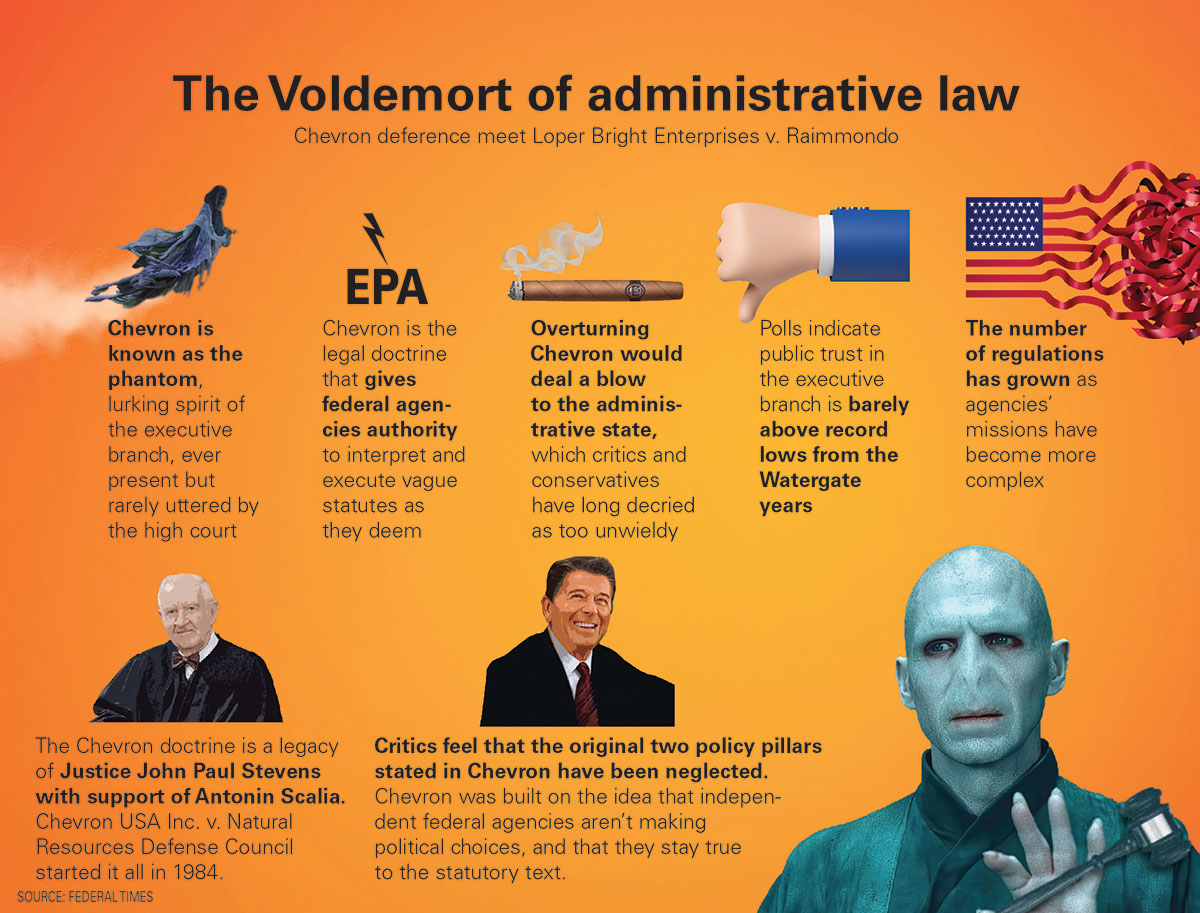

Limited-government advocates are urging the Supreme Court to overrule “Chevron deference,” a bureaucracy-empowering legal doctrine they say has distorted the U.S. system of government for decades at the expense of everyday citizens.

The court’s ruling could alter the current balance of power among Congress, executive agencies, and the nation’s judiciary by tearing away at the legal underpinnings of the modern administrative state, which critics deride as an illegitimate fourth branch of government.

In its landmark 1984 ruling in Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, the nation’s highest court held that courts “must give effect to the unambiguously expressed intent of Congress,” but where courts find that “Congress has not directly addressed the precise question at issue” and “the statute is silent or ambiguous with respect to the specific issue, the question for the court is whether the agency’s answer is based on a permissible construction of the statute.”

