A new study reveals the depth of a problem that has plagued the U.S. for decades. While the number fluctuates, the latest academic research submits that the U.S. is short 15 million homes—not merely due to coastal regulations or urban planning failures, but because of a systemic collapse in the mechanism that helped build the American middle class.

According to research by Harvard University’s Edward Glaeser and the University of Pennsylvania’s Joseph Gyourko, if housing construction had continued at its 1980-2000 pace through 2020, the nation would have avoided the rent burden, displacement, and homelessness that now plague the nation.

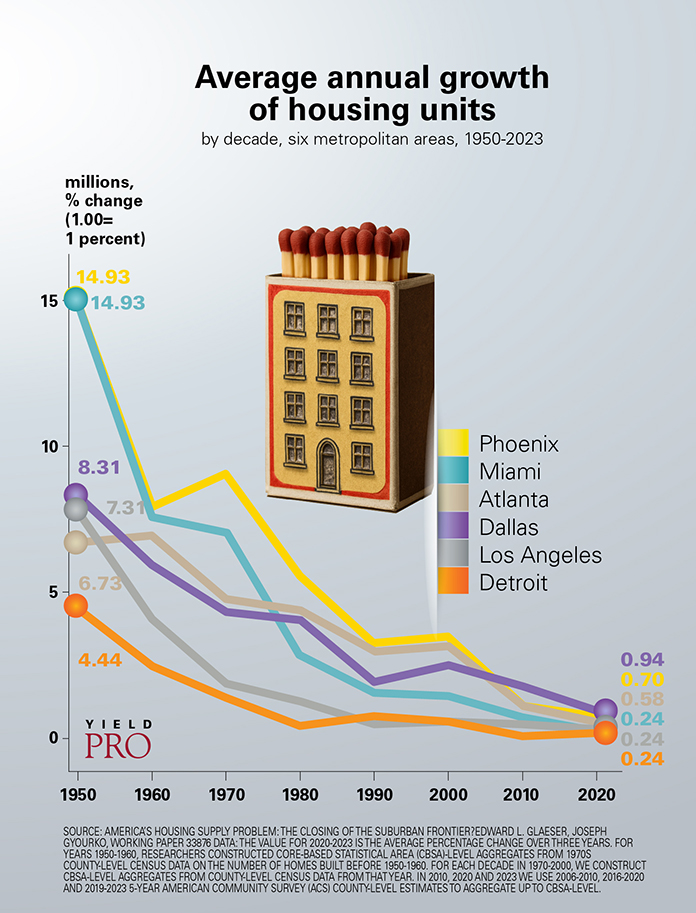

Instead, homebuilding ground to a halt precisely where it should have thrived: in the sprawling suburbs of Phoenix, Miami, Dallas and Atlanta—metros once celebrated as “building superstars.”

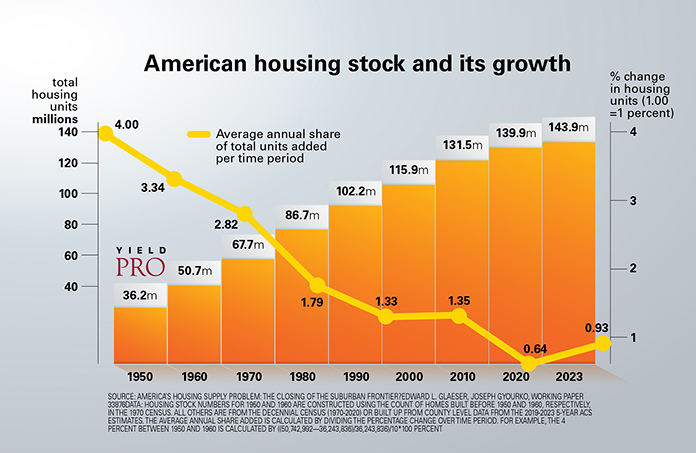

This is a stark reversal in American housing dynamics. From 1950 to 1980, metros added over 50 million homes as builders responded to rising prices with increased supply. The suburbs, aided by interstate highways and permissive zoning, absorbed millions of new households and their growing families. When demand surged, construction followed—a feedback loop that defined postwar prosperity.

