Offer a definitive explanation of the Ring Around the Rosie nursery rhyme and children’s game—whether as a reference to the Black Plague or teenagers ignoring bans against dancing and if you’re within earshot of a competent folklorist, chances are you’ll get an erudite slap-down.

No one knows for certain how it came about. (For example, the British version lagged the bubonic plague by some 700 years, according to the site HowStuffWorks.)

So, it seems only fair to add a more contemporary meaning: the vicious circle that comprises the apartment rental market in the U.S.

A cycle of rationalized cheap money from the Federal Reserve, a flood of investment in real estate like apartment buildings, and then hiked rents have reinforced one another, ultimately setting off an upward force on inflation and Fed-instituted interest rate hikes that ultimately helped keep inflation higher through rents.

How rents have jumped

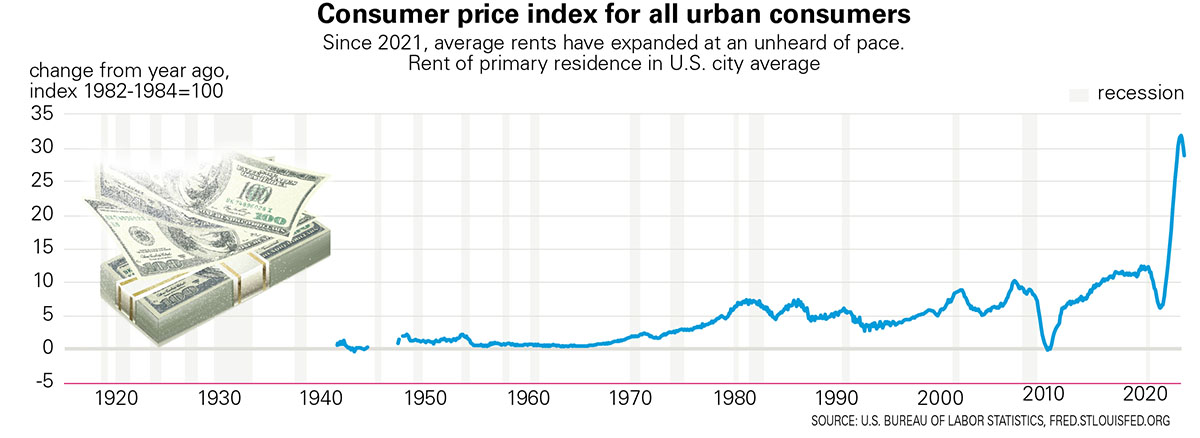

Let’s start with some background in the form of a graph of year-over-year percentage increases in the average rent of a primary residence. The data is from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and the graphical representation via FRED. The numbers are indexed to 1982-1984, which is given the value of 100. That allows a comparison of like measurements.

In general, rents would drop during a recession and begin growth again after. The more impact from a recession, the more rents dropped. At the high point of an economic cycle, landlords charged more, probably at least in part to cover previous losses of income during the down cycles, because while rents drop, mortgages don’t, and operating expenses may not.

Two periods on the graph stick out. The first is from mid-2010 through the end of the pre-pandemic. After that and the pandemic crash through May 2021, the year-over-year rise of average rents was astronomical.

Both can be laid at the feet of the Federal Reserve and monetary policy as a tool to “fix” the economy when politicians largely take fiscal measures off the table.

Great recession

Great recession

After the 2008 crash, within hindsight a Congress taking vastly inadequate measures, the response to a critically wounded economy was left to the Fed. They dropped interest rates in hope of sparking investment and job growth. But the Fed didn’t seem to realize that companies won’t invest if there’s no clear indication that demand is rising or could reasonably do so, based on observable trends.

Many companies and wealthy investors already had plenty of capital, didn’t see additional demand, and so the extra money went into activities like buybacks to push stock prices or putting more money into alternative investments, as low interest rates undercut traditional fixed income investments like bonds.