In other words, Chevron stands for the proposition that an executive agency’s interpretation of a statute is entitled to deference unless Congress has explicitly said otherwise.

Conservatives and Republican policymakers have long been critical of the doctrine, saying it gives unelected regulators far too much power to make policy by going beyond what Congress intended when it approved various laws. The authority of regulatory agencies has been increasingly questioned in recent years as the conservative majority on the Supreme Court has grown. Conservative Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Neil Gorsuch have expressed skepticism of the Chevron doctrine.

The America First Policy Institute is one of many public policy groups to file a friend-of-the-court brief in the pending Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo (court file 22-451) this month urging the Supreme Court to curb the doctrine.

The 1984 Chevron decision “violates the Constitution’s separation of powers, diminishes important checks on accountability, and produces a government less responsive to its people,” the group stated in its brief.

Curtailing the doctrine would “promote a return toward the diffusion of power the Framers crafted when they intentionally separated authority among our country’s three governmental branches.”

Adi Dynar is an attorney at the Pacific Legal Foundation, a public interest law firm that challenges government overreach and filed a friend-of-the-court brief in the pending case.

“For decades, Chevron has distorted our system of government. It puts a thumb on the scales of justice at the expense of American citizens facing federal agencies in courts,” Dynar said.

“Chevron flies in the face of the separation of powers by allowing agencies to usurp the legislative and judicial functions of the other branches of government. The court should undo this sorry mistake and end Chevron deference once and for all.”

The pain of bureaucratic fiat

The National Taxpayers Union wrote in its brief that the doctrine has led to abuses.

“Taxpayers know all too well the pain of bureaucratic fiat taking the place of proper legislation,” the brief reads.

“The IRS has a long history of regulating based on ‘silence’ in the Internal Revenue Code, despite the statutory frameworks’ famous level of detail and Congressional attention. When the tax laws are silent, but the IRS wishes to regulate anyway, then the taxpayers suffer—all because of Chevron’s allowance of ‘silence’ as a basis for agency action and judicial deference.”

The court decided on May 1 to hear Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo in its new term that begins in October. Loper Bright Enterprises is one of four petitioners in the case, all of which are family-owned companies active in the Atlantic herring fishing industry. The respondent, Gina Raimondo, is being sued in her official capacity as the U.S. secretary of commerce.

Liberal Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson has recused herself in the case, presumably because she heard arguments in the case when she was a member of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

In the case, the divided D.C. circuit court sided with the government, upholding a Department of Commerce rule that was questioned by fishing companies.

The rule requires the owners of vessels, which tend to be small, to pay for having federal observers onboard to oversee operations and ensure compliance with a host of federal regulations, the fishing companies said in their petition, which was brought with the assistance of the Cause of Action Institute.

The government mandate forces the fishermen in this case “to hand over 20 percent of their pay to third-party at-sea monitors they must bring on their boats—a mandate that Congress never approved by statute,” according to Cause of Action.

The petition stated that this “is an extraordinary imposition that few would tolerate on dry land.”

“But without any express statutory authorization, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) has decided to go one very large step further and require petitioners to pay the salaries of government-mandated monitors who take up valuable space on their vessels and oversee their operations,” the petition reads.

“That is truly remarkable, so much so that even the agency acknowledged that the power it asserted was highly controversial. In a country that values limited government and the separation of powers, such an extraordinary power should require the clearest of congressional grants.”

The government has misinterpreted the federal Magnuson–Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, which governs marine fisheries management in U.S. federal waters, to allow the “financially onerous… payment requirement” for domestic vessels “unburdened by statutory caps,” according to the petition.

The circuit court deferred to the government, determining that the statute was silent on the issue and that this is “either a fundamental overreading of Chevron or a powerful argument for its overruling,” the petition added.

The court may be ready to rein in the doctrine, according to The Wall Street Journal’s Supreme Court reporter, Jess Bravin.

There is “a lot of skepticism on this court” about the judgment of so-called expert agencies and whether they should be given deference by the courts regarding the statutes they have been charged to implement, Bravin said at a Heritage Foundation panel discussion on July 13.

“So I think we’ll continue to see doctrine emerging that may be reducing that type of deference going forward,” he said.

Source Matthew Vadum, Epoch Times