This is a stark reversal in American housing dynamics. From 1950 to 1980, metros added over 50 million homes as builders responded to rising prices with increased supply. The suburbs, aided by interstate highways and permissive zoning, absorbed millions of new households and their growing families. When demand surged, construction followed—a feedback loop that defined postwar prosperity.

But after 2000, this market responsiveness disappeared. Glaeser and Gyourko document how housing growth rates continued to decline to an anemic 1.2 percent annually in the 2010s. Such uniformity signals, not market forces, but systemic barriers overriding local variation and consumer demand.

The numbers are stark. In 1970s Dallas, doubling home prices triggered a 72 percent increase in local construction. By the 2010s, the same price spike yielded just 7 percent more building.

In Phoenix, supply elasticity collapsed from 65 percent to 10 percent. As Zillow Chief Economist Dr. Skylar Olsen observed, “It seems straightforward. We need to build more homes. Changes through policies like modest densification will give us more ‘at bats’ to create density and help communities stay livable for everyone.”

The regulation trap

The culprit is not land scarcity—a persistent myth that obscures the real problem. If space were the constraint, dense urban cores would see construction slowdowns while suburban areas picked up the slack. Instead, the opposite has occurred.

By the 2010s, dense neighborhoods were adding more housing relative to their land area than suburbs. In Miami, 44 percent of new housing was built in low-density areas in the 1970s. By the 2010s, that figure had plummeted to 12 percent.

The Wharton Residential Land Use Regulatory Index, which measures local regulatory constraints, correlates strongly with housing market dysfunction. Communities with higher regulatory scores see far less construction when demand increases—not just an academic finding but an indictment of local political choices that prioritize incumbent property values over regional housing needs.

The Wharton Residential Land Use Regulatory Index, which measures local regulatory constraints, correlates strongly with housing market dysfunction. Communities with higher regulatory scores see far less construction when demand increases—not just an academic finding but an indictment of local political choices that prioritize incumbent property values over regional housing needs.

Joseph Gyourko, a leading housing economist at Wharton, has long argued that land-use regulation that limited building in some cities drives up prices by artificially capping housing supply. In highly regulated markets like New York City, prices will be determined almost solely by demand rather than construction costs.

The cost of exclusion

These regulatory barriers manifest in multiple forms: minimum lot sizes, maximum height limits, discretionary review processes, and environmental or historic preservation rules that make building slow, expensive, or impossible. Often justified as protecting “community character,” these policies systematically exclude working families, minorities and renters—anyone not already fortunate enough to own property.

The National Association of Home Builders quantifies the burden: regulatory costs account for nearly 25 percent of a single-family home’s final price and over 40 percent of a typical apartment’s cost. NAHB Chairman Buddy Hughes testified to Congress that “regulatory costs, which include complying with building codes, zoning issues, permitting roadblocks and other costly challenges,” represent the primary barrier to addressing the housing affordability crisis.

Up for Growth CEO Mike Kingsella summarized the challenge: “Restrictive and exclusionary zoning, artificial barriers, and NIMBY opposition have combined to create an unprecedented and persistent housing shortage.” The organization’s research shows a 3.79-million-unit gap in home production across 230 metropolitan areas.

Up for Growth CEO Mike Kingsella summarized the challenge: “Restrictive and exclusionary zoning, artificial barriers, and NIMBY opposition have combined to create an unprecedented and persistent housing shortage.” The organization’s research shows a 3.79-million-unit gap in home production across 230 metropolitan areas.

This regulatory strangulation extends far beyond California’s notorious restrictions. The pattern appears in red-state suburbs, Sun Belt cities, and small towns nationwide. Senior White House economist Jared Bernstein identified the core problem: “From the perspective of developers, building affordable housing just does not pencil out” because regulations create market failures where development costs exceed what middle-income families can afford.