This period coincided with the growing interest of institutional investors in buying houses and renting them out, called the single-family rental market. It had existed before, largely in control of mom-and-pop investors—people who bought some extra homes for additional income. Now all of commercial real estate, including residential rental properties, caught big investor interest. It could provide higher returns than low fixed income yields.

The more money that enters an investment arena, the more asset prices in it rise. The investors bid them up. In real estate, as property prices increase, investors need to raise rents not just to cover annual expense growth, but to underwrite the entire investment plan. Rents go up.

Pandemic

Pandemic

Because financing was cheap through this period, there was actually some check on rent growth. Owners were making more, but there wasn’t the additional pressure for them to charge tenants even more than they were. That changed in the pandemic. Between Congress trying to keep many businesses afloat and the Fed pumping liquidity into the system to avoid the credit freeze-up of 2008, huge amounts of capital entered the hands of investors.

The money fueled an unparalleled surge of commercial real estate investment, especially with investors who had never paid much attention to the category before.

Interest rates were still cheap with high leverage in terms of the percentage of the property value that could be borrowed. Prices shot up and, as always happens in real estate, rents went up after the initial crash, but this time at an unheard of rate and degree.

The higher the prices and higher the rents, the more investors wants a piece of the action, which continues the upward drive of prices and, therefore, rents.

However, housing is roughly a third of the Consumer Price Index, more popularly known as inflation. As housing costs rapidly increased, so did inflation. After a long stretch of “nothing to worry about because it’s all temporary,” the Fed was forced to face significant inflation, so it did what it always does and tightened monetary policy — raising interest rates and reducing the number of mortgaged-backed securities they buy to help support the housing market.

As interest rates went up, so did the costs of financing property purchases or refinances, making the buildings more expensive to own. Which additionally pushed up rents to compensate. And while inflation growth has cooled, prices are still high. Even with rents coming up the recent pinnacle, they are still scaled up to a nose-bleed height.

This mechanism, driven by policy decisions assumed to be wise, is why renters are in such a tight squeeze.

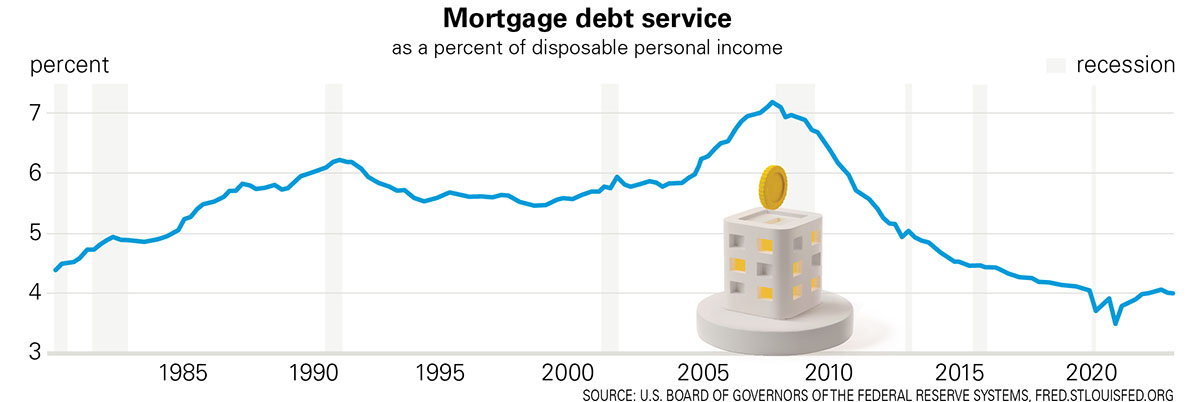

Now, to talk about home ownership, those who do are, on average, in much better shape. The following graph from the Federal Reserve via the St. Louis Fed, is of the percentage of disposable personal income (money after taxes) that monthly mortgage debt service represents.

This is an average and so doesn’t represent everyone. Some people have long-standing mortgages at lower rates or lower totals, which brings the average down. Those buying recently who missed the last of the 3-percent wave will probably be paying more. But, on the whole, this is why home ownership is so important to millions. It provides more predictability and stability.

Source Erik Sherman, Forbes