonprofit research organization based in Washington, D.C. These renters may also include many who for one reason or another were unable to navigate the administrative challenges of claiming unemployment benefits.

“Small buildings with one to four units are doing the worst,” says David Dworkin, president and CEO of the National Housing Conference, based in Washington, D.C. “The renters have lower incomes and the landlords have fewer resources.”

The people who own these smaller rental properties tend to own just one or two buildings, according to the Urban Institute.

Many of these landlords have residents who are already falling behind in rent, according to a survey by the National Association of Hispanic Real Estate Professionals (NAHREP) and the University of California Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation.

More than half (52 percent) of the 380 owners and mangers who responded to the survey had at least one tenant who did not pay rent. The vast majority of these landlords manage fewer than 20 apartments. Among landlords who own between one and four units, a little less than half responded that rent collections have decreased, and close to 30 percent said that rent collections had decreased by more than 25 percent.

The owners of single-family rental houses may also be having problems with lost rent. There are 17.1 million single-family rental houses in the U.S. That’s more than a third of all the units of rental housing, according to the 2018 Rental Housing Finance Survey, from the U.S. Census.

A few hundred thousand of these rental houses are owned and professionally managed by big companies like Invitation Homes and American Homes 4 Rents. But the vast majority of these rental houses are owned by smaller investors who own just one property. They also tend to have fewer resources to continue to house renters if those renters have stopped paying rent, according to the Urban Institute.

Federal programs not replaced

Emergency programs created by the federal government have helped many renters continue to pay rent even if they have lost jobs and income. But many of these benefit programs have expired or are expiring, leaving the millions of people who lost jobs vulnerable as the crisis caused by the coronavirus stretches into winter.

“People are worried about it,” says Davis.

In the first weeks of the crisis, Congress created trillions of dollars of benefit programs through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (the CARES Act). That includes one-time, direct payments of $1,200 per taxpayer, though those checks were probably quickly cashed and spent in the first months of the crisis. It also created expanded unemployment benefits that provide an extra $600 per week. But those benefits expired at the end of July—leaving huge numbers of jobless renters vulnerable.

“There is a threat of a massive wave of evictions,” says Dworkin.

These renters received a temporary reprieve in early August, when President Trump created his own enhanced unemployment benefit by signing an executive order. His benefit provides recipients up to $400 per week in extra unemployment benefits.

By September, the majority of states had set up programs and were writing checks. But these funds would only last five to six weeks and are also running out. By the end of September, eight states including Arizona, Massachusetts and Texas had already distributed the money provided by the program, according the UnemploymentPUA.com, a website tracking the program. The rest of the states were only a few weeks away.

Even before the benefits expired, millions of workers were unable to claim them, according to an analysis by the Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy at New York University. Furman counts 1.1 million rental households in New York State with at least one member who lost employment due to COVID-19. But only about 800,000 of those households claimed unemployment benefits. That leaves hundreds of thousands of jobless people who didn’t collect unemployment benefits in New York State alone.

Some of these workers may have been paid in cash, so that they now cannot prove they had been employed before the crisis. Others may have challenges with their immigration status that keep them from getting unemployment benefits, even if they paid payroll taxes, according to Furman.

Moratoriums on evictions helpful

In the first months of the pandemic, many cities and states simply declared that property managers could not evict renters during the crisis. This web of eviction moratoriums also began to expire over the summer.

For a few weeks after these moratoriums expired in these towns, landlords filed evictions at a similar rate to typical year, despite broad agreement from apartment industry groups like NMHC that property managers should work with renters to avoid evictions whenever possible during the crisis caused by coronavirus.

Landlords have filed to evict 53,579 renter households since the start of the pandemic in the 17 cities tracked by the Eviction Lab at Princeton University.

On September 4, 2020, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a new order that protects renters from eviction through the end of 2020.

“This order could provide meaningful relief to families at risk of eviction and its devastating harms,” according to the Eviction Lab. However, the federal order does not provide rent relief to residents. When the moratorium ends at the end of the year, residents will be responsible for all unpaid rent that accrues during the moratorium, which could trigger a crisis of evictions then.

Households that suffer through an eviction often struggle for a long time afterward. They suffer lower household earnings, higher risk of homelessness and long-term residential instability, according to the New York Housing Conference. Evictions also increase family stress, emergency room use and school instability. After being evicted, some are also likely to squeeze into in overcrowded living conditions with family or friends that increase the risk of spreading the coronavirus.

However, an extended moratorium on evictions does nothing to help apartment owners who have to continue to keep their properties safe and warm for residents, even if those residents have stopped paying rent.

“Helping renters while putting apartment owners out of business is not in anyone’s interest,” says David Dworkin, president and CEO of the National Housing Conference.

Election stalls Congress

Another round of government assistance could prevent more renters from falling behind in their rent. But lawmakers seem unlikely to take action before the Presidential election in November 2020.

“Some federal government financial help for those who have lost their jobs certainly would help alleviate the pain that select renters are experiencing,” says Greg Willett, chief economist for RealPage, Inc. “But that’s certainly not something that either individual households or property owners are counting on.”

The U.S. Senate has declined to take action on the proposed, $3 trillion Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions (HEROES) Act, passed by the House of Representative in May. The proposal includes $100 billion in emergency rental assistance to help renters get current with their rent, in addition to a moratorium on evictions.

At the same time, Senate Democrats have blocked consideration of the $1 trillion HEALS act, which would provide supplemental unemployment benefits to those impacted by the shutdowns.

Apartment experts have repeatedly made the case to Congress for rental assistance.

“We should be doing everything we can to prevent evictions instead of waiting until they happen to respond,” says Brendan Cheney, director of policy for the New York Housing Conference, based in New York City. “It should be a no-brainer to protect residents and owners and the economy at the same time.”

Author Bendix Anderson