The federal government has begun responding. Bernstein explained how infrastructure grants now incorporate housing incentives: “When we structure some of the grants and loans that we provide, we say, ‘Look, if you want an infrastructure grant, that’s great. We want to give it to you. Tell us how you’re going to free up some exclusionary zoning, and we’ll make sure you have a better chance of getting that bid.’”

The YIMBY response

Pro-housing advocates have mobilized to address these failures. California YIMBY, with over 80,000 members, has helped pass eight pro-housing bills enabling at least 1.5 million additional homes statewide. The organization’s mission reflects the stakes: “California’s housing shortage—and the affordability, environmental, equity, and health crises it has caused—is the result of decades of deliberate policies to limit the supply of housing.”

Research by the California YIMBY Education Fund found that roughly 30 percent of the state’s eight million addressable parcels could accommodate additional housing absent regulatory barriers. Yet, jurisdictions permitted fewer than 140,000 units annually between 2018 and 2021—less than 1 percent of market-feasible opportunities.

The solution requires coordinated action across all levels of government. Following California, Oregon, and Washington in allowing duplexes, triplexes, and accessory dwelling units by right would continue to reverse the housing doom loop in which the nation has found itself. Federal leadership tying transportation funding to zoning reform and establishing stronger national housing equity standards would also revitalize the path back to a stronger and mobile middle class.

As U.S. Chamber of Commerce President Suzanne Clark and former White House National Economic Council Director Brian Deese argued in the Wall Street Journal, “For decades, exclusionary zoning laws—like minimum lot sizes, mandatory parking requirements and prohibitions on multifamily housing—have inflated costs and locked families out of areas with more opportunities.”

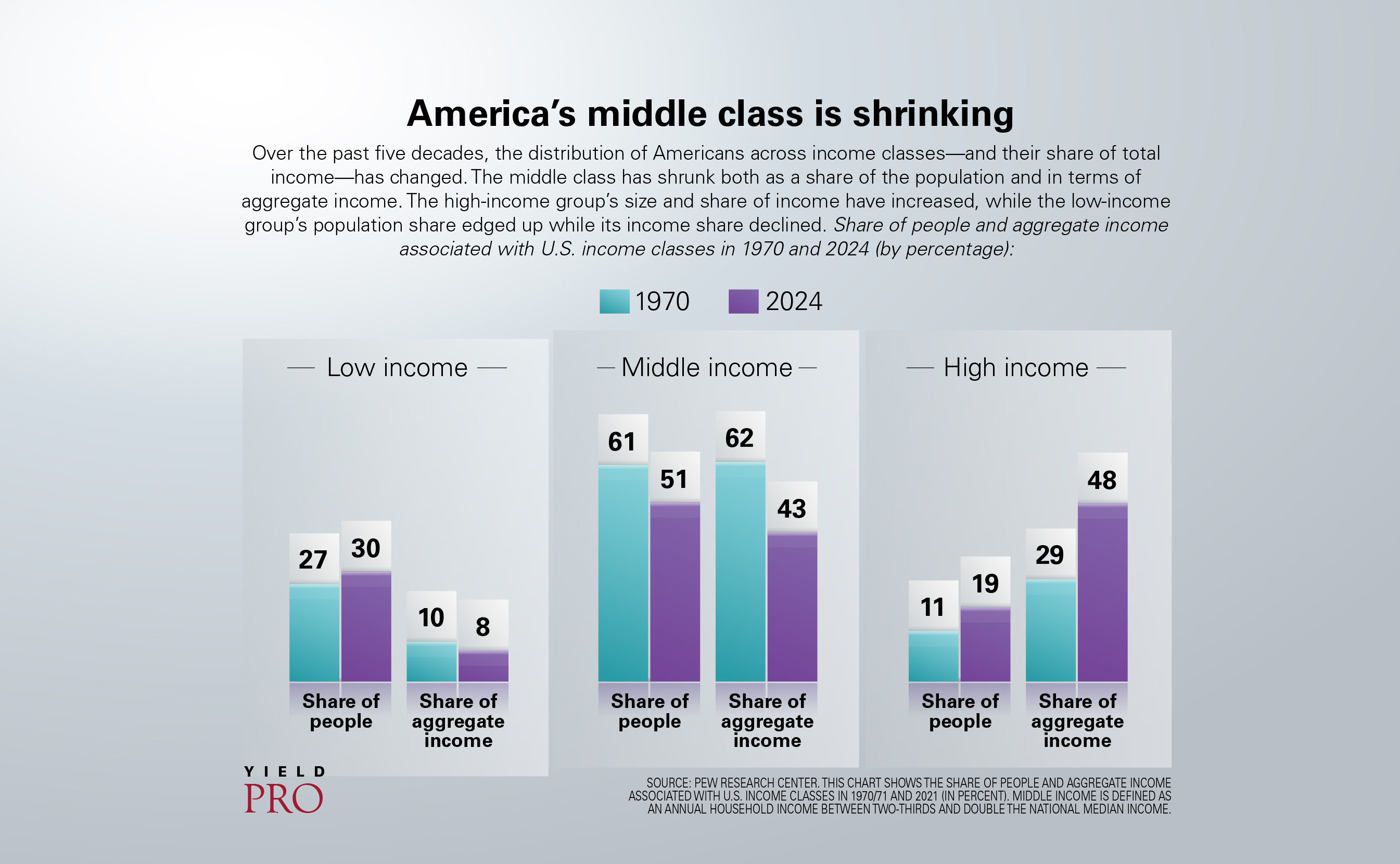

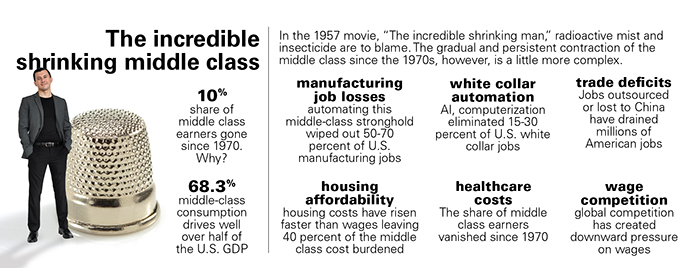

The stakes extend beyond housing. Research suggests that housing misallocation costs up to 2 percent of GDP (Brookings)—more than $400 billion annually in lost economic output. In the words of National Association of Realtors Chief Economist Lawrence Yun, “The losers are clearly the rising rental population that can’t participate in this housing equity appreciation. They are missing out on [a big] source of middle-class wealth.”

Reopening the suburban frontier

Fifteen million missing homes represent more than a housing shortage—they embody a broken promise to generations of Americans seeking economic mobility. The suburban frontier that once provided escape from high-cost coastal cities has been systematically closed by local regulations prioritizing preservation over opportunity.

Reopening this frontier requires not paving over every field but allowing neighborhoods to evolve, welcome new residents, and build homes that reflect 21st-century demographic realities. The alternative—rationing the American Dream by ZIP code—contradicts the nation’s founding principles of opportunity and upward mobility.

As Glaeser and Gyourko conclude, America’s housing markets no longer respond to demand. Restoring that responsiveness—through zoning reform, permitting streamlining, and federal leadership—represents perhaps the most pressing domestic policy challenge of our time. The costs of inaction compound daily in rising rents, longer commutes, and diminished prospects for an entire generation locked out of homeownership.

As Glaeser and Gyourko conclude, America’s housing markets no longer respond to demand. Restoring that responsiveness—through zoning reform, permitting streamlining, and federal leadership—represents perhaps the most pressing domestic policy challenge of our time. The costs of inaction compound daily in rising rents, longer commutes, and diminished prospects for an entire generation locked out of homeownership.

The time for incremental reform has passed. America needs bold action to rebuild the housing abundance that once defined the nation’s promise to working families. Only then can we restore the suburban frontier as a pathway to middle-class prosperity rather than a barrier to